A Double-Edged Sword: The Role of Social Media in the 2024 Political Uprising in Bangladesh

Parama Sigurdsen, Ravi Iyer / Sep 30, 2024When I worked at Meta, some of the most important things I learned were from the global experiences of people engaging with social media during conflict. Social media makes activism easier – whether that means raising funds for a local cause, sharing about dangers that people are unaware of, or protesting an injustice, whether it be a new regulation or an unfair election. Companies have policy teams that work hard to figure out the difference between “good” activists (e.g. those protesting recent illegitimate elections in Venezuela or fighting authoritarian governments) vs. “bad” activists (e.g. those seeking to undermine legitimate American elections with violence in 2020 or fighting scientifically grounded COVID policies by spreading false claims).

I put “good” and “bad” in quotes not because I don’t have an opinion about these, but rather because it is an inherently dangerous exercise to give any company or government the power to decide which activists are good or bad. India, for example, has used this precedent to stifle dissent in ways that alarm many civil society groups. This realization is behind the Neely Center’s focus on design, where we ask what online forces bend activism in a better or worse direction, and what platform design choices should be made accordingly. Maybe activism is meant to be hard, and it is the difficulty of it that enables more just activism to triumph over activism that relies on faulty information, targets minority groups, or that benefits activist leaders rather than the broader community.

It is with this lens that I want to introduce you to Parama Sigurdsen, our research program manager at the USC Neely Center, who is an indispensable part of our team. She also happens to be from Bangladesh and was kind enough to share the below experience of her social media feed during recent protests, which features both good and bad forms of activism. I often come away from reading about such experiences even more aware of the lack of context that I (and most tech workers and policy makers) have in making content moderation decisions in such contexts.

-Ravi Iyer

A Double-Edged Sword: The Role of Social Media in the 2024 Political Uprising in Bangladesh

Parama Sigurdsen is the Research Program Manager at the Neely Center for Ethical Leadership and Decision-Making at the USC Marshall School of Business.

July 10, 2024. Dhaka, Bangladesh. Students protest near Dhaka University. Shutterstock

2024 will undoubtedly be remembered as a year of significant change around the world. A number of countries went to the polls this year, some went to war, and others took to the streets in pursuit of a better future. Bangladesh, my country of birth, is in the latter category. Recently, the people rose up in protest against an unpopular and questionably elected regime and toppled it, driven by a deep desire for change. Yet, it seems that not much thought was given to what this 'change' should actually look like. Technology and social media platforms have played a crucial role in this unfolding drama. For better or worse, digital media has allowed me to witness firsthand how news—both true and false—and ideas—both constructive and destructive—spread across social platforms, shaping the destiny of a nation in real-time.

To give a bit of context, Bangladesh is a small country—about 56,000 square miles, roughly the size of Iowa—with an extremely dense population of 117 million, a little over a third of that of the United States. Nestled in the western curve of India, Bangladesh shares most of its land border with this larger neighbor, with a small stretch adjoining Burma (a.k.a Myanmar). To the south, it meets the Bay of Bengal. The population is largely homogenous: nearly everyone speaks Bangla (Bengali) as their first language, and over 90% are Muslim. Yet, despite this apparent homogeneity, the nation has never enjoyed a sustained period of calm in its 53 years of existence.

The Evolution of Technology and Social Media in Bangladesh

Bangladesh has undergone significant changes in technology adoption over the past few decades. The use of technology was the domain of the affluent until fairly recently. In 1990, internet and cell phone use was nearly nonexistent in Bangladesh. Then, in the late 2000s, a boom happened. By 2020, internet usage jumped to 39%, and the number of cell phones in the country exceeded the population. The modest use of the internet in 1990 was not far from the global baseline, but cellphone use going from 0 to 100 was a major leap. Transmitting a message to the wider world, which was a significant challenge two decades ago, has now become routine. Moreover, the expectation to have access to do so is now a given.

In mid-July this year, I first started noticing sporadic posts on group chats and Facebook about student protests heating up in the country. Police were shooting at the students. At first, I wasn’t concerned; those who grew up in Bangladesh in the 90s would know that students clashing with the police is often seen as “a feature not a bug” of campus life. Higher education came with an implicit understanding that as part of earning a degree in the country’s elite universities, students will, from time to time, sniff tear gas, dodge bullets, and run from the clashes taking place on the campus ground, whether it is students against the police or between opposing student groups. But this was different. It persisted for one week, then two.

The Spark: Protests and the Power of Social Media

I began to worry when friends and family started sending videos of the uprising. The clips were chilling and deeply unsettling. This was not the usual campus skirmish I remember from my student days. I started paying close attention. The protesters started off by demanding the removal of job quotas reserved for different population categories: 56% of government jobs were carved out under the quota rule, with only 44% of jobs open to merit-based competition. The lion's share of the reserved jobs (30%) were for the descendants of war veterans who fought in the 1971 War of Independence, with smaller quotas allocated to disadvantaged groups: women (10%), marginalized districts (10%), ethnic minorities (5%), and people with disabilities (1%). The demands the students were making were not unreasonable. In an intensely competitive employment market, one could see why this would cause deep frustration among the youth.

From my vantage point, social media transformed the student protests into a national movement. I could see videos, photos, and posts from the ground inundating my group chats, Facebook, Messenger, and WhatsApp. Many looked like they were uploaded by protesters in real-time. The images were raw, unfiltered, and profoundly unsettling, and resonated deeply with people, sparking outrage and solidarity across the country and beyond.

One of the most powerful effects of social media was how efficiently it galvanized support for the students from more than 7 million Bangladeshis living abroad. Within days, the protests had expanded from a student movement to a nationwide uprising. One could see oceans of people standing up to the armed law enforcement officers. The scenes were both powerful and symbolic—David against Goliath, only this time there were hundreds of thousands of Davids staring down Goliath. Yet, beneath the surface, not everything was as it seemed.

A close friend called to tell me she was scared. She wrote, “The hashtag #IAmRazakar is trending. This isn’t right.” To provide context, the 'Razakars' were a group considered traitors during the 1971 War of Liberation for collaborating with the Pakistani military. They played an active role in the genocide that ensued over the nine months of war, with Hindus—a religious minority in Bangladesh—being one of their prime targets. The absurdity could be illustrated by a European equivalent: imagine if thousands proclaimed “I am Quisling” in Norway after WW2. This should not be the call to arms for a nation rising against tyranny. Something somewhere has gone terribly wrong.

I learned soon that #IAmRazakar was a reaction to an off-handed comment by the Prime Minister. She had implied that if the descendants of war veterans were denied their quotas, would those positions then go to the descendants of the Razakars—those who had collaborated with the enemy? Her statement spread like fire country-wide and riled up the protesters even more. In a bitter twist of irony, through the power of hashtag, the term “Razakar,” long associated with treachery, got co-opted and diluted in a way that was perhaps unintended but deeply unsettling. What should have remained a term of derision is now being reclaimed in a socio-politically acceptable manner, a sign that somewhere along the way, the narrative had veered dangerously off course.

The Government's Response: Internet Shutdowns and Escalating Tensions

As the protests grew in intensity, the Bangladeshi government responded with increasing severity. Over 100 deaths of protesters at the hands of law enforcement, some caught on video, made the rounds on social media, as did the footage of rampant destruction of property by the protesters. The situation reached a tipping point when several state-run institutions’ websites were hacked, prompting the government to take the drastic step of shutting down the internet nationwide.

The government’s rationale was clear: by cutting off access to social media, they hoped to disrupt the protesters’ ability to organize and communicate. But this move backfired spectacularly. Instead of quelling the unrest, the internet blackout only intensified the anger. It was perceived as a desperate attempt by the government to silence the people, and it served to further galvanize the protesters. The blackout became a symbol of the government’s disconnect from its citizens and its willingness to go to extreme lengths to cling to power.

Despite the internet shutdown, the flow of information was not entirely halted. While communication was undoubtedly hampered, the protesters proved resourceful, finding creative ways to bypass the restrictions. They turned to VPNs, satellite communications, and other tools to stay connected with each other and the world beyond Bangladesh's borders. The government’s attempt to stifle dissent had not only failed but had inadvertently strengthened the resolve of the movement.

Fear and Division: The Rise of Sectarian Tensions

Under the persistent pressure of nationwide protests, the government finally relented: after 10 long days, internet access was restored. On July 21, 2024, the Bangladesh Supreme Court overturned the majority of the job quotas, declaring that 93% of government jobs would now be open to merit-based competition, leaving only 7% reserved for disadvantaged groups. This could have been the movement’s endpoint—a moment to celebrate and begin the work of rebuilding. And for a brief time, it was. But victory wasn’t enough anymore. The government had acquiesced but the white flag was waved too late. The movement continued, now with a new goal: to topple the regime entirely. The government responded with a nationwide curfew, which only served to stoke the fires of rage further.

At this critical juncture, a new and more troubling dynamic began to emerge. Up until this point, the movement had been largely organic and non-partisan. It was driven by a collective desire for justice, cutting across political lines. But just as a return to normalcy seemed within reach, the protest took on a political tilt. Social media posts and messages, which had been crucial in uniting protesters, now began to carry the weight of political agendas. Various political groups started joining the protests, gradually edging their way to the forefront. The march continued, only this time, with a side order of sectarian violence.

When the Wi-Fi returned, my initial relief at learning that my loved ones were safe was quickly overshadowed by a growing sense of dread. My Hindu friends were terrified. The hashtag #IAmRazakar had come home to roost in the most horrifying way. Hindu temples, businesses, and homes were being raided, ransacked, and set on fire. My friend, who has two teenage daughters, was too scared to leave her house, yet didn’t feel safe staying indoors either. Her voice broke with tears as she described the desecration of sculptures, national monuments, and public art throughout the city. She sent me gut-wrenching videos of the mindless destruction and arson happening across the country. Her anxiety for her mother and siblings, who lived on the other side of the city, was palpable. Traveling to them was out of the question, and she couldn’t ask them to come to her for the same reason. Another Hindu friend sounded defeated when I called to check in on him. “At least you asked; no one else has,” he said quietly. The moment of victory had transformed into a nightmare, where fear and hate tore apart the dream for justice the movement had sought.

The Role of Social Media in Spreading Disinformation

In early August, the government finally crumbled. The Prime Minister resigned and fled into exile, leaving the armed forces to assume control of the country. After over 300 deaths and billions of dollars in damages, the student movement had achieved a resounding success. Social media buzzed with hashtags like #VictoryForBangladesh and #BangladeshRising, as celebratory posts flooded my timelines with superlatives like “This is our true Independence Day” and “This victory is greater than the victory of 1971.” But for my Hindu friends, who had supported the cause from the very beginning, this was a deeply disheartening time. Once again, like a recurring nightmare, they found themselves targeted simply because of their religious identity.

As reports of violence against religious minorities surfaced, so did the denial of these events, with both sides leveraging social media to establish their version of the “truth.” Religious fundamentalists, who had been largely absent in the early stages of the protests, began to insert themselves into the movement. They seized upon the unrest and the hashtag #IAmRazakar as opportunities to push their agenda back onto the national stage. Emboldened by their newfound legitimacy, they incited violence against minorities. Hashtags like #HindusSafeInBangladesh started trending, often accompanied by posts claiming that the reports of violence against Hindus were exaggerated or outright fabricated. But for those living through it, the reality was starkly different. My Hindu friends lived in constant fear, unsure if they would be the next targets. The use of social media to deny their experiences was not only deeply hurtful but also dangerous, as it obscured the true nature of the crisis from the international community.

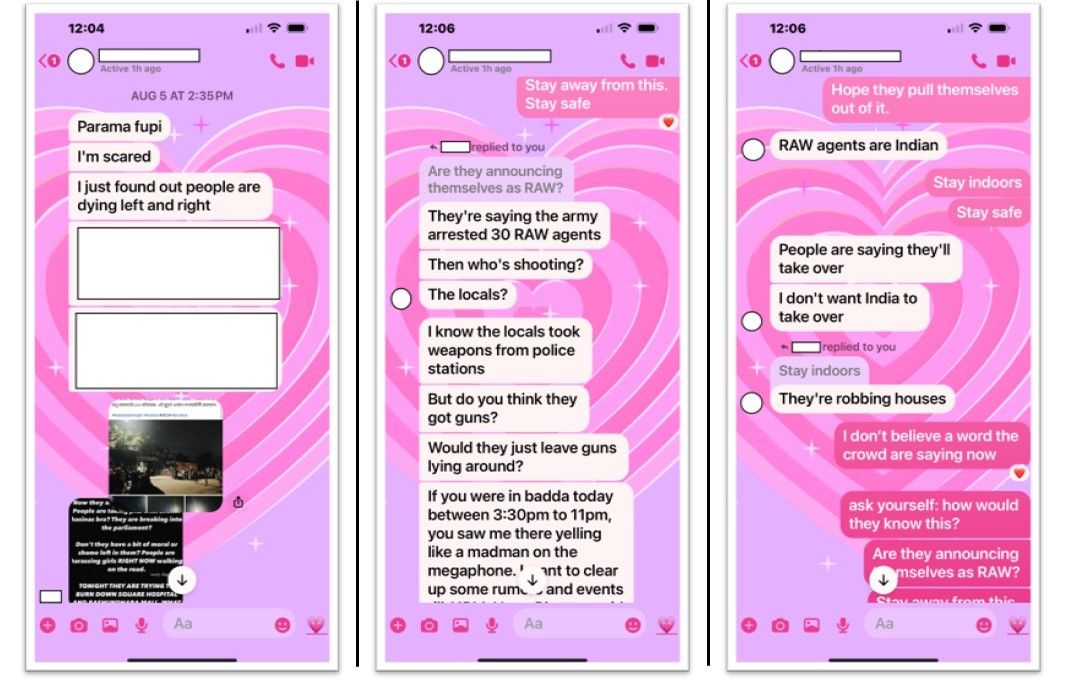

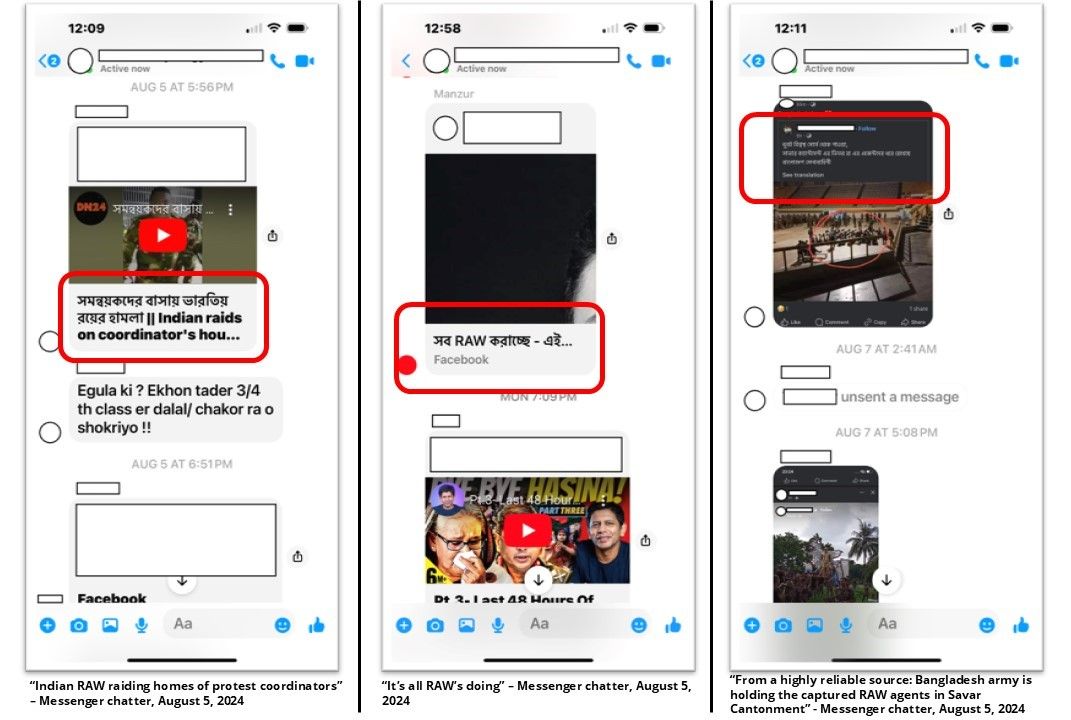

One of the most insidious aspects of the disinformation campaign in the final days of the movement was how it preyed on existing prejudices and fears. Rumors falsely claiming that Indian agents were attacking Muslim protesters (see examples below) were shared without verification, fueling suspicion and hostility. This made it easier for those with vested interests to argue that even if the reports of sectarian violence against Hindus were true, they were somehow justified.

Screenshots of an anxious girl's account spreading unverified rumors on the night of August 5, 2024. Provided by Parama Sigurdsen.

Messenger screenshots that show rumors falsely claiming that Indian agents were attacking Muslim protesters during the protests. Provided by Parama Sigurdsen.

The spread of disinformation through social media during the protests was a deeply troubling development. Social media platforms are just tools; their impact, whether for good or bad, depends entirely on how they are used. They can be powerful vehicles for spreading the truth and rallying support, but they can also be used to sow confusion and manipulate public opinion. False reports of violence, doctored images, and misleading videos circulated widely, making it increasingly difficult for people to discern what was true.

The ability of social media to amplify both truth and lies made it a double-edged sword in the context of the Bangladesh protests. On one hand, it gave ordinary people a voice and helped build a global movement for change. On the other hand, it provided a platform for those with little interest in the core cause to gain legitimacy, undermine civic responsibilities, and spread fear, division, and misinformation. This dual nature of social media technology highlights the complex and often contradictory role it plays in shaping modern political and social movements. This erosion of trust in information sources leads to a loss of faith in our institutions and in each other.

The Globalization of Protest: Social Media and the Diaspora

As with many other Bangladeshis living abroad, social media became my primary source of information about the unfolding events back home. Traditional news outlets simply couldn't keep pace with the rapid flow of updates on platforms like Facebook, WhatsApp, and Messenger. The diaspora played a crucial role in amplifying the voices of the protesters. Videos of police brutality, stories of resistance, and urgent calls for international support spread like wildfire through expatriate communities, creating a global network of solidarity for the movement.

This globalization of protest was one of the most remarkable aspects of the 2024 uprising. Social media facilitated real-time communication and coordination between protesters in Dhaka and their supporters in cities around the world. Hashtags like #BangladeshRising and #SupportBangladeshProtest began to trend globally, drawing international attention to the situation in Bangladesh and rallying support from every corner of the globe.

Conclusion: The Double-Edged Sword of Social Media

The 2024 political uprising in Bangladesh will undoubtedly be remembered as a pivotal moment in the country’s history. It was a time when the people rose up to demand change, fueled by a deep-seated desire for justice. Social media played a central role in this movement, amplifying the voices of students and ordinary citizens alike, while also helping to build a global network of support.

Yet, the movement also exposed the darker side of social media. These platforms, which have the power to spread truth and mobilize support, can just as easily be weaponized to spread lies, sow division, and manipulate public opinion. The rise of disinformation, the involvement of extremist elements, and the use of social media to deny and obscure the truth all served to complicate the narrative of the protests and to undermine the legitimacy of the movement.

The dust of the uprising has yet to settle, and the future path for Bangladesh remains uncertain. Will the hashtag #VictoryForBangladesh truly signify a victory for all its citizens? Can the nation rise from the ashes of charred temples and broken sculptures that lie in the wake of the movement? Or is it at risk of descending into lawlessness and becoming a failed state? Whatever direction the country takes, I imagine that social media will continue to play a central role in shaping Bangladesh’s journey forward. The lessons of 2024 will be crucial in guiding this effort, as the nation grapples with the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead.

Authors