AI, Surveillance, and Suspicion: Listen To Warnings From the Black Community

Nakeema Stefflbauer / Feb 7, 2024

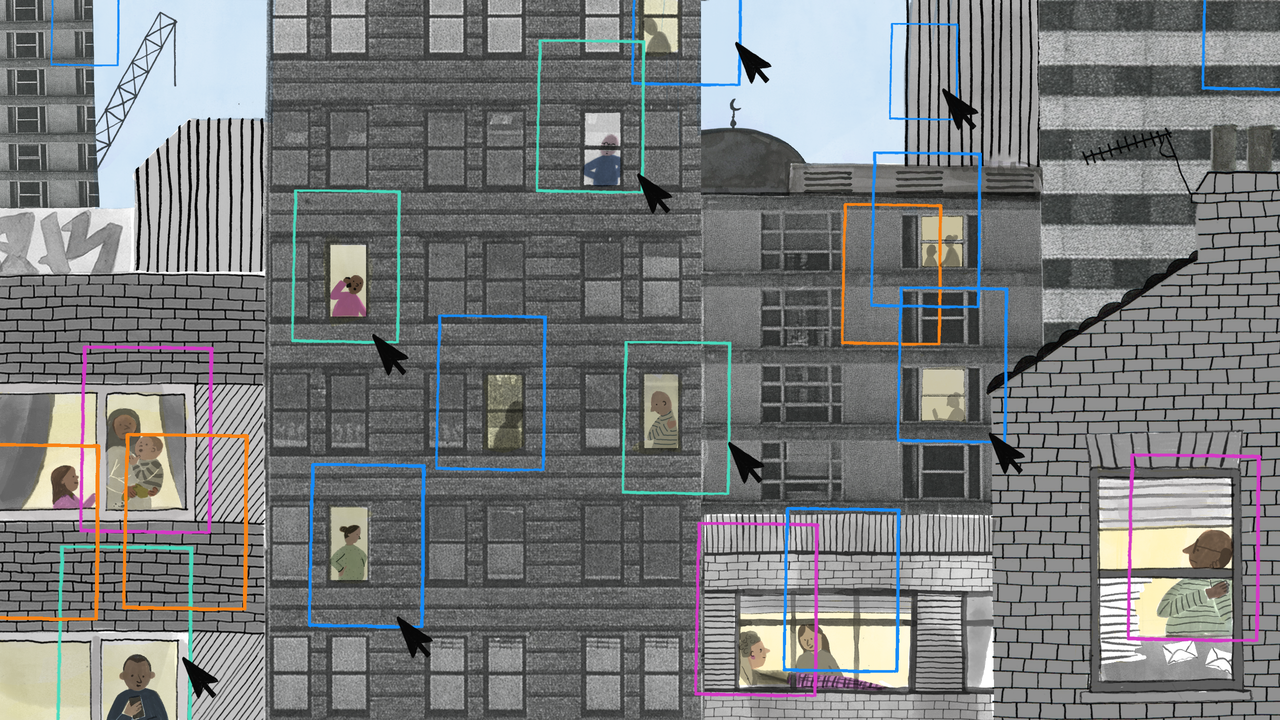

Emily Rand & LOTI / Better Images of AI / AI City / CC-BY 4.0

Since I was a kid growing up in Brooklyn, New York, the experience of being spied on has been a source of personal rage. Almost every Black person in America knows the feeling of being followed in public. I moved abroad over a decade ago to escape from constant surveillance based on race. These days, I am outspoken about the ways that technology can be a force for good. The non-profit organization that I founded in Berlin, Germany, FrauenLoop, introduces women with immigrant and refugee status to computer programming.

But after years of working with these individuals, I know that many of my students must take special care to avoid the potential tracking of their online activities. Spying, surveillance, and stalking—these are legitimate concerns that stay with my students even after they escape the realm of oppressive, intrusive government regimes. I have my own experience from growing up Black in America, but I’ve learned more about the potential threat of surveillance from working with my students and from my other experiences abroad.

For instance, living in Damascus, Syria, while researching my dissertation on black-market trade, I witnessed, first-hand, the realities of authoritarian surveillance states. In Syria, US “passport privilege” protected me from being snatched off the street by the mukhabarat, or secret police. But for some of my students, this fear remains at the fore. If anything, suspicion of algorithms based on fear that the government may be watching is typical for many people living outside of Western countries.

Understanding these fears has made me all the more concerned about the lack of public protest over unregulated adoption of “AI” technologies in the United States and other Western countries. It’s not hard to imagine dystopian outcomes when the status quo involves a massive (and growing) digital dragnet. When AI-powered surveillance technology is sold to schools to predict who’s cheating, to employers to track whose expressions appear interested during meetings, and to law enforcement to predict whose face most resembles CCTV video of a criminal, it is worse than old-school, in-person harassment that you could at least see and question. When you’re required to scan your face instead of your boarding card at a US airport, this isn’t for your convenience. Those unmanned drones marketed as home delivery hovercraft? Only convenient until they capture unauthorized photos or video of your home (or of you). Inevitably, captured content gets re-purposed for entirely different uses, such as crime investigations.

Every day, there are new stories of AI gone awry. Key applications of machine learning and artificial intelligence, like computer vision, rely on mass data collection. In Argentina, a man was jailed for days after facial recognition software identified him as the perpetrator of crimes he didn’t commit. AI software for automated plagiarism-detection has falsely accused students in New Zealand of using AI to cheat on assignments. However modern voice-activated speakers may appear, around-the-clock data collection is often their underlying function. Let’s be clear: 24/7 surveillance is what happens when you’re in jail, or in what Georgetown Law School’s Center on Privacy & Technology has termed “the perpetual line-up.”

And yet, in a tech industry that has historically failed at diversity, there are always people who view “AI” for gait recognition, voice recognition, and so-called “emotion recognition” as innovative tech that someone will eventually build somewhere —so why not here and now? When the designers of these technologies have little or no experience of being under surveillance or encountering state violence, they are incapable of recognizing the dangers in what they build.

This is why I have devoted my career to creating pathways for individuals from diverse backgrounds into tech careers. It makes sense to me that some of the most vocal critics of today’s technology industry generally and AI specifically are Black women such as Dr. Joy Buolamwini, Dr. Timnit Gebru, Dr. Abeba Birhane and Deb Raji. We need more people who have experienced oppression at the table in tech companies if we are ever going to create a technology industry that is not rooted in surveillance.

But diversity alone will not be enough. In the US and elsewhere, we have to demand legislation that protects us from “AI” used as a tool of mass surveillance. That’s why we should insist that our lawmakers do more than meet with “AI” company founders and ignore whom they sell their products to and/or how poorly the “AI” might work.

Failure to build a technology industry that protects us from state oppression and unlawful surveillance is bad, but worse is facing AI surveillance that is often invisible. Local initiatives such as the S.T.O.P. Surveillance Technology Oversight Project in New York have supported the passing of Community Control of Police Surveillance (CCOPS) laws that are in effect in eighteen communities across the US. These community ordinances and broader bans, like those in Massachusetts and San Francisco forbid the use of “AI” facial recognition software by government agencies. This is a good start but, while such provisions are limited to specific jurisdictions, the risk remains that “AI” technologies can still be used to surveil some or all of us in public.

The rush to deploy “AI” applications worldwide has already led UK schools, Dutch social services agencies and US employers to be accused of discrimination for subjecting the public to what amounts to profiling. But, whether it’s race-based, age-based, or connected to the neighborhood you live in, profiling is best known as a police approach to identifying wrongdoers. Do any of us deserve a future where we face constant algorithmic profiling, also known as surveillance, wherever we go? In a world where AI surveillance is rapidly becoming ubiquitous, there will be nowhere to escape to. In that world, the irony of our increasing reliance on “AI” technologies may be that soon, everyone will develop some understanding of how it feels to live in America while Black.

Authors