Artificial Intelligence as a Tool of Repression

Justin Hendrix / Oct 4, 2023Audio of this conversation is available via your favorite podcast service.

Every year, the think tank Freedom House conducts an in-depth look at digital rights across the globe, employing over 80 analysts to report on and score the trajectory of countries on indicators including obstacles to access, limits on content, and violations of user rights.. This year’s iteration is headlined Advances in Artificial Intelligence Are Amplifying a Crisis for Human Rights Online.

Once again this year, I spoke to two of the report’s main authors:

- Allie Funk, Research Director for Technology and Democracy at Freedom House, and

- Kian Vesteinsson, Senior Research Analyst for Technology and Democracy.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of the discussion.

Allie Funk:

My name is Allie Funk, I'm research director for technology and democracy at Freedom House and, luckily, a co-author of this year's Freedom on the Net report.

Kian Vesteinsson:

Great to be here with you, Justin. My name's Kian Vesteinsson, I'm a senior researcher for technology and democracy at Freedom House and also a co-author of this year's report.

Justin Hendrix:

This is the second year I've had you all on the podcast to talk about this report, which has been going now for 13 years, lucky 13, but unfortunately, it's not good news. We've got the 13th consecutive year that you report of declines in internet freedom.

Allie Funk:

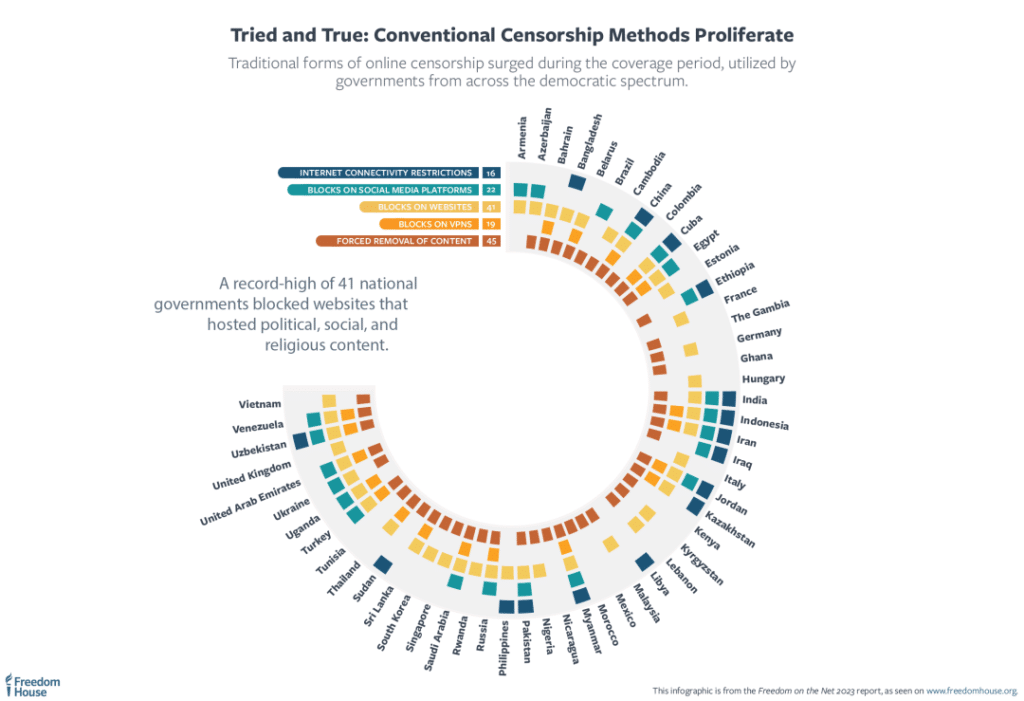

I keep saying I've been doing this report for six years, one of these years, I can't wait to say that internet freedom improved for the first year and we can have a beautiful positive essay, but this year is not the year, which I don't think will be surprising for a lot of your listeners. Global internet freedom, yeah, the decline for the 13th consecutive year and we actually found that attacks on free expression have grown more common around the world, so we have two record-high assaults on free expression, one around folks who faced arrest for simply expressing themselves, we had more at least 55 different countries in which that was happening, and then also a record high in the number of governments, so 41, that blocked political, social, and religious content.

We dive into that in the report, we also highlight the ways in which artificial intelligence is deepening this crisis for internet freedom, zooming in here on disinformation campaigns and censorship, and we close the report really calling for the need to regulate AI, because we do think AI can be used for good when it is regulated appropriately and used appropriately, but also, closing with the democracy, communities need to learn the lessons of the past decade of internet governance challenges to apply to AI and also to not lose momentum in protecting internet freedom more broadly.

Kian Vesteinsson:

That is the headline on this year's report, "The Repressive Power of Artificial Intelligence." Let's talk a little bit about that focus. Clearly, that's the hot topic of the moment, folks are concerned about generative AI, other forms of artificial intelligence that may be used as tools of repression, tools of censorship in particular. I happen to be at the Stanford Internet Observatories Trust and Safety Research Conference while we're recording this, there's a lot of discussion here, of course, about generative AI and about artificial intelligence more generally, and how it will be deployed across the internet in various content moderation efforts. There's one way of thinking about that that is positive, that perhaps we can help ameliorate problems like hate speech, harassment, and child sexual abuse, et cetera. On the other hand, you've got authoritarians who want to use these tools for very different purposes, indeed.

Allie Funk:

Absolutely. There is a lot of benefit in the use of automated systems within content moderation, and I'm sure that is one of the conversations at the conference. The type of material that human moderators have to review is so graphic and traumatizing, so there's a way here that automated systems can help ease that and they're also really necessary to detect influence operations, but one of the few things that we dived in on AI is, first, if you want to make the point that... AI has, for many years, been exacerbating digital oppression, especially as it relates to surveillance, and that's not something we zoomed in on this year's report, but I think it's really important to say that upfront. As we looked at generative AI and the ways in which it's going to impact information integrity, we think about it as there are longstanding networks of pro-government commentators around the world, so in the 70 countries we cover, we found that at least 47 governments deployed folks to do this. That can be hiring external, shady public relations firms to do that work, it might mean working with social media influencers.

Kyrgyzstan hires high schoolers to do this, which is super interesting to me, I guess Gen Z is really great at knowing what's going on online. My millennial self, not always that case. These networks have existed for a really long time. We view gen AI as these networks will increase their reliance on these tools and, what it does, it lowers the barrier to create disinformation and then these existing networks will then be able to disseminate it at scale. It's really about that creation part and we found 16 different examples in countries where gen AI was already used to distort political and social-religious content, so we already see it happening, but we expect it's going to get a lot worse in the coming years.

Justin Hendrix:

Give me a few more examples of some of those 16 countries. What are you seeing with regard to the use of generative AI?

Kian Vesteinsson:

I think it's really important to set the stage here and acknowledging that we found 16 examples of this, but there are likely more. It's very hard to identify when content has been generated by one of these AI tools. The lack of watermarking practices within the market is especially exacerbating this when it comes to images and other media content. Of course, telling the difference between text that's been written by a human being and text that's been generated by ChatGPT or another AI chatbot is becoming increasingly difficult. We expect that this is an under count and that's just the limitation of the research that's possible into this. Now, let's talk about examples. In Nigeria, there were really consequential elections in February 2023. The current leader was term-limited, so the elections were very highly contested. We found that an AI-manipulated audio clip spread on social media allegedly showing the opposition presidential candidate talking about plans to rig the balloting and this content really threatened to inflame a sensitive situation to fuel partisan animosity and longstanding doubts about election integrity in a country that's seen really tragic election-related violence in the past.

Then there's Pakistan. This is an incredibly volatile political environment, the country has seen a yearlong plus political crisis stemming from former prime minister, Imran Khan's, feud with the military establishment. That crisis has seen Imran Khan arrested multiple times, violent protests breaking out in response, and all sorts of really brutal repression targeting the supporters of Imran Khan. Imran, in May of this year, posted a video clip on social media that featured AI generated imagery of women standing up to the military in his favor. This sort of content really degrades the information environment in really volatile times, and quite frankly, the people need to be able to trust the images that they're seeing from political leaders in times of crisis like this.

One final example for you. Ahead of the Brazilian presidential runoff in October 2022, a deepfake video circulated online and this video falsely depicted a trusted news outlet showing that then President Bolsonaro was leading in the polls. Again, this is information that is masquerading as coming from a trusted source, one that people may be inclined to believe, and videos like these have the potential to contribute to a decaying information space and have a very real impact on human rights and democracy.

Justin Hendrix:

You point out that one of the things we're seeing, of course, is a commercial market for political manipulation and, in some cases, the use of generative AI tools in order to do that manipulation, and appears, I suppose, based on prior reports, Israel's emerging as one of the homes to this marketplace.

Allie Funk:

It's not just with regards to disinformation, too. I think this is what's really interesting about digital oppression more broadly, the ways in which the private sector bolsters those efforts and, because of booming markets for these repressive tools, it's lowered the barrier of entry for digital oppression generally, so this relates to surveillance and the spyware market, which I think has gotten a lot of really important attention and that's where companies from Israel are really thriving. That, in part, has to do with the relationship between the Israeli state and the security forces and the private sector and the ways in which learning across those sectors occurs, but we're seeing increasingly, also, the disinformation market and the rise of these really shady public relation firms. We highlight, "Israel is home to a lot of these," within the report. There was this fantastic reporting from Forbidden Stories and a few others that... Just wonderful work of journalists going undercover to unravel what is called "Team Jorge" and the ways in which this group of folks in this company really have been able to bombard the information space and sell their services to governments.

One of the really concerning examples that we highlight is the ways in which Team Jorge was working with somebody in Mexico, it's always hard to get attribution here, and they used fake accounts and manipulated information to really orchestrate a false narrative around these really serious allegations of a Mexican official and his involvement within human rights abuses, fabricating evidence and criminal campaigns. A really tangible example there. Interesting enough, a lot of these companies are also popping out from the UK and other democracies as well, which speaks to the opportunity for democracies to really respond and try to clamp down on these sectors, especially in the spyware market, the way entity lists and export controls can play a role here.

Kian Vesteinsson:

I think one dynamic that's really important to talk about here... We talk a lot about dual-use technologies when we're talking about spyware and surveillance products. "Dual-use" here referring to technologies that may have appropriate uses that are not rights abusive and that can then be leveraged for military and law enforcement uses in really problematic ways. It's really important to acknowledge that a lot of the private sector disinformation, content manipulation trends that we're seeing are driven by companies that create completely innocuous products that may have completely legitimate uses. Team Jorge is an example on the far end of the spectrum. These are incredibly shady political fixers who are doing really dangerous stuff, but then there are companies like Synthesia, this UK-based generative AI company that creates AI-generated avatars that can read a script in a somewhat realistic way. Obviously, there's lots of completely legitimate uses for this. You could imagine it being deployed for spicing up a company compliance training or something along these lines, but we've seen products generated by Synthesia leveraged for disinformation.

Prominently, in early 2023, Venezuelan state media outlets used social media to post videos produced by Synthesia that featured pro-government talking points about the state of the Venezuelan economy, which is in free fall. The economy is having incredibly devastating effects on people's ability to survive, so having a somewhat plausible looking set of avatars masquerading as an international news outlet talking about how good the Venezuelan economy is could meaningfully shape people's perceptions of what's going on. These products that may be relatively innocuous can have really pernicious effects and that's really one lesson that regulators need to be taking away from all of this.

Generative AI, AI generally grabs the headline in this report, but of course, you've already mentioned that more conventional censorship methods are on the rise as well. Let's talk a little bit about that, the record high you've already mentioned, the 41 national governments that have blocked websites, various other tactics that you look at here. From blocks on VPNs, forced removals of content, entire bans on social media platforms.

Allie Funk:

AI does take the big framing here, but I think the research was extremely clear in the ways in which AI is impacting censorship, but also how AI is not replacing these conventional forms of censorship. I think there's a couple of different reasons why that's the case. One specific one that is on my mind a lot is that AI just isn't always the most effective in certain conditions. For instance, when there's these massive outpourings of dissent around protests, really sophisticated AI-empowered censorship or filtering tools, they can't keep up. They can't. You see that in Iran and even China. We continually will have governments, we think, resort to very traditional tactics of censorship, which I think is why it's so important that we don't always just get distracted by AI or only focus on AI.

Kian Vesteinsson:

It's a lot easier to lock up protestors than to give instructions to social media platforms about how they need to shape their content moderation algorithms to respond to crises that are breaking out live. We saw this certainly in China. It's, of course, worth noting here that China confirmed its status as the world's worst environment for internet freedom, that's now for the ninth year running, though Myanmar did come close to surpassing China and is now the world's second-worst environment for internet freedom. In China, we saw the Chinese people show inspiring resilience over the past year. As I'm sure listeners of your show will recall, in November 2022, protests over a terrible fire in Xinjiang grew into one of the most open challenges to the CCP in decades. People across the country were mobilizing against China's harsh zero-COVID policy, and this included a lot of folks who took to the internet to express dissent in ways that many may not have been comfortable doing before the protests.

Many people took to VPNs to hop the great firewall and express information about what was going on in China on international platforms, like Twitter and Instagram, that are usually restricted in China. The big story here is that, in the immediate aftermath of the protest, information about people protesting spread online on Chinese social media platforms, censors were not able to respond to the scale of the content that was being posted, and in part because Chinese internet users were using clever terms and masked references to the protest to express their descent. Now, unfortunately, the censors caught up, they scrubbed away criticism of the zero-COVID policy, imposed even harsher restraints over social media platforms in the country, and started cracking down even more heavily on access to VPNs. This mass movement of protesters did push the government to make a very rare withdrawal of its policy at a nationwide level. Conditions in China still remain very dire, censorship and surveillance are imposed in mass and systematically, but the Chinese people have found these narrow ways to express their dissent and challenge the government's line.

Justin Hendrix:

Let's briefly touch on Iran as well, which is another country that has seen, of course, a year of mass protests. How has Iran fared in this year's measurement?

Kian Vesteinsson:

I was thinking about it this morning, Justin. I think a year ago, we were here talking about the protests in Iran and what it meant for protestors to have access to all sorts of censorship circumvention tools to raise their voices online at a real critical time, and that remains the case, but unfortunately, Iran saw the sharpest decline in internet freedom over the past year in our reporting. The death in custody of Jina Mahsa Amini sparked nationwide protests back in September of last year that continued over the ensuing months. In response, the regime restricted internet connectivity, blocked WhatsApp and Instagram, and arrested people on mass.

Now, again, protestors still took creative measures to coordinate safely using digital tools and to raise their voices online, and I think there's a very inspiring story here about the resilience of people in one of the most censored environments in the world, still finding ways to express their beliefs about human rights, and to challenge the Iranian government. Now, unfortunately, I think it's also worth noting here that state repression in Iran was sprawling and not solely limited to the protest themselves. Two people were executed in Iran over the past year for allegedly expressing blasphemy over Telegram, and we also saw authorities pass a sprawling new law that actually expands their capacity for online censorship and surveillance through some very sneaky procedural measures that meant that it didn't get enough scrutiny from the limited ways that Iranian people can participate in legislative processes.

Justin Hendrix:

I want to touch on another country, India, which is one we've talked about in the past. In discussing this report, prior iterations of it, seems like things have continued to degrade there as well.

Kian Vesteinsson:

That's unfortunately the case. Now, again, I think it's really important to say that India is one of the world's most vibrant democracies. People really participate in political processes both online and off in really engaged ways. But the government has taken increasing steps to expand its capacity to control online content over the past year. A couple of years ago, the government passed new rules, known as "The IT Rules," which essentially empower authorities to order social media platforms to remove certain kinds of content under, so-called, emergency measures. Over the past year, the government took those emergency powers to restrict access to online content criticizing the government itself.

In one very prominent case earlier in 2023, authorities restricted YouTube and Twitter from displaying a documentary about Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi's, government background from viewers in India. The documentary looked at Modi's tenure as chief minister of Gujarat, during which he presided over a period of intense unrest and communal violence, and quite frankly, it's important for people in India to be able to understand the political history of their prime minister and access information about his government decisions. The Indian government's decision to restrict access to that information, within India, cut people off from some really important context. We also saw Indian authorities continue their practice of issuing incredibly over-broad and long-term internet shutdowns during times of crisis. Just recently, in the past month, authorities in the state of Manipur ended a 150-day-long internet shutdown that was first imposed in May.

Manipur saw some really tragic and egregious violence during that period, stemming from a conflict between two tribal communities and, in times of conflict, it's really important that people are able to access the internet to coordinate on their own safety and get access to health information when they need it. Shutdowns like this are incredibly restrictive and have really severe impacts on people in a time of crisis.

Allie Funk:

I might just chime in here on why India is so important in the global fight of internet freedom and beyond the fact that it's home to... Is it the largest market now of internet users? Maybe the second or third, my stats in my head are a little... Yeah, after China. It is such an important country when we're thinking about how to resist and how to respond to China's digital authoritarianism and the Chinese government's efforts to propagate their model of cyber sovereignty abroad. It serves as a really important regional lever here. We like to talk about India, also Brazil, Nigeria, these swing states of internet freedom, because they oscillate between these two worlds, like Kian mentioned, about the vibrancy of the online space. We've seen a lot, how the US government is trying to build better connections with Modi, BJP, and the Indian government broadly as a way to counteract China and have larger influence.

This is not just with India. Biden went to Vietnam, you're seeing this with Japan and South Korea as well, so India is part of this, but when thinking about... I sometimes worry this increased effort to pull India in, but doing that at a time in which human rights are on the chopping block within India, is deeply concerning. How can we, as democracies, and the US, the European Union, other countries within BRICS like South Africa, how do we balance that, right? How do we pull India in, but also do a carrot-and-stick approach where you're also trying to incentivize it to improve its behavior? Because I do worry that, in some sense of pulling them in, we're giving a pass for some of this. Especially ahead of general elections next year in India, which are going to be such a pivotal moment in Indian democracy and the future of it, we really need to think creatively about how to try to incentivize the government to improve its own standards.

Kian Vesteinsson:

The same goes for companies that operate in India. The next year is going to be really pivotal for online speech in the country as people head into an election that could very well represent a challenge to the ruling party, and as we all know, elections are a flash point for these sorts of online censorship. Social media companies that operate in India need to be prepared to face an escalating volume of content removal requests about sensitive content relating to political figures. It's very likely that people in power, prominent politicians from all parties, could seek to exercise control over platforms to remove critical speech. It's essential that the companies be prepared to push back against those requests, as much as is feasible within India's legal framework, to ensure that people have access to information about the elections during the electoral period.

Justin Hendrix:

Not just India, but many other countries having elections, including notably the one that we are all sitting in, the United States. How does the United States fare on this ranking?

Allie Funk:

The United States, we rank it eighth. It's tied with Australia, France, and Georgia. Internet freedom, it's trekking along in the United States. We are one of the leaders in the whole field of internet freedom, that's where some of the terminology actually comes from, the United States and Hillary Clinton when she was Secretary of State and really bolstered this approach. Continuing on that, I think there are two interesting tensions that happened when we think about the state of human rights online in the US. Internationally, this started last year, but also continued this year, the Biden administration has put internet freedom at the forefront of its foreign policy and it's created really real results from that. Everything from creating a new cyber bureau in the state department that has its own digital freedom component. We now have a cyber ambassador, tech ambassador, Nathaniel Fick, the Biden administration has put millions in Congress as well, millions of dollars in programing around digital democracy.

We've rolled out a really welcome executive order that limits the federal government's use of spyware under certain circumstances, so really impressive movement here when it comes from the administration. In the last... How could I forget that we've been chair of the Freedom Online Coalition for the past year? The sticky point is that we're not seeing that movement domestically, particularly as it relates to action from Congress. I think a little unsurprising, Congress has not been able to... Has struggled with passing meaningful legislation on a whole host of issues, so it's not surprising they're lacking on... Still don't have a privacy law, we still don't have a movement on platform responsibility and transparency, and it's not from a lack of bills. There was a really fantastic that we endorsed, privacy law, that was proposed last Congress. Didn't make it through.

It was bipartisan, it had a lot of support from civil society, even some industry. It's just this really alarming juxtaposition and I think the way we think about it is... In order for the United States to be a successful and effective advocate of internet freedom abroad, we've got to get our own house in order, and we've got challenges with disinformation proliferating online, you've got actors within particular parties that are driving that themselves. With this past year, I think one of the big things that changed is that you have so much internet regulation at the state level, some of which is good, you got a lot of good data privacy laws at the state level, but a lot of it is bad for free expression and access to information.

I think the biggest example of this just is in Montana. The state passed a bill that forces Apple and Google to remove TikTok from their app stores. It'll go into effect January, it's been challenged from a constitutional perspective, so I'm skeptical. I'm not a lawyer, but I'm skeptical it'll go through, so we'll have to see. It just speaks to the ways in which states are stepping up to take these issues head on, but in a way that isn't always beneficial for internet freedom.

Justin Hendrix:

I'm speaking to you on the morning, we've learned that Supreme Court will, in fact, take up the question of whether Florida and Texas must-carry laws are constitutional or not. A lot working through the courts, including the big Missouri versus Biden case, which will potentially also end up before the court, so quite a lot could change here in the next year.

Kian Vesteinsson:

Justin, I was really holding out hope that we would break the news to you on your podcast, about NetChoice getting cert, but that'll have to be at another time. Listen, I think these are some really big questions in the cases that you've alluded to, and certainly, I don't feel comfortable saying that we have the answers to what the court should do in either of these really big cases, but what I'll say here... A couple of things, platforms have too much power, full stop, over what people can or cannot express online and, certainly, that power is concentrated, right now, in relatively few companies, but the must-carry requirements that we saw coming out of Florida and Texas that are the question in that choice are misguided. They're tying the hands of social media platforms to enforce their own terms of service and to do the critical work of reducing the spread of false and misleading content and hateful content online.

What's really critical that governments at the state and federal level focus on legislative frameworks that push for transparency, ensure that researchers have access to data about how information spreads on the platforms and the mitigation measures that are in place, and it's really critical that states and the federal government take action to limit what data can be collected and used in these sorts of content recommendation systems. Certainly, I think the concerns that are raised about the power of these platforms over people's speech are very valid and really important to contest, and the sorts of discussions that are coming out of these cases are really important, but the Florida and Texas must-carry laws are simply the wrong approach to doing so.

Justin Hendrix:

So when I do a search for the term "Good news" in this report, I get no results found, but there must be some good news in the world, so please, leave my listeners with some hope that things might improve.

Allie Funk:

I think there's a lot of good stuff, actually, that's coming out and it often takes time for efforts to show up in the research. Let me say top line. Over the past two years... It relates to what we were talking about, with the US and the Biden administration's efforts to incorporate internet freedom within its foreign policy. There has been a lot of really wonderful movement strengthening democratic coordination on these issues at the multilateral level, and those efforts take time to key results. Very specifically, one example we highlight is around the global market of spyware, there's been so much movement trying to reel back that market. Biden administration's executive order that limits the federal government's use of it is huge, because it sets standards for democracies around the world about what they should adopt at home.

The Biden administration has also put on the entity list NSO group and a few others, which is actually having a real impact then on the market. We're going to start seeing how entity lists export controls, Costa Rica's government called for a full moratorium on these tools, how that is going to play out, and I think there's already one really interesting example in which the Indian government was reported was looking for less powerful tools on spyware than NSO because of issues with reputation by using NSO. That's one good movement, there's just been really great coordination between industry, government, and civil society on that. I think another area I'd highlight is the ways in which digital activism and civil society advocacy is driving progress, and a lot of times, they're pushing courts to behave in a way that protects human rights. We have plenty of examples this year where judiciaries, especially in countries that are partly free or not free, where you think the judiciary might be captured by a political party or captured by those in power, and it's not, it's still holding up and pushing back against what the government's doing.

A really good example, I think, is in Uganda, which Uganda, interesting enough, in our report over the past decade has declined the third most than any other country. It's just growing more repressive by the day almost. The constitutional court there repealed a section of the Computer Misuse Act that was used to imprison people. I think this is such a good example, because at the same time that the court did that, the government passed a really alarming law that imposes 20-year prison terms for people who share information about same-sex sexual content that we expect to be wheeled against the LGBTQ community in the country. It really leaves hope that the judiciary, there's space there. With all the doom and gloom, I hope that readers also see the positive story and we wanted to end the report on, hey, we're not screwed over here.

There's a lot of lessons learned that we have all collectively learned together about what works to protect internet freedom and candidly what doesn't work, and we call for governments and industry and civil society to internalize these lessons and make sure that we applaud them moving forward, especially as AI is exacerbating internet freedom's decline.

Justin Hendrix:

Allie, I want to indulge that optimism and yet, on the other hand, 13 years of things moving in the wrong direction, a lot of challenging choppy waters ahead, as a lot of big problems like climate change and even more profound inequality come along. One could read your reports and walk away with the sense that there's a valence to technology that is leading us towards a more repressive and authoritarian world, and I find myself concerned that's the case. Clearly, that's what this podcast is about on some level. How do you think about that?

Kian Vesteinsson:

Justin, I like the idea that this podcast is basically just talk therapy to work through this fundamental fear, which I share. I think it can be really hard to be optimistic about the future of the internet, but let me get personal here. I grew up online and I learned about who I was as a queer person because of having access to this enormous scope of discussion of people sharing their fundamental experiences of who they are and how they live life. That was really instrumental for me. I think that promise of access to information, of access to a greater understanding of who you are as a person still holds. There are still these spaces where people can turn to the internet to express themselves in ways that they can't necessarily do in their offline lives. Part of the goal of our project is to call attention to these contexts where censorship and surveillance is so extreme as to limit those fundamental acts of expression and security in the self, but where I really find optimism in all of this is that this promise is something that people are still mobilizing around.

There's a really powerful example over the past year in Taiwan. Taiwan is one of the freest environments when it comes to human rights online in the world, certainly in the Asian Pacific region, but technology experts recently started noticing that there was a growing number of domain-level blocks that were being reported in the country. These sometimes crossed over into the internet that most of us spend our time on, Google Maps or on PTT, this very popular bulletin board in Taiwan, so they started looking into this. This technologist started diving into what was going on and what they found indicated that the Taiwanese authorities had implemented domain-level blocking and astounding number of cases that were not publicly reported, and they went to their internet regulators and said, "What's going on here? This is really concerning."

This prompted regulators to disclose a whole bunch of information about how law enforcement agencies operate this domain-level blocking system, this DNS blocking system, in cyber crime cases, sharing more information about what was going on with regard to this system and, in doing so, creating a greater avenue to push back on this sort of censorship system. Now, there's obviously legitimate reasons that governments may want to curtail the activities of cyber fraud websites and other forms of outright criminal content online, but it's apparent that they do so in the daylight, that people understand what is going on and what systems are in place to ensure accountability and oversight. These technologists mobilized around this idea that they should know what's happening to the Taiwanese internet at the government's behest. It's little stories like this that tell me that people around the world still see this internet as a place of promise and something that they're willing to fight for.

Allie Funk:

I might also just add, how long did it take us? Us, I was in, what? Middle school and high school, so I'm using "Us" generously here, but how long did it take us as a community to talk about internet regulation? Took years, right? We thought, "Oh, my God. Look how great these services are," and then social media came, "It's going to be awesome," and then we were like, "Oh, heck," I don't know if I can cuss on your podcast, but, "Oh, heck. We need to do something, these platforms are running amok," et cetera, et cetera, "They're leading online violence, they're contributing to genocide," so on.

We have had generative AI on the scene since November, I know that AI regulation discussions have been going on for a long time before that, but the speed with which so many people are like, "We need to regulate this, we need to figure out how to make it safe, fair, how to make sure it's protecting human rights, not driving discrimination, and protecting the most marginalized communities," that is such a difference in how we approach technology, which speaks to we've learned a lot of stuff and we're actually making a lot of progress. Even if it's not yet coming up in Freedom on the Net, I'm very hopeful that one day it will.

Justin Hendrix:

I suppose in the face of all of these declining statistics, I always say, "Look for the helpers." You are two of them. I know, also, that this report is the product of many hands, including people all around the world and individuals who are, in fact, in some of these reports' context. Can you just give my listeners a sense of the methodology briefly and how you put this thing together, so they have an idea of how it works?

Kian Vesteinsson:

I love to talk about our process and particularly this network of contributors. This year we worked with over 85 people to produce this report, and these are human rights activists, journalists, lawyers, folks who have lived experience in fighting for digital rights in the countries that we cover. For every country that we cover in this report, we're working with a person who's based in that country where it's safe. As you can imagine, there's a number of countries where it is not possible for Freedom House to safely partner with someone, so we work with a member of the diaspora community, someone who's working in exile, for example, to put out that country report.

Through a pretty extensive process that starts in January and February and wraps up around this time of year, we take a deep dive into conditions on the ground in each of the countries that we cover, and our focus here is on understanding people's experience of access to the internet, restrictions on online content, and violations of their rights, like privacy. One part that's a really critical component here is making sure that we bring our researchers together to talk about the different developments that are happening in their countries, and we really look for opportunities to put the comparative part of our project up front, giving folks a chance to understand how developments in Thailand may relate to the fight for free expression in Indonesia. These comparisons can really strengthen the fight for internet freedom around the world, and it's honestly a privilege for us to be able to facilitate folks sharing information around that through Freedom on the Net.

Justin Hendrix:

I want to thank the two of you for speaking to me again this year about this report and I will look forward to, hopefully, year number 14 being the year that things finally turn around. I think I said that last time we spoke, so I'm not going to put too many eggs in that basket, but either way, Kian, Allie, thank you so much for speaking to me today.

Allie Funk:

Thanks so much, and thanks for all your great work at Tech Policy Press. It's a fantastic resource putting these issues on the map.

Kian Vesteinsson:

It's always a pleasure, Justin.

Authors