Can a 'nutrition label' shape Big Tech data privacy norms ?

Joël Carter / Jan 5, 2021In 2008, Apple’s App store only offered 500 apps. It has since expanded to over 1.5 million and, in a lot of ways, mimics the real-life grocery shopping experience. For seemingly every need, “there’s an app for that.” Vibrant colors of the apps attract the eye similarly as do the variety of fruits or vegetables on the produce stand. But in a grocery store, a customer can compare costs, preferences, ingredients and consider the key features of an item by referring to a nutritional label. Could the same principle work for software?

Redesigning privacy as nutrition

A quick search for “encrypted messaging” within the App store provides results, for instance, for Signal and WhatsApp. Both essentially serve the same purpose, which is encrypted communications. However, Signal provides superior privacy features, like encrypted metadata – a notable point of differentiation.

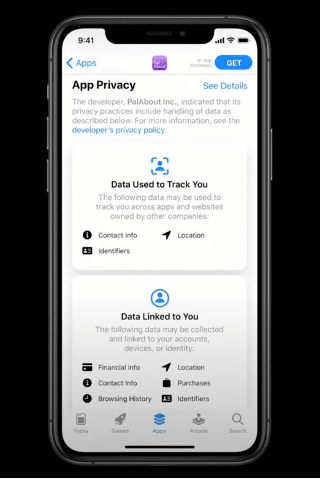

As of last month, Apple applies the same logic of a nutrition label to the App store so users can digest the different “data types the app may collect, and whether that data is linked to them or used to track them.” This information is now required for developers to update and submit new apps to the App Store. The information will be located on each app’s product page and will list privacy details about contact, health and fitness, financial information, location, user content, browsing and search history, identifiers, purchases, usage, diagnostics, and other types of “significant info” and data collected.

Beyond catering to consumer preferences, what is Apple’s incentive and strategic aim in creating the new tool? Maybe it’s the looming threat of federal regulation of the tech industry and a desire to demonstrate that the company is able to keep itself in check.

The label boosts user privacy and information because information about data collection, and by whom, is made transparent. Facebook, on the other hand, begs to differ, purportedly on behalf of small business owners. Last month, Facebook condemned the labels saying, “Apple’s latest update threatens the personalized ads that millions of small businesses rely on to find and reach customers. We’re giving small business owners a place to speak their mind.” The social media platform also rebuked Apple’s future plans to give users the option to allow ad tracking – a position to which Tim Cook swiftly replied in a tweet. Facebook’s subsidiary, WhatsApp, offered criticism, too, saying that Apple did not hold itself to the same standard. Apple has since clarified that its own pre-installed apps (i.e, GarageBand) abide by the same standard. For iMessage and other built-in apps, which have no product page on the App Store, the same privacy information will be found on Apple's website, per Axios.

Tech’s “Thrilla in Manila”

The face-off between Uncle Sam and Big Tech has long been expected, a match not even the assault of Covid-19 could postpone. Government officials in both parties have been vocal about the need for greater oversight of the technology industry. The cacophony surrounding Apple, Facebook, Google, and Amazon’s market power landed all five CEOs virtually testifying before Congress in recent weeks, and certainly did not bolster the image of these companies as champions for consumer preferences. While the hearings were mostly about competition, data privacy practices are also in the crosshairs.

The concern over data privacy practices has compounded since the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2017. The increasing number of state-level regulations exemplify the growing attention on and demand for stronger data privacy. In 2020, California, New Hampshire, New York, Oregon, Virginia, and Washington all either introduced or passed legislation to increase protection for consumers’ data privacy. The level of influence Apple wields within the industry is monumental, and introducing a new tool that clearly communicates a summary of data privacy practices could shape industry practices, especially as reports of data privacy malpractice continue to surface.

How can the label’s effectiveness be gauged?

Last month, Motherboard reported why the stream of data that flows to apps we use is worrisome. For instance, Muslim Pro is an app that reminds users of prayer times and what direction Mecca is relative to their current location. With 100 million downloads, it is incredibly popular. Muslim Pro, like many other apps, allowed third-party collection of the data it harvests from its users. Apps are monetarily compensated when they permit third parties to access user data. In this case, X-mode, a firm that sells access to location data and services, was found having supplied Muslim Pro user location data to the U.S. military. In this extreme example, the value of a privacy nutrition label with information about Muslim Pro’s data practices is clear: a label could have warned users. Suppose users were ultimately dissuaded from using Muslim Pro. The data from those who use the iOS version of the app would have been spared from entering the location data supply chain. The bulk of Muslim Pro’s downloads (50 million) were on Google Play. Google has not announced a plan to roll out its own version of a nutrition label – perhaps the distinction makes clear why it should do the same.

It is increasingly in the interest of corporations to debut new tools that provide effective data privacy protections. Doing so: (1) satisfies consumers’ demand; (2) signals a willingness to address issues salient to government entities; and (3) displays an ability to lead the industry by shaping industry best practices. It’s unlikely that a privacy “nutrition label” created in the spirit of consumer protection is sufficient to stave off the possibility of federal regulation, which may well be on the horizon in the Biden era. But it may position tech companies who adopt it on the right side of history.

Authors