DOJ vs Google: Back to Court for Remedies to Break Digital Ads Monopoly

Karina Montoya / Sep 22, 2025Karina Montoya researches and reports on broad media competition issues and data privacy for the Center for Journalism & Liberty at the Open Markets Institute in Washington, DC.

November 24, 2023: The Google logo is seen at Google's new Bay View campus at its headquarters in Mountain View, California. Shutterstock

The United States Department of Justice and Google will face off again today in federal court in Virginia. This time, the parties will argue about the types of remedies the court should impose to unwind Google’s illegal monopoly in the ad tech market.

The remedies phase, slated to last two weeks, follows a ruling by Judge Leonie Brinkema that found Google liable for anticompetitive practices to favor its own ad tech business, crushing competitors and going against the interests of publishers. Invisible to users, ad tech platforms have become key intermediators that manage and execute ad sales across the web for publishers — mainly news publishers — and advertisers, driving a digital ads industry worth more than $300 billion in the US as of 2025.

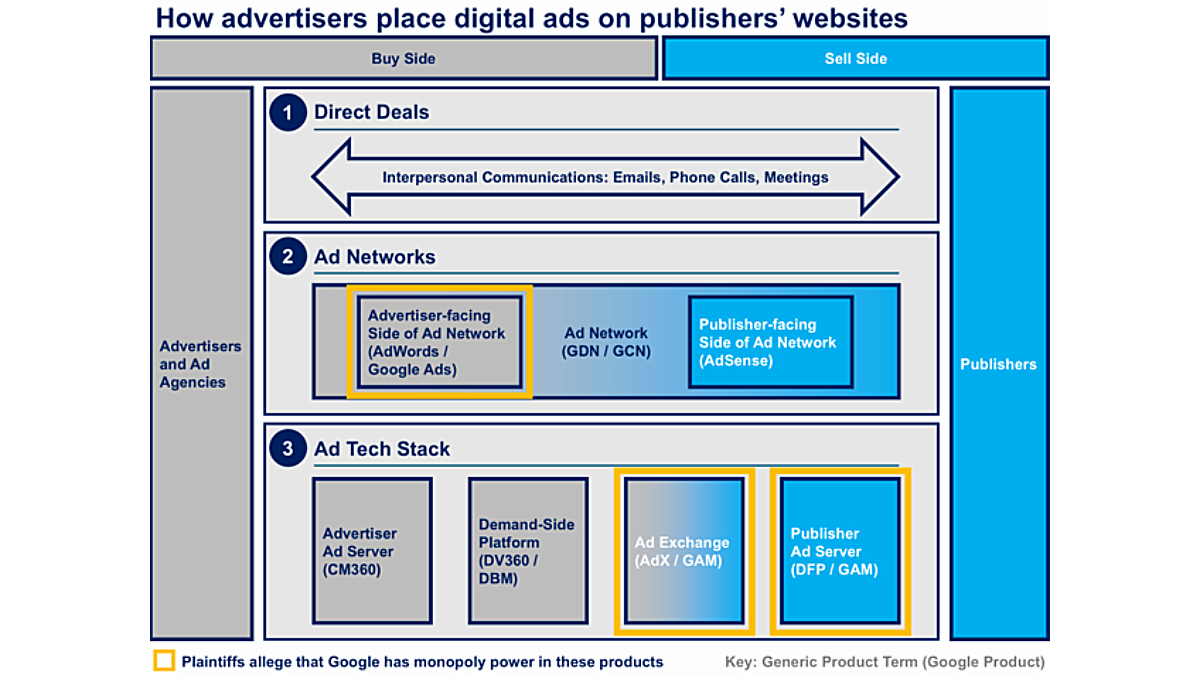

How advertisers place digital ads on publishers' websites. Source

Google’s ad tech business, made up of fees charged to publishers and advertisers, posted $30 billion in revenues in 2024, double from a decade ago, per SEC filings. During that period, revenues from Search and YouTube have multiplied five fold to $234 billion. By contrast, the US news media market — the core of Google’s ad tech customers on the supply side — has seen print ad revenues shrink from $12 billion in 2017 to $5 billion last year, with digital ad revenues remaining stagnant at $5 billion annually, according to Axios.

The remedies hearings for the Google Ad Tech case will mark the second attempt by the DOJ to convince a federal judge that a combination of structural separations and behavioral changes is needed to pry open markets monopolized by Google. Earlier this month, in a separate case against Google’s search monopoly, D.C. District Judge Amit Mehta sided mostly with Google’s remedies proposal. He rejected the DOJ’s request to spin-off Chrome and allowed Google to continue making payments to Apple and other phone providers to make Google their default search option.

To help Tech Policy Press readers consider the news out of the court over the next two weeks, here’s a run-down of the main proposed remedies by each party that we can expect will be at the center of the arguments in the proceedings:

Divestiture of Ad Exchange (AdX)

A key DOJ proposal is the sale of AdX, Google’s ad exchange. This tool gathers bid requests from advertisers and runs milli-second auctions to match them with publishers. Ad exchanges have a key role in routing advertiser demand to publisher ad servers, which are the platforms that deliver ads on publishers’ websites.

In her ruling, Judge Brinkema found that Google illegally tied AdX with its publisher ad server, DoubleClick for Publishers (DFP). The product tying in turn helped Google maintain its monopoly in detriment of publishers’ interests. Google acquired AdX as part of its purchase of the company DoubleClick in 2008.

Before the acquisition, publishers, whether or not they used DFP or AdX, were able to connect with advertisers using Google tools. But shortly after merging with DoubleClick, Google changed its policies: It turned AdX into the only platform that Google’s largest advertiser base — known as AdWords — could use to connect with publishers. At the same time, it required publishers use DFP to access advertiser demand coming from AdX.

Through these two policies, AdX became the “glue that sealed DFP” [ad] inventory to AdWords demand, the ruling concluded. Although publishers could offer ad inventory to other ad exchanges, they would not get enough demand, since AdWords was restricted to bid only on AdX. This turned DFP into an essential product for publishers, despite their efforts to lessen their reliance on Google’s ad tech stack.

During the liability trial in September 2024, the most revealing evidence that this product tying was anticompetitive came from Google’s own engineers. Internal documents showed Google’s executives knew AdX served to extract “irrationally high rents” from publishers, as the corporation was able to keep a 20% usage fee per ad sold for more than a decade, based solely on AdX being the exclusive access channel to AdWords demand.

Phased divestiture of Publisher Ad Server (DFP)

Alongside selling AdX, the DOJ also proposes that Google spins-off its publisher ad server, DFP, in two phases. The first phase consists in making the ‘final auction logic’ of DFP into an open-source mechanism, which will be administered by an independent organization. The goal would be to cut Google out of deciding which advertiser bids win an auction, which ads are served, and how prices are calculated per Google’s policies.

According to the DOJ proposal, this means Google would have to replicate the ‘final auction logic’ integration, turn it over to an independent organization through a non-exclusive, free-of-charge license, and then disable its own ‘auction logic’ codes within DFP — which Google would still be able to operate.

The open-source ‘auction logic’ would enable publishers or other ad tech competitors to create their own versions, which would work with both non-Google publisher ad servers and DFP itself. In practical terms, Google would have to connect to a third-party to make DFP work, and decisions about displayed ads and prices would be in the hands of publishers or other non-Google partners.

The second phase would be a full divestiture of DFP, contingent on whether Google’s unlawful conduct has stopped. That determination would be made by an independent court-appointed monitor, which would conduct an investigation into the impacts of the structural remedies no later than four years after their implementation.

Escrow proposal funded by Google

Somewhat buried in the list of DOJ’s proposed remedies is a request to create an escrow account funded by Google’s half of revenues coming from AdX and DFP, starting from the day of the liability ruling on April 17, 2025. In the case of AdX, the funds would be counted until the closing day of its sale. For DFP, the cut-off date for funding would be either the date the monitor determines whether or not to sell DFP or the closing day of its sale.

The funds would be destined for three purposes: to cover the costs of publishers switching their ad inventory from DFP to other competitors, to cover the costs of the administrator of the open-source auction mechanism, and for any other remedial need ordered by the court. Although it is unclear how big the escrow could be, if we take only half of Google’s revenues from its ad tech stack, that figure would be $15 billion considering only this year.

Behavioral remedies: some common ground

Google and the DOJ do agree on a list of what they see would be prohibited behaviors moving forward. For example, Google proposes to stop making AdX the exclusive channel for AdWords advertisers to reach publishers, and that publishers shouldn’t have to manage their ad inventory with DFP to access AdX demand. Google would also have to interoperate with header-bidding technology — the main one being Prebid, whose former executives were key witnesses in the liability trial — and integrate with it in equal terms as Google does with DFP and AdX.

Google is also proposing to get rid of policies made to stifle competition, such as Unified Pricing Rules, which prevented publishers from maximizing ad revenue through other ad exchanges while reducing reliance on AdX. Moreover, to ease publishers’ technical burden and costs of switching away from DFP, Google also proposes to provide tools to transfer publisher data to any non-Google publisher ad server.

Google’s proposal: focus on the behaviors, leave the rest alone

But there are more differences than common ground in the two parties’ proposals. Google’s position is that it should be enough to restore competition to the state prior to its illegal practices. In that sense, they oppose the DOJ’s attempt to make the court even consider that the proposed divestitures are appropriate because they are “unworkable.”

Google is also using the remedies ruling in the Search case to argue that separations of Google’s technologies are “uncertain to succeed,” and the court should be skeptical of “product degradation” and “loss of consumer welfare.”

Google also proposes that the supervision period for compliance be six years, instead of 10 years as proposed by the DOJ. About the court-appointed monitor proposed by the DOJ, Google wants the monitor to be selected by a three-party agreement between the DOJ, a committee of plaintiff states and Google itself, subject to approval by the court.

Does the DOJ stand any chance?

Taken all together, the remedies hearings for the Google Ad Tech case are likely to pit equally contentious positions as the remedies phase for the Search case did. Perhaps the biggest difference is that the DOJ built the Ad Tech case with structural remedies in mind, which can be seen in the filing of the lawsuit in 2023. Throughout the liability trial, evidence was put forward to feed the need for both behavioral and structural remedies.

But the DOJ will still need to make the case for the feasibility of its proposal. In light of the Search remedies rulings, the DOJ will also have to discuss how those remedies either make things better or worse for competition in digital advertising. Most importantly, it will have to clearly show that without both behavioral and structural remedies, little not nothing will be achieved not only to restore competition prior to Google’s monopoly, but also to prevent future illegal conduct.

Authors