Electronic Warrants Undermine Our Rights

Tracy Hresko Pearl / May 9, 2025

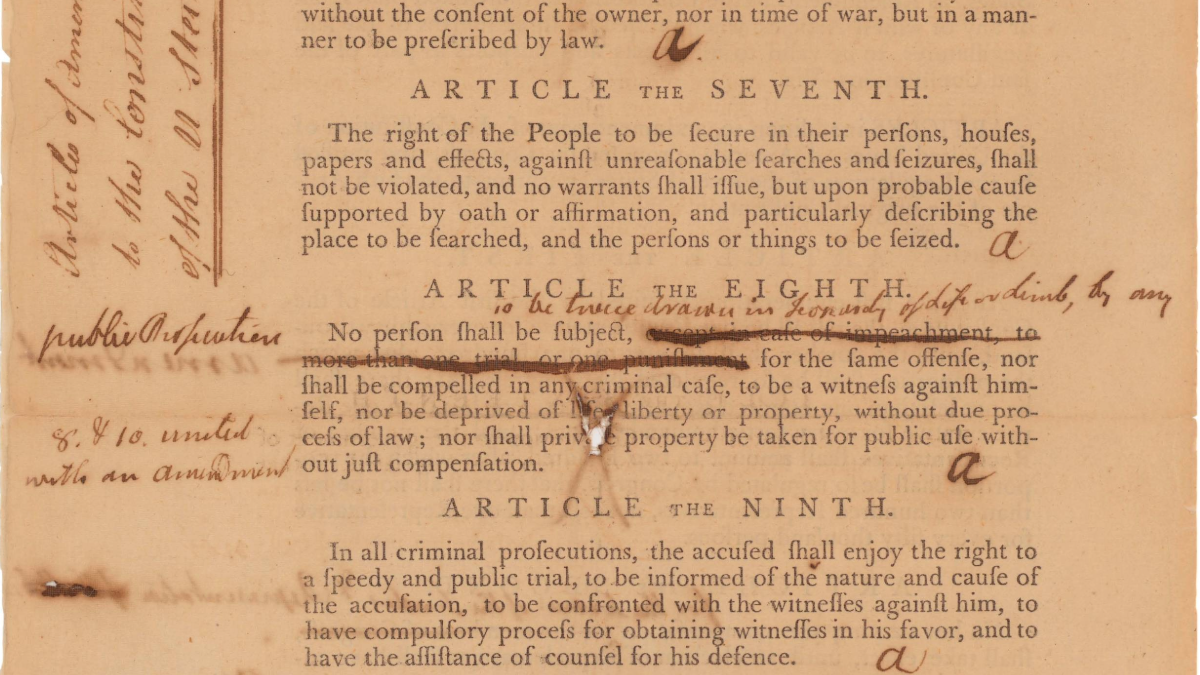

Senate Revisions to House Proposed Amendments to the US Constitution - September 9, 1789 (National Archives)

Early American colonists understood the terror that comes with the government entering your home without permission. Imagine the fear you would experience if police officers knocked down your door, burst into your home, and rifled through your possessions with no warning and no consent. Colonists experienced it far too often, and such searches were one of the motivating factors behind the American Revolution. For years, British Red Coats abused colonists under the authority of “general warrants,” which gave them the right to enter anyone’s home at any time to rifle through their possessions with just the barest suspicion of criminality.

The founding members of our country wanted to stop such abuses. To that end, they included the Fourth Amendment in the Bill of Rights. This Amendment requires the government to obtain probable cause and a valid warrant before searching “persons, houses, papers, and effects.” While not a perfect fix, the Fourth Amendment has done much to protect citizens from overzealous governmental searching and seizing.

One important way the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement has protected citizens is by making police obtain permission from a judge before searching someone’s home. Until recently, if officers wanted to get a warrant, they had to prepare a written application and affidavit, travel to their local courthouse, meet with a magistrate judge, and answer any questions that judge might have. This process took time and energy, meaning that police were disincentivized from seeking warrants without a high level of certainty that they had probable cause and a high likelihood of finding evidence at their intended search location. The inconvenience of the process, in sum, was a feature, not a bug, of the system.

New technology, however, has changed the warrant application process in troubling ways. Electronic warrant (“E-warrant”) systems are now in use in well over half the states and allow officers to apply for warrants electronically from anywhere they have a cell phone signal. Judges, in turn, can review those applications remotely and choose to issue or deny these warrants via a computer-based e-warrant interface, making the process about as easy as an online purchase. Additionally, they can do so without ever speaking to the officer who submitted the application. Use of this technology is growing, with one e-warrant company reporting that police have used its system to obtain over a million warrants throughout the United States.

At first glance, e-warrant technology is immensely appealing. It allows police to obtain warrants very quickly and without the logistical rigmarole of the traditional process. Additionally, the ease of applying for e-warrants increases the likelihood that police will do exactly what early Americans wanted them to do: get permission from a neutral magistrate before searching someone’s home. By eliminating the need to appear in person at a courthouse and submit a paper application, police can follow due process with less of a burden.

However, a deeper look at e-warrants reveals a number of troubling side effects. One investigation showed that many e-warrant applications do not receive even a full minute of review by judges, even though such applications typically run for many pages. Additionally, since e-warrant systems eliminate the need for a face-to-face meeting, judges do not have the same opportunity to ask questions and assess an officer’s credibility. Finally, because of the ease of the process, officers are no longer disincentivized from submitting deficient warrant applications, and instead have many reasons to “roll the dice,” so to speak: pressure to solve cases, a desire to act quickly, and a seeming lack of consequences for submitting a bad application. There’s no harm in asking, as the saying goes. The worst that will happen is that a judge will say no.

But judges rarely say no. Over 98% of all e-warrant applications are approved, compared to 92% of traditional applications. Worse, once issued, the likelihood a court will rule that the warrant was unconstitutionally issued is infinitesimally small: fewer than 0.9% of challenges to warrant-based searches succeed. The sum total is this: e-warrant technology incentivizes police to submit more warrant applications with less evidence. Judges, in turn, approve these applications in greater numbers and with less scrutiny. Citizens, whose homes or possessions are then searched, have virtually no viable recourse even if the warrant likely failed to meet the required constitutional threshold.

To be sure, there are many reasonable ways to use this technology. E-warrant software can be immensely helpful, for example, to police in remote areas without easy access to a courthouse. It can also be useful during natural disasters, pandemics, and other situations where it is unsafe or unreasonable to require police to meet face-to-face with a judge. And there are undoubtedly many conscientious officers and thoughtful judges throughout this country who are using this technology carefully and responsibly.

Advocates also argue that e-warrants are helpful in emergency situations where, for example, police need to enter a home quickly to save someone in danger. However, the Supreme Court has ruled that police do not need to obtain a warrant at all in “exigent circumstances” such as these. In fact, courts have always been extremely willing to waive the warrant requirement of the Fourth Amendment entirely when there are good reasons to allow the police to act quickly. E-warrants are only sought, therefore, in situations that are not emergencies.

These issues underscore the need for states to prevent e-warrants from becoming a tool for circumventing constitutional safeguards.

At a bare minimum, states should require that in-person conversations between judges and officers occur via phone or video streaming technology when e-warrant applications are submitted. They may also want to limit the use of e-warrants to situations in which it is unusually inconvenient or unreasonable to expect police to appear before a judge in person. Indeed, in a world where technology seems to be making virtually every task easier, it’s important to remember that certain things should be difficult. Getting permission to enter and search your home without your permission should be one of them.

Authors