Emerging Trends in State Cyber Policy During the 2025 Legislative Session

Shannon Pierson / Jul 22, 2025Shannon Pierson is a Senior Fellow of Public Interest Cybersecurity at the UC Berkeley Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity (CLTC).

The Alabama State Capitol building in Montgomery. Source: Carol M. Highsmith Archive collection at the Library of Congress.

After six years of expanded federal leadership in cyber defense, the Trump Administration has begun scaling back the federal government’s role, including by reducing the staff of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) by a third and shrinking its budget by 17 percent. President Donald Trump also issued an executive order that shifts responsibility for cybersecurity preparedness to state and local governments, asserting that cybersecurity “preparedness is most effectively owned and managed at the state, local, and even individual levels” with limited federal support. At the same time, Congress is not expected to renew a landmark federal grant program providing cybersecurity funding to state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) governments, which is set to expire in September 2025.

Amid these shifting headwinds, state legislatures are taking on the mantle of cybersecurity leadership. Local lawmakers across the country are continuing to pass prescriptive cybersecurity regulations for critical infrastructure sectors such as electric utilities, water systems, school districts, and healthcare – systems typically managed at the state or local level.

Surprisingly, cybersecurity remains an issue around which bipartisan consensus is the norm in state legislatures. Cybersecurity-related bills receive bipartisan, and sometimes unanimous, support from both Democratic and Republican lawmakers. While funding remains the largest hurdle to passage of state cyber legislation, states are becoming “laboratories of democracy” for experimentation and innovation in cybersecurity policy. It appears that states aren’t waiting around for federal direction, but are rather piloting new, novel approaches and regulations to support regional cyber defense and to develop their regional cyber workforce – such as civilian cyber corps, regional student-led Security Operations Centers (SOCs), and state cyber commands.

Each year, hundreds of cybersecurity bills are introduced at the state level. But which ones actually become law? In this analysis, I take a closer look at legislation passed in the 2025 legislative session to surface the trends in legislation across states. I explore questions such as, which sectors and entities are receiving the most legislative attention? What kinds of solutions are states advancing? What might these trends signal for the future of state-led cybersecurity?

Methodology

I reviewed 24 cybersecurity-related bills and 3 resolutions enacted by states during the 2025 legislative session. This analysis is a first step toward building a publicly available database of all cybersecurity legislation enacted by US states over the past three years.

Currently, no such resource exists to track nationwide trends in state-level cybersecurity policymaking and to identify cybersecurity gaps or policy areas in need of harmonization. As I continue to build this resource, I have begun surfacing some preliminary trends from the 2025 legislative session.

Summary statistics

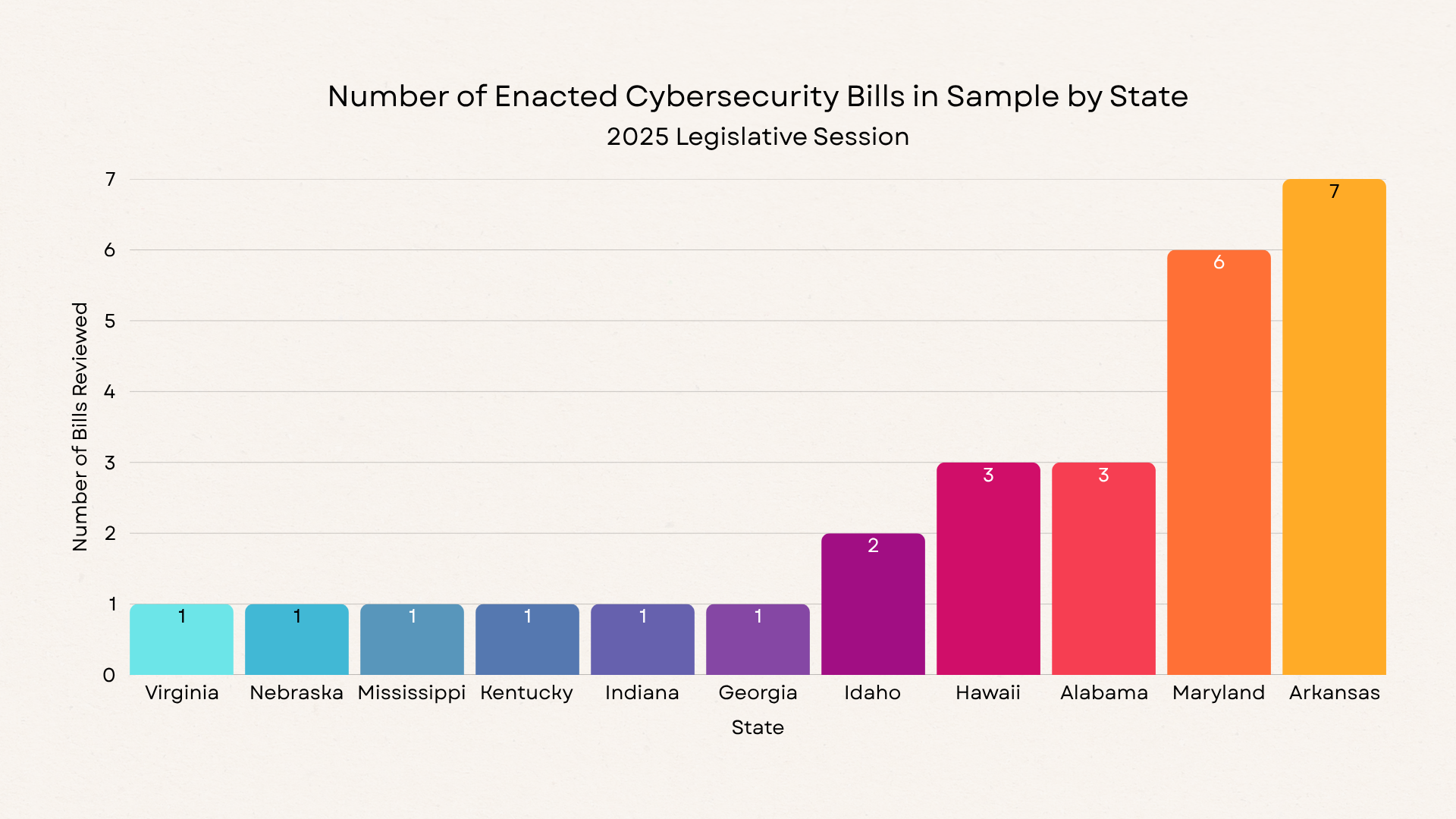

I analyzed a sample of legislation passed in 11 different states, with Arkansas and Maryland contributing the largest number of enacted bills. Across all 27 bills, I identified 77 cybersecurity-related actions enacted into law. About 11% of bills included funding provisions, appropriating a combined total of $38 million dollars. These bills took approximately 2 months and 1 week (67 days) on average to be enacted after their initial introduction. To generate this metric, we omitted resolutions because their passage timeline is generally shorter and they do not carry the force of law.

In the analysis below, I identify which entities and sectors were the subject of cybersecurity legislation passed in 2025, what kinds of solutions made it into law, and offer a few takeaways on what it means for the field.

Figure 1: Number of Enacted Cybersecurity Bills in Sample by State (2025 Legislative Session)

Which entities and sectors are the subject of cybersecurity legislation in 2025?

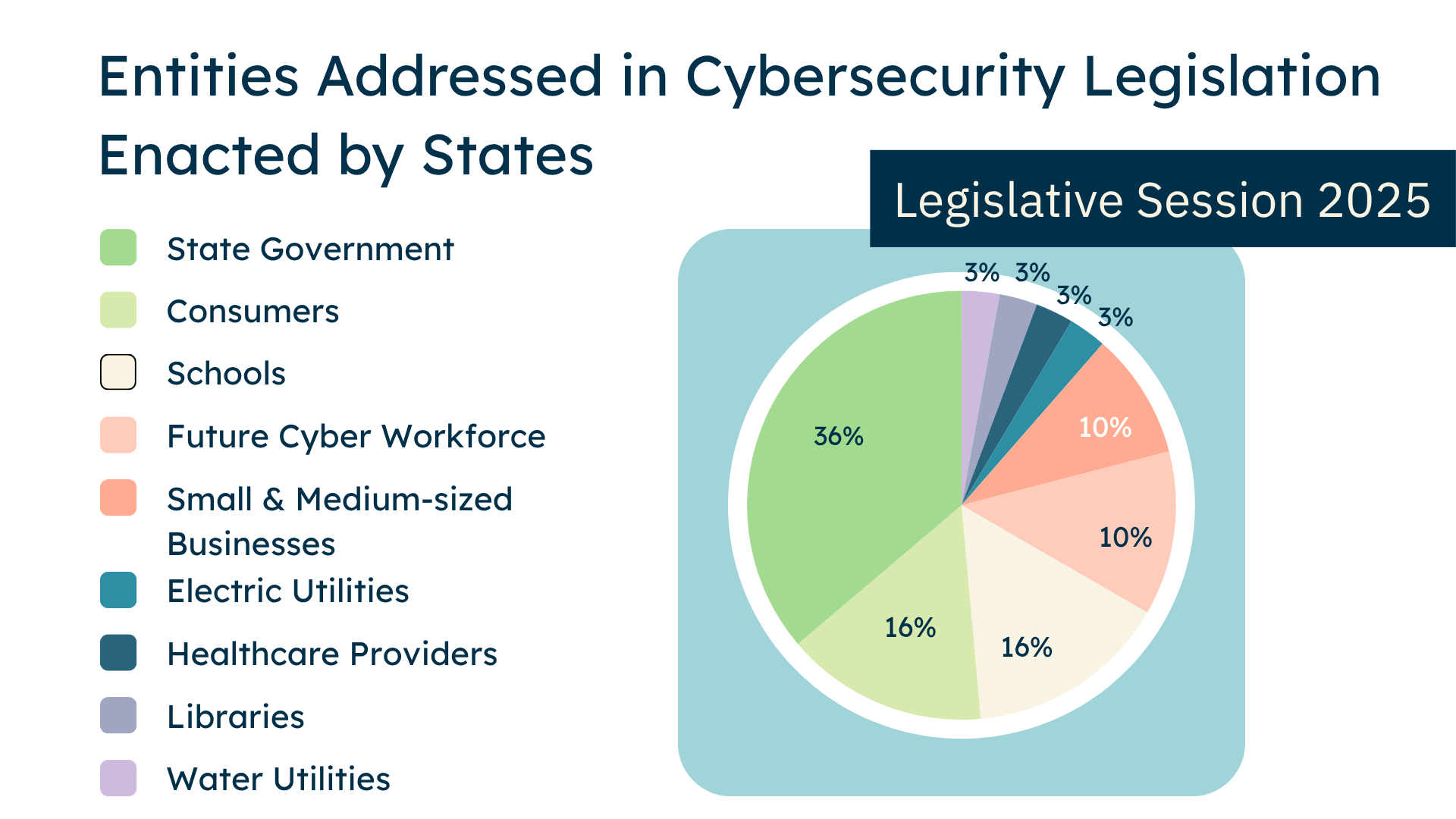

I categorized each bill based upon its intended beneficiary to identify which entities and sectors lawmakers are prioritizing in cybersecurity-related legislation in 2025. Three prevailing trends surfaced:

1. State government agencies were the primary focus of 2025 cybersecurity legislation.

Over a third of the bills (36%) aimed to shore up the cyber defenses of state agencies, often by expanding the responsibilities of dedicated state IT and cybersecurity offices. Most laws tasked these offices with formulating and enforcing cybersecurity standards across state governments, as well as serving as the central coordinator for cybersecurity resources and supporting regional public agencies, utilities, academic institutions, and nonprofits.

2. K-12 cybersecurity is receiving greater legislative attention and investment.

Legislative actions for cybersecurity of K-12 schools and universities tied with consumer protections as the second most common legislative focus (16%). K-12 schools and universities received $36 million dollars in funding for cybersecurity improvements and staffing. Considering that ransomware attacks on school systems are on the rise, with K-12 specifically becoming the most targeted industry as of 2024, this trend comes as no surprise.

For example:

- Alabama (AL SB112) allocated $23.3 million dollars for K-12 school districts to hire technology directors.

- Arkansas (AK SB481) tasked the State Insurance Department to establish and administer an insurance program to cover cybersecurity risks of public school districts, while also setting reporting obligations for their existing cybersecurity risk programs, including the expiration dates of their contracts and a history of their losses.

3. Strengthening consumer protections is becoming a legislative priority, with some caveats.

Some bills enshrined cyber hygiene obligations for entities managing sensitive consumer data, including financial institutions, entities storing genetic sequencing data, and governments planning on using generative AI and high risk AI tools to make consequential decisions about resources allocated to residents. This involved ensuring these entities were adequately resourced in terms of cybersecurity budget and staffing, effectively governed, frequently measuring and mitigating cyber risks, as well as utilizing cybersecurity best practices.

Beyond regulating these entities, some states also instituted their own support structures for consumers. Mississippi (SB2894) extended state insurance protections to include policies that provide financial protection of up to $300K in cybersecurity insurance if a licensed insurer becomes insolvent.

However, other bills were more sympathetic to cybersecurity challenges faced by small to medium-sized businesses. For example, one law passed in Nebraska (NB LB241) went so far as to grant private entities immunity from legal liability for cybersecurity incidents, unless it can be proved that the incident was caused by gross negligence. This weakened private sector accountability for data breaches and limited consumers' options for recourse.

Figure 2

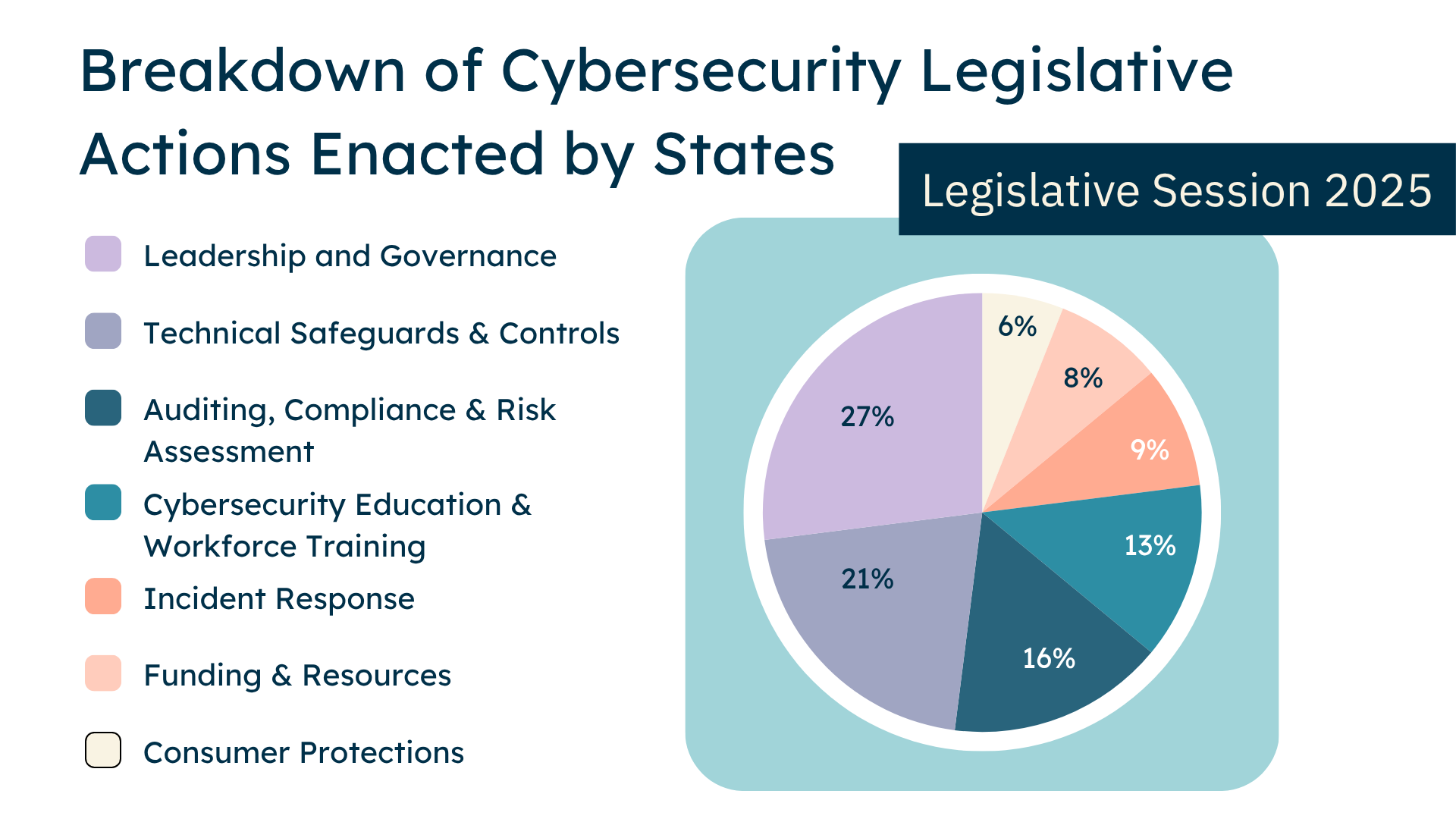

Figure 3

What types of cybersecurity solutions are becoming law in 2025?

I reviewed each of the 77 new rules and obligations established by passed cybersecurity-related bills and categorized them by issue area to reveal descriptive trends in the types of solutions state lawmakers are pursuing in 2025. This analysis reveals what actions lawmakers consider productive and necessary to address the cybersecurity challenges faced by the different stakeholders identified in Figure 2. I identified four emerging trends:

1. A quarter of all legislative actions focused on establishing leadership and governance structures to oversee cybersecurity coordination and programs within organizations serving the public.

Some bills (making up 27% of all legislative actions) set up systems for cybersecurity leadership and coordination by requiring states and financial institutions to establish offices or programs responsible for directing and managing cybersecurity and IT functions. These offices provide governance and strategic guidance in the form of standards and procedures.

For example:

- AR HB1557 & MD HB0236: Arkansas’s Division of Information Systems and Maryland’s Secretary of Information Technology were tasked with developing and implementing statewide cybersecurity strategic plans.

- KY SB4: Kentucky now requires its Commonwealth Office of Technology to assess cybersecurity risks, develop mitigation strategies, and enforce data protection in the government’s use of generative and high-risk AI systems.

2. Lawmakers exhibited a willingness to mandate the use of technical safeguards and controls into law, legislating the most essential and empirically-backed cybersecurity basics.

Numerous bills (making up 21% of all legislative actions) codified essential cybersecurity best practices into law, mandating the use of controls like access logging, encryption, access controls, asset inventories and multi-factor authentication (MFA).

For example:

- ID HB35: Idaho now requires all staff personnel in the state’s legislative and judicial branches, and in the offices of elected constitutional officers, to use MFA to access state IT devices or services, including email, cloud storage accounts, and all web applications. The law requires the use of phishing-resistant authentication methods, such as possession-based or inherence-based credentials as the second factor of authentication.

3. Bills set out to establish new audit, compliance, and reporting requirements for stakeholders on their cybersecurity practices.

Many bills (making up 16% of all legislative actions) included new obligations to monitor compliance and to track performance, as well as communicate those findings to relevant governing bodies.

These reporting provisions take various forms. Some require state IT departments to regularly submit cybersecurity compliance reports, performance metrics, or cost metrics on IT projects to legislative committees so that lawmakers can use it to inform budgetary decisions and cybersecurity legislation. Other bills required infrastructure operators to report directly to state IT departments to facilitate their oversight and enforcement.

Examples include:

- AR HB1549: Arkansas tasked the state’s cybersecurity office with auditing and reporting each state agency’s compliance with state and federal cybersecurity standards, policies, and procedures to the Joint Committee on Advanced Communications and Information Technology twice per year.

- IN SB459: Indiana required community water and wastewater utilities to certify biannually to its office of technology that they completed an annual cybersecurity vulnerability assessment, mitigated known vulnerabilities or developed documented mitigation plans, and updated their emergency response plans accordingly.

4. Many bills require organizations to establish incident preparedness and response plans to ensure they can quickly recover their operations after a cyber incident.

Several laws included provisions that required organizations to prepare for cybersecurity incidents, making up 8% of all legislative actions. Laws required state agencies and critical infrastructure operators to build incident response plans and teams, to create business continuity and disaster recovery plans, and to follow strict breach notification timelines. Across this legislation, there was a consistent focus on the necessity of preventing and preparing for service disruptions.

Some examples:

- IN SB459: Indiana now requires community water and wastewater systems to report cyber incidents to the state within 24 hours or 2 business days, depending on whether operations are impacted, and to annually designate a point of contact for cybersecurity incident reporting.

- VA SB1239: Virginia formed a working group to evaluate cybersecurity risks to electric utilities and cooperatives and identify what actions should be taken when a customer experiences an emergency condition that could compromise the reliability or security of electric service to others.

So what?

In conclusion, states are increasingly taking legislative action on cybersecurity by setting standards, allocating resources, and assigning responsibility to better protect critical infrastructure and consumers of digital services connected to essential services.

While there is a wide range of policy approaches and solutions being pursued, legislating for improved cybersecurity appears to be a bipartisan effort—with 59% of enacted legislation introduced by Republicans, 19% by Democrats, and 22% by entire subcommittees. While this breakdown may appear weighted towards Republicans, it reflects the fact that most of the laws in this sample came from states with Republican majorities in the legislature.

Based upon these early findings, here is what I predict we can expect to happen next in state-level cybersecurity policy:

1. State lawmakers will likely continue formalizing the roles and responsibilities of their own state agencies in coordinating cyber defense for operators of regional critical infrastructure like municipal governments, schools, and electric and water utilities.

These local actors are increasingly targeted by cybercriminal gangs and nation-state-affiliated actors, and are among the least equipped to handle them. Just because federal funding is drying up and federal leadership is withdrawing, it does not mean that these actors are scaling back their adversarial operations. In fact, we will likely see the opposite. States will likely be forced to continue stepping in to close the gap.

2. Cybersecurity requirements for critical infrastructure operators are shaping up to take the form of a state-by-state patchwork.

This fragmentation reflects what we have already seen with privacy and AI regulation, and may create some complex and contradicting compliance burdens for multi-jurisdictional infrastructure operators. However, this fragmentation offers opportunities for state-led innovation. States can experiment with “whole-of-state cybersecurity” strategies and related programs that consider their local threat landscape and institutional capacity.

3. Critical infrastructure operators at the state and local level will likely struggle to comply with new regulations unless those mandated are accompanied with appropriated funding to hire cybersecurity personnel and invest in necessary upgrades.

Regulation alone does not guarantee compliance. For example, consider the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). In 2013, Congress amended the SDWA by adding Section 1433, which requires community water systems serving more than 3,300 people to conduct risk and resilience assessments and to create emergency response plans addressing cyber incidents. Over a decade later, in 2024, the EPA reported that 70 percent of the water systems it had inspected since 2023 were in violation of these requirements. Suffice it to say, even the most well-intentioned, empirically-backed policies with legal force may fall short without the financial resources needed to implement them.

Next steps

There is still much to learn from this burgeoning body of legislation, and this brief analysis is just the beginning. This project sets out to build a publicly available database, hosted by the UC Berkeley Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity, of all enacted cybersecurity-related bills from all 50 US state legislatures passed between 2023 and 2025. The data will be cleaned and coded to track nationwide trends in state-level cybersecurity policymaking and to identify cybersecurity gaps or areas of emerging focus.

As I continue building this resource, I will publish future analyses that segment data by sector to surface cyber policy trends specific to each domain. One of the goals is to create a tool that can be used by researchers, policymakers, and government officials to identify opportunities for policy harmonization and to highlight promising (or concerning) cybersecurity policy templates that other states—or even countries—can reference, adopt, or adapt.

In the meantime, cybersecurity will be among the policy topics discussed at the upcoming 2025 National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) Summit, scheduled to take place in Boston from August 4 to 6. The Summit, the largest annual gathering of state lawmakers and legislative staff from across the country, will feature sessions on cybersecurity for the energy supply chain and election infrastructure and discuss how federal tech policy impacts state-level cybersecurity efforts.

Authors