Four proposals to neutralize social media’s threat to democracies

Chimène Keitner, Ram Fish / Jan 20, 2022There is no silver bullet to solve the problems created by social media companies. But these four steps pave the way toward a healthier future.

Ram Fish is the CEO of 19Labs and Chimène Keitner is Alfred & Hanna Fromm Professor of International Law at UC Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco.

We are only beginning to grasp the impact of social media on human society. In our view, the most urgent concern is how social media platforms contribute to democratic erosion. We agree with those who point to the advertising business model as the catalyst for platforms’ role in exacerbating political extremism globally and other negative externalities

The challenge in mitigating this threat is enormous: it requires a multidisciplinary approach, demanding insights from psychology, economics, law, business, and technology. There is a lot we don't yet know about the problem and how different variables impact it. Meanwhile, reform proposals must contend with strong political interests intertwined with fears and personal agendas amongst both politicians and top platform executives.

What we need are politically viable solutions. In the current environment, perhaps the only way to move forward is by taking common-sense, bipartisan steps that address the advertising business model. Big, radical, risky ideas are not likely to attract sufficient support, and we don't have the luxury of spending years in research-only mode. We need to move in parallel: careful, incremental regulations in tandem with more research to better understand the underlying problems and how to solve them in the longer term.

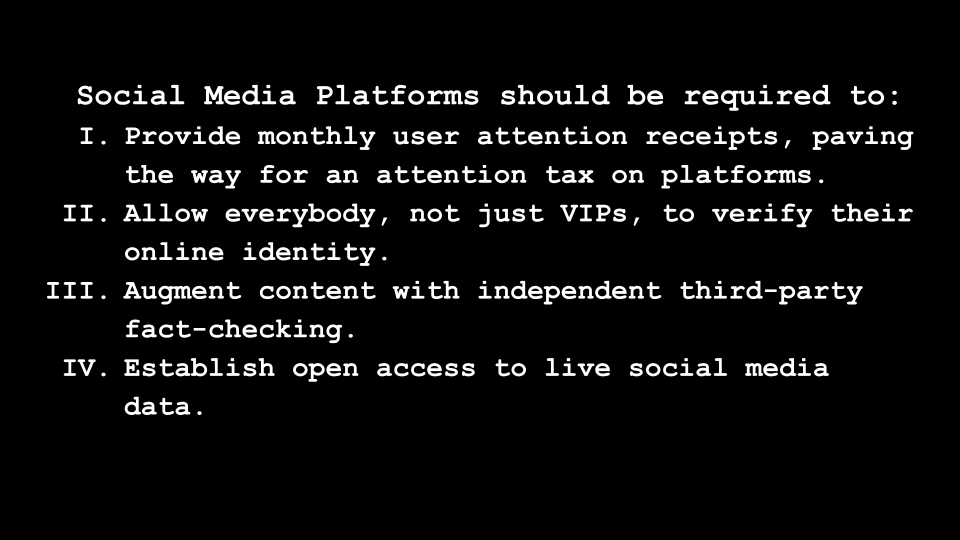

Below are three practical proposals regulators should urgently consider. These proposals (i) shift power away from the platforms toward users, (ii) increase transparency, (iii) do not take away any user rights that exist today, and (iv) are fully content-agnostic. Our suggestions aim to curb some of social media’s most harmful effects now, without foreclosing the adoption of more ambitious proposals further down the road.

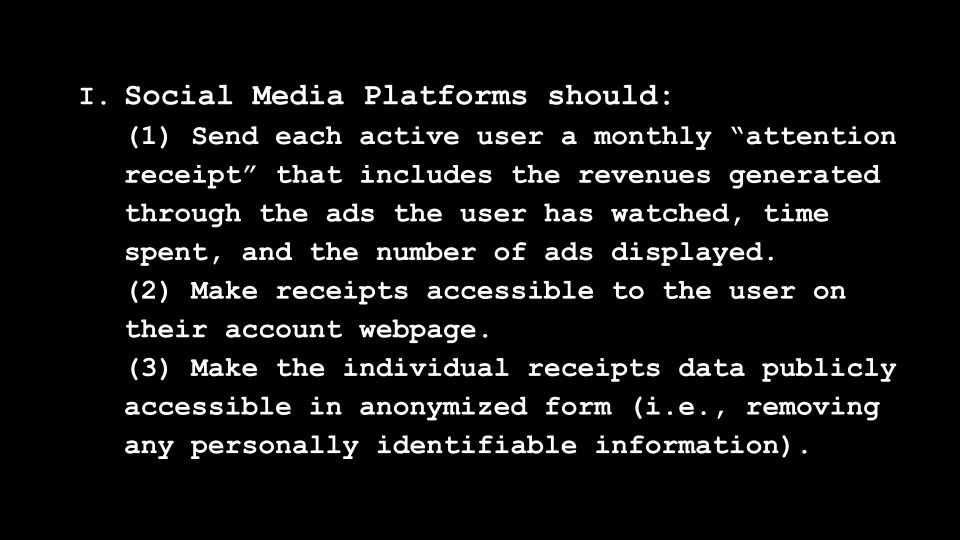

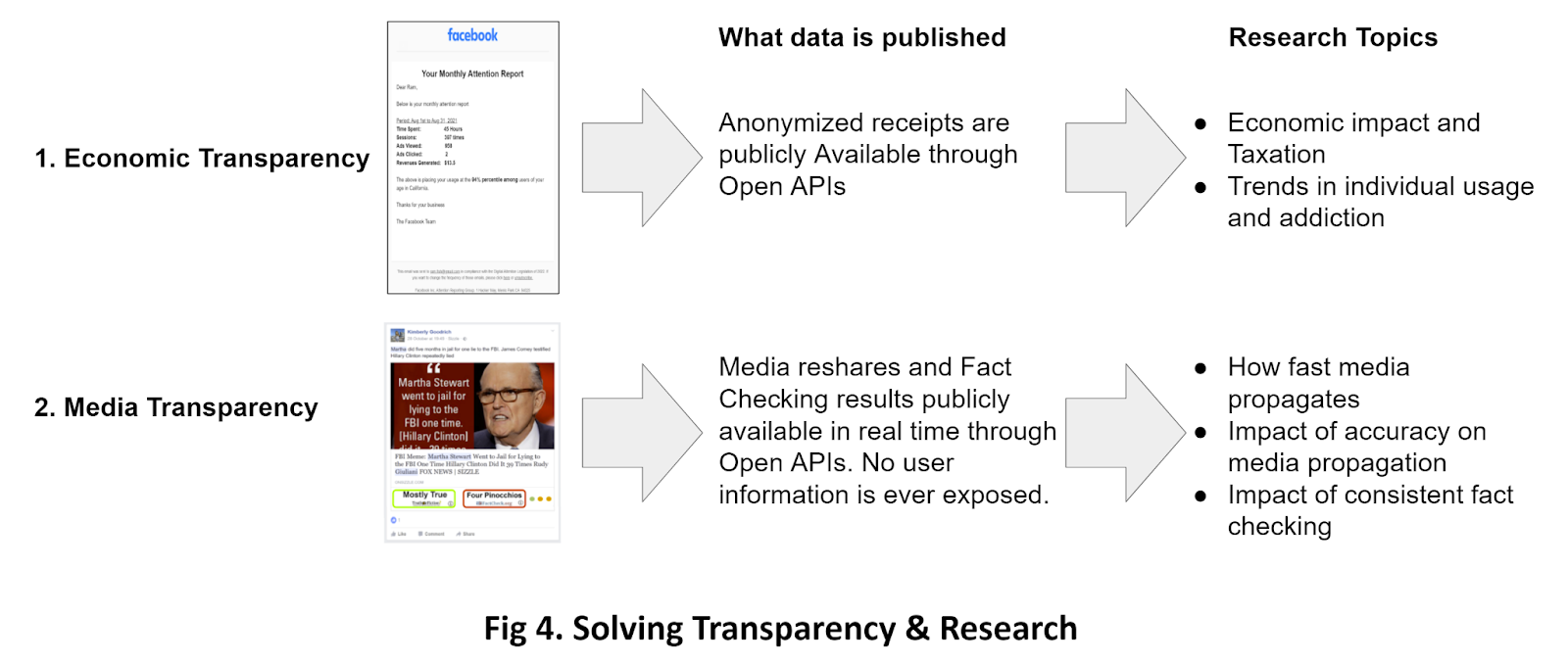

I. Provide monthly user “attention receipts,” paving the way for an attention tax on platforms.

In order to increase public awareness of the monetary value of user attention and the revenues it generates for the platforms and to pave the way toward eventually taxing that revenue, social media companies should be required to provide monthly attention reports for each user in the form of “attention receipts.” Such reports would provide users with a summary of time spent on the platform, how much money the platform earned from their attention, and their relative usage percentile each month. The platforms would also be required to make these figures publicly available in anonymized form. Such reports would generate data needed for regulators to research usage and develop new regulations while nudging some of the population to modify their usage habits.

We already mandate food and drug labeling as well as product warning signs. While evidence about the efficacy of these labels is mixed, this doesn’t mean we should move back to a world without labeling requirements. This rule would put social media on par with other industries that sell potentially harmful products.

Unlike information provided by other online time-tracking apps, attention receipts would directly link user time spent to platform revenue generated. This would help users understand in a more concrete way that they are paying for platform access with their attention. Other proposals have focused on the type and quantity of user data that websites can collect and store; this proposal focuses on making the platforms’ business model transparent at the level of the individual user. We should not expect receipts alone to transform user behavior, but they can help users better understand the trade-off they are making by spending time on platforms, as well as the platforms’ underlying business incentives.

Attention receipts might also be the first step toward an Attention Tax.Nobel Laureate economist Paul Romer proposed “A Tax That Could Fix Big Tech” in 2019, and a few U.S. states are already moving to put such a tax in place. Just like we use taxes to reduce pollution, smoking, or other negative externalities, governments can use such a tax to make it less lucrative to win users’ attention and nudge the platforms toward a healthier subscription model.

Would such a tax have a real impact on a company’s strategy? Due to the fact that public companies are valued using a multiplier on their earnings, a $1 reduction in earnings results in an approximately $25 reduction in corporate value. In the case of Facebook, a 10% tax on U.S. revenues would result in a $100B reduction in Facebook market capitalization. That is the kind of message shareholders hear; it may encourage the board and executive team to shift their revenue model away from advertisements and toward more subscription services, which are typically much more valued by investors. The tax should be progressive based on the platform’s overall ad revenues, which would encourage competition by new entrants.

Having a value assigned to our attention would also facilitate mandating access to paid, ad-free versions of the online services. As others have suggested, email, search, and social networks share many features with public utilities such as electricity or water—they have become 21st-century essential goods. The “attention receipts” proposal helps establish a monetary value for those services and paves the way for mandating that platforms offer a paid, ad-free subscription option. Shifting to a subscription-based business model would incentivize the platforms to develop and deploy feed algorithms that are not optimized to maximize attention, but that instead optimize overall user satisfaction. Getting the price for such a product right is crucial, and the data from the attention receipts is essential to determine the right number.

Yes, some people will always prefer a “free” version—but given the success of digital media products from companies such as Netflix, The New York Times, and other media companies that are increasing their paid subscriber base, it is possible to imagine a similar transition toward a paid social media subscriber model over time. One can also imagine using attention-tax revenues to subsidize wider access to subscription services.

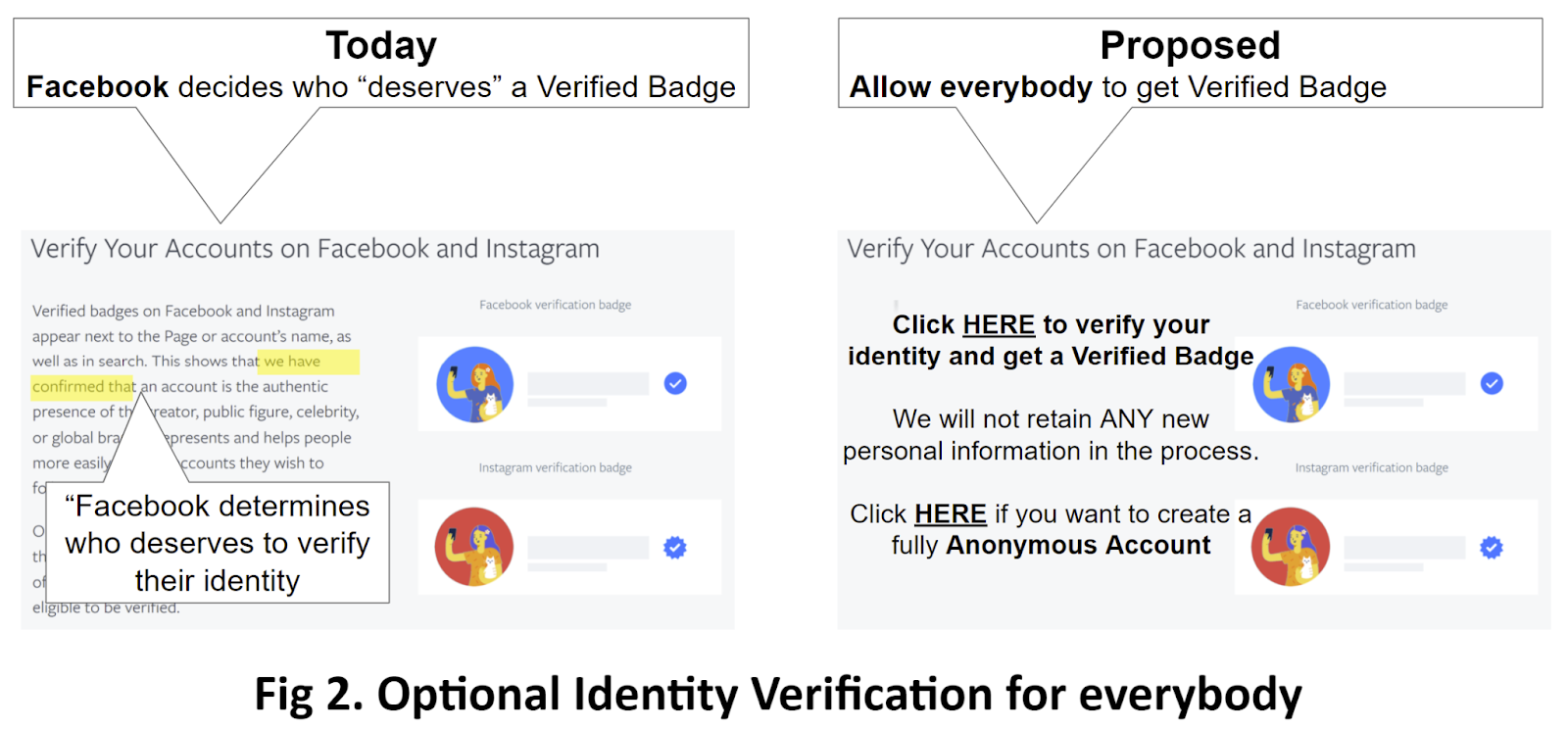

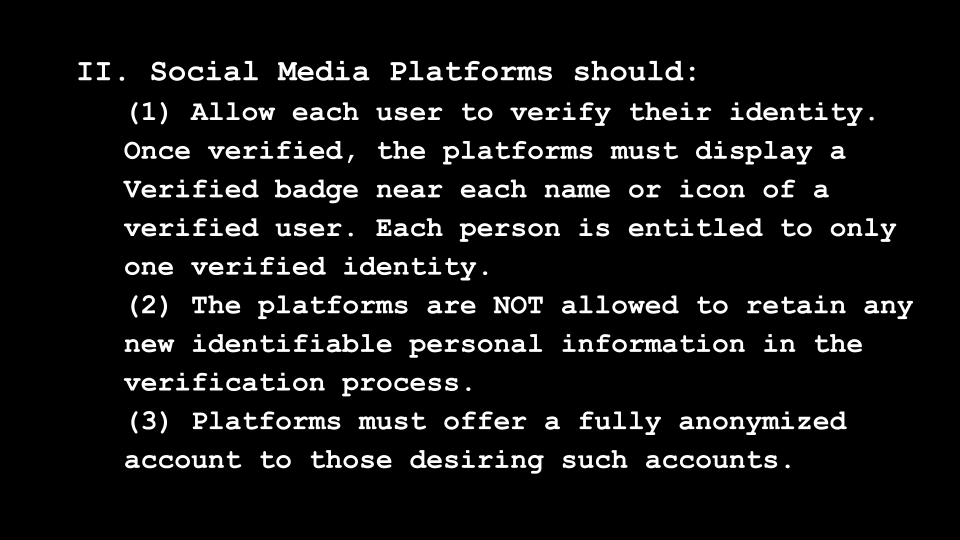

II. Allow everybody, not just VIPs, to verify their online identity.

Currently, Facebook and Twitter offer identity verification only to users the platformconsiders prominent enough to warrant it—such as politicians, celebrities and journalists. This rule would take this control away from the platforms and allow anyone to verify their identity and get the “verified identity” badge. Users could still have unverified accounts but would be limited to only one verified account per platform. To protect user privacy, the platforms would be prohibited from storing any new private information used for the verification (such as a driver’s license). At the same time, to preserve the individual right to anonymity, the platforms would be required to offer Truly Anonymous Accounts and prohibited from circumventing anonymity by linking anonymous accounts to any verified account. All of these ideas are based on how we govern physical communities--and bring the same principles to our virtual communities.

Anonymity has value for political dissidents and whistleblowers, but it also makes it easier for users to bully and harass others. Some of the toxicity in social media can be traced to the lack of self-restraint that anonymity enables—and this is a step forward in mitigating it.

Our proposal aims to allow whistleblowers and other users who might benefit from anonymity to preserve that option while taking away power from the platforms to decide who is entitled to seek verified status and giving the choice to users. We also hope this will bring back some civility into online conversations among strangers, and also reduce bots and fake accounts' political impact by making them easier to spot.

Content Neutral Dampers: Posts that encourage rage or hatred are the ones that are the most viral and quickest to be shared. Consequently, there are proposals for adding “circuit breakers” that slowdown how fast users posts and links to media can be amplified. Some suggest requiring that media content such as articles should be opened before they can be re-shared, and others suggest setting a maximum limit on the number of times a specific item can be re-shared by an individual.

“Verified Identity” opens an additional way to implement a content-neutral damper: Once we allow everybody to verify their identity, we have a new option for content-neutral dampers: Platforms could allow verified identities to reshare or retweet, but require unverified identities to publish original content or comment on other people’s content in order to amplify. This won’t address the problem of high-profile bad actors (who could be subject to de-platforming or amplification restrictions on other grounds), but it will cut down on amplification by bot networks or the “long tail” of users. As Renée DiResta has emphasized, freedom of speech doesn’t—and shouldn’t—mean freedom of reach.

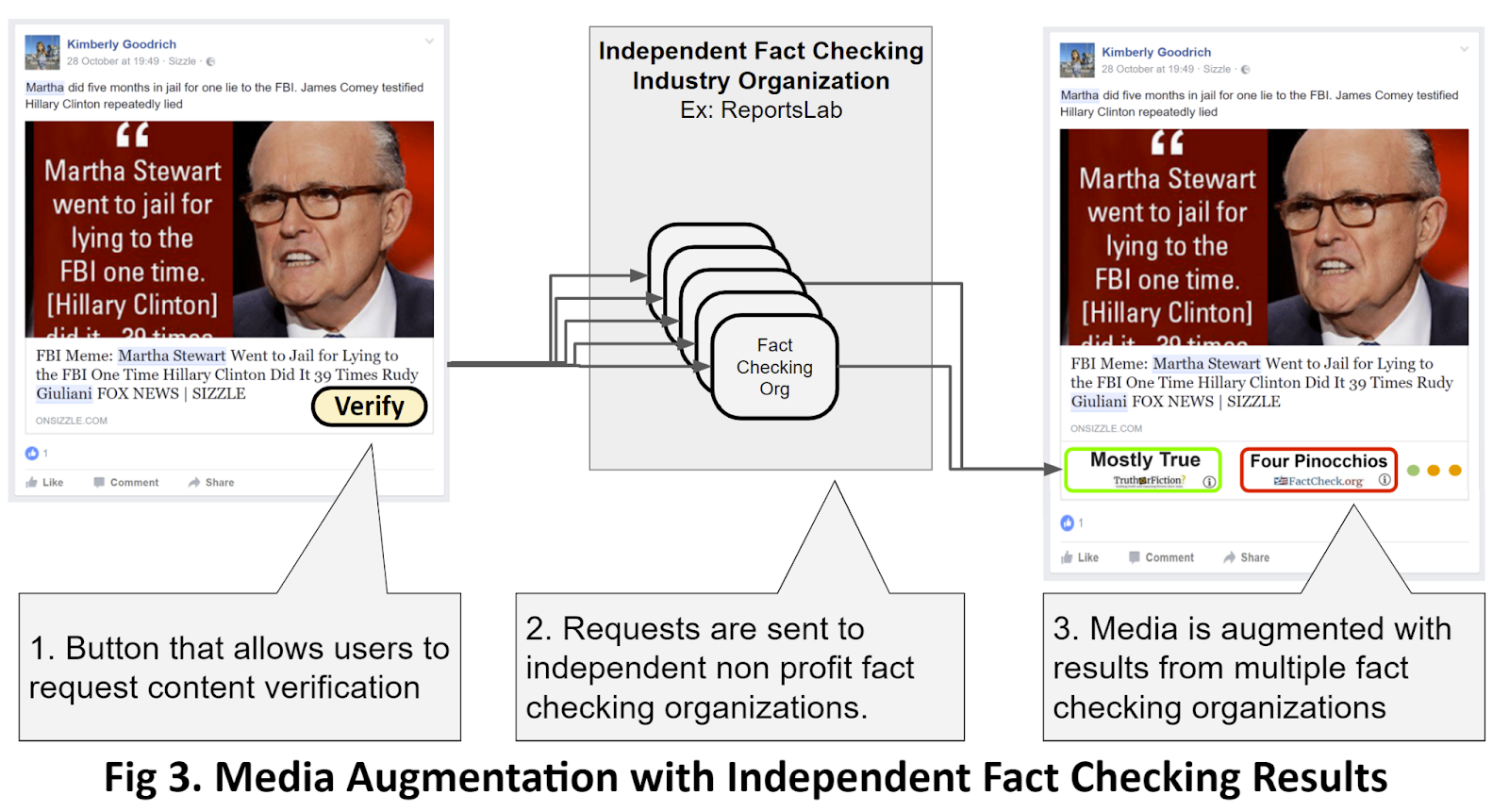

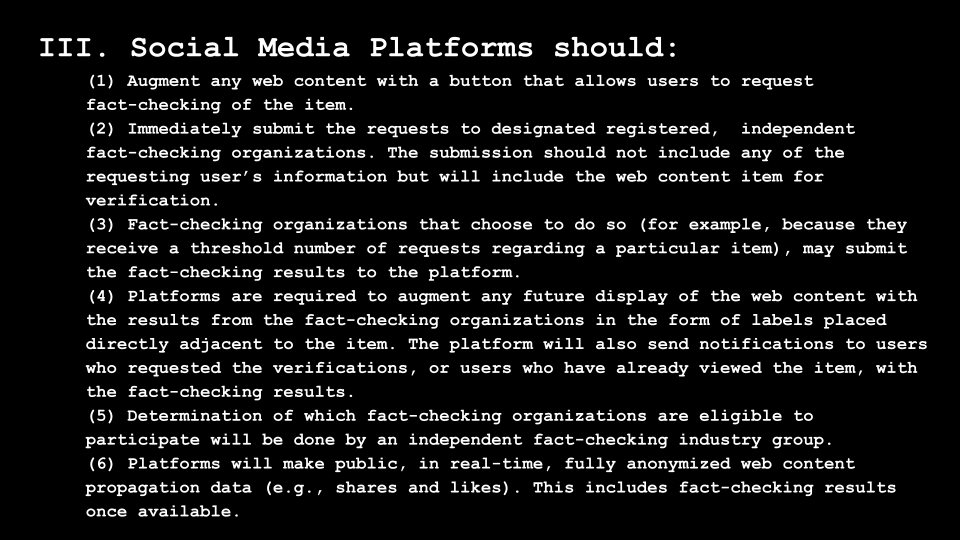

III. Augment public media with independent third-party fact-checking.

In the last ten years, the demand for fact-checking has grown exponentially. The number of fact-checking organizations has grown tenfold and consumers are learning to rely on and use fact-checking as part of their media consumption. This proposal builds on the thirst for fact-checking to add another “damper” that reduces the impact of fake, inciting, or misleading content that is currently amplified by the attention-driven business model.

Today, the platforms decide what to fact-check and what label or message to augment content with. This proposal would move the power away from the platforms and give it to the users and independent fact-checking organizations.

The platforms would rely on fact-checking organizations that are accredited by nonprofit fact-checking industry organizations such as the ReportersLab at Duke University or other similar organizations. These organizations are independent of government and platform control, set the fact-checking standards, and monitor the fact-checkers’ funding sources. These organizations can also leverage new crowdsourcing and AI fact-checking technologies.

Fact-checking’s positive impact extends to the content publishers and authors—the feedback loop encourages accountability. While some academics have found based on limited simulations that fact-checking is not effective in challenging pre-existing beliefs, other researchers show that fact-checking has a positive impact and does not “backfire.” Let common sense prevail: make it easy for users to ask for content-specific fact-checking, help bona fide fact-checkers do their job, and augment false or misleading content with clear labels.

Note that there is a fundamental difference between content augmentation—as outlined above—and “middleware filtering,” which has been promoted by some researchers and technologists. Content filtering is about allowing the platforms or other parties to remove content from a user’s feed—which should be the last resort (such as for child sexual abuse material or terrorist content). When filtering is applied more broadly as a content moderation strategy by third parties, it risks strengthening social media echo chambers and seems at greater odds with the values of free speech (and in the US, with the spirit of the First Amendment). Augmenting content is the opposite—it adds speech and aims to break down echo chambers by presenting users with analysis from different independent groups. Unlike reliance on filtering, augmenting media with fact-checking is more in the spirit of deliberative democracy.

IV. Establish open access to live social media data.

Both regulators and researchers have pointed out that transparency—having access to data so we can better analyze the problem and come up with a solution--is critical. The proposals above deliver on the transparency needed in a concrete, open way.

Specifically, we propose that the following data should be made publicly available:

- Anonymized attention receipt data, including dollars generated each month, time spent, zip code, and age group.

- Anonymized web content propagation data: real-time tracking of web content being re-shared, including available fact-checking results.

Making this information publicly available will enable research to be published and verified by other academics, which is more difficult in a closed model. This proposal also mandates anonymizing the data, so user privacy is fully protected.

Although platforms will likely protest, these types of data are not, and should not be considered, trade secrets or otherwise protected from disclosure. Like food labels, making this information public will reveal some of what the platforms do (thereby causing them minor harm), but doing so is good for consumers and good for researchers. It also opens the door for innovative services or apps to emerge, and helps level the competitive field.

---------

Summary: Nudging social media toward a more positive trajectory

With the above proposals in place, we can begin to imagine a social media experience where we are more likely to know if the posts we see are from a real human or not. We can get more timely feedback on the trustworthiness of posts we read. Our feed is less filled with provocations, as algorithms are increasingly optimized for us as users, not because our attention is the primary product being sold.

None of these proposals will “solve” the problem of social media harm entirely—because there is no one solution. But each of them can move the needle towards a world with a healthier social media environment and a better relationship between humans and technology.

Authors