Governments Want to Ease AI Regulation for Innovation, But Do Citizens Agree?

Natali Helberger, Sophie Morosoli, Nicolas Mattis, Laurens Naudts, Claes H. de Vreese / Jul 28, 2025

Meeting between Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, and JD Vance, Vice-President of the US, on the sidelines of the AI Action Summit in Paris, France, on Feb. 11, 2025. (Wikipedia Commons)

Not too long ago, governments around the world competed to be leaders in creating standards for the development and implementation of fair and responsible AI. In October, 2023, the Biden administration proudly announced an Executive Order that at the time it claimed "establishes new standards for AI safety and security, protects Americans’ privacy, advances equity and civil rights, stands up for consumers and workers, promotes innovation and competition, advances American leadership around the world, and more.” The order followed a very similar announcement by the European Commission, which had just launched “the first ever legal framework on AI, which addresses the risks of AI and positions European to play a leading role globally.” Meanwhile, the Canadian government concluded, “If Canada's advanced data economy is to thrive, it needs a corresponding framework to enable citizen trust, encourage responsible innovation, and remain interoperable with international markets.” Similar conversations on AI governance were held in other parts of the world, including Brazil, South Korea, Japan, and South Africa.

The case of the European Union is instructive. Only one year ago, the European Commission celebrated the adoption of the AI Act as a flagship initiative to realize its vision of human-centric and value-driven AI. The law was driven by the idea that by “developing a strong regulatory framework based on human rights and fundamental values, the EU can develop an AI ecosystem that benefits everyone.” One year later, the Commission’s AI Continent Action Plan signals a rather radical course change from developing an AI ecosystem that benefits everyone to a strong, competitive, and innovative AI ecosystem with gigafactories, data labs, AI innovators, start-ups, AI research, innovation hubs, and cutting-edge products and services as the key players. There is little left from the earlier emphasis on public values and fundamental rights.

Mentioned no less than 62 times in a 25-page document, the AI Continent Action Plan leaves little doubt that innovation is the new leading value of AI. The only references to fundamental rights or public values occur in relation to the AI Act. In the same document, however, the Commission also suggests that the AI Act must be simplified to ensure that its rules are ‘workable in practice.” Regulation is no longer seen as the driver but rather as an obstacle to the European AI ecosystem. Instead of a strong governance framework, the AI Continent Action Plan now refers to productivity, competitiveness, and tech sovereignty as the key drivers to “shape the future of AI and create a better tomorrow for all Europeans.”

The AI Continent Action Plan was accompanied by the European Commission’s announcement to revoke the AI liability directive, giving citizens legal rights against harmful AI, and the proposal for an Anti-Greenwashing Regulation. There are also rumors to cut back on, or even pause the enforcement of the AI Act, the DSA, and the DMA, fueling concerns that ‘simplification’ is synonymous with deregulation. The genesis of the AI Office’s Code of Practice for Generative AI providers, along with reports of preferential treatment towards the AI industry in the process, further suggests that the European Commission’s new vision industry is taking the lead in shaping what a ‘better tomorrow for all Europeans’ with AI will look like.

Partly, the rather radical change by the second Von der Leyen Commission can be explained by the relentless pressure on the European Commission from the new US administration under President Donald Trump and a handful of major technology companies. Indeed, in the US, Trump just unveiled a new AI action plan to “achieve global dominance in artificial intelligence.” Among other things, the AI action plan aims to gut regulation and introduce a moratorium on state AI laws (even though an earlier attempt to ban any AI regulation at the state level for the next 10 years as part of Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill was unsuccessful). However, within Europe, there is, and has always been, a strong tech lobby that prioritizes industry-led innovation. In this context, France and Germany increasingly push for a pro-business reset “for” Europe. Or, in the words of the Computer and Communications Industry Association, which is active in Europe and the UK: "Allowing competition to flourish in the AI market will be more beneficial to European consumers than additional regulation prematurely being imposed, which would only stifle innovation and hinder new entrants."

Conspicuously absent in the debate about regulation vs innovation are citizens. Again, the European AI Continent Strategy is instructive. Where citizens are mentioned (six times in total), this refers to the need to educate and upskill citizens to utilize AI effectively. After all, without users, the ambitious goals to enhance productivity and competitiveness or provide high-quality public services would remain rather theoretical. This raises an important question: Do citizens want regulation, and what do they expect from their governments? So, we asked them.

Citizens say they don’t want AI regulations watered down

To understand global preferences, we conducted a comparative survey in April 2025 across six continents. Partnering with Glocalities, we sent an online survey to citizens in Brazil, Denmark, Japan, the Netherlands, South Africa, and the US. A total of 6,961 individuals participated in the survey, with the data nationally representative based on age (18-70), gender, education level, and region. For analysis, the data was weighted to align with these quotas and adjust for varying sample sizes.

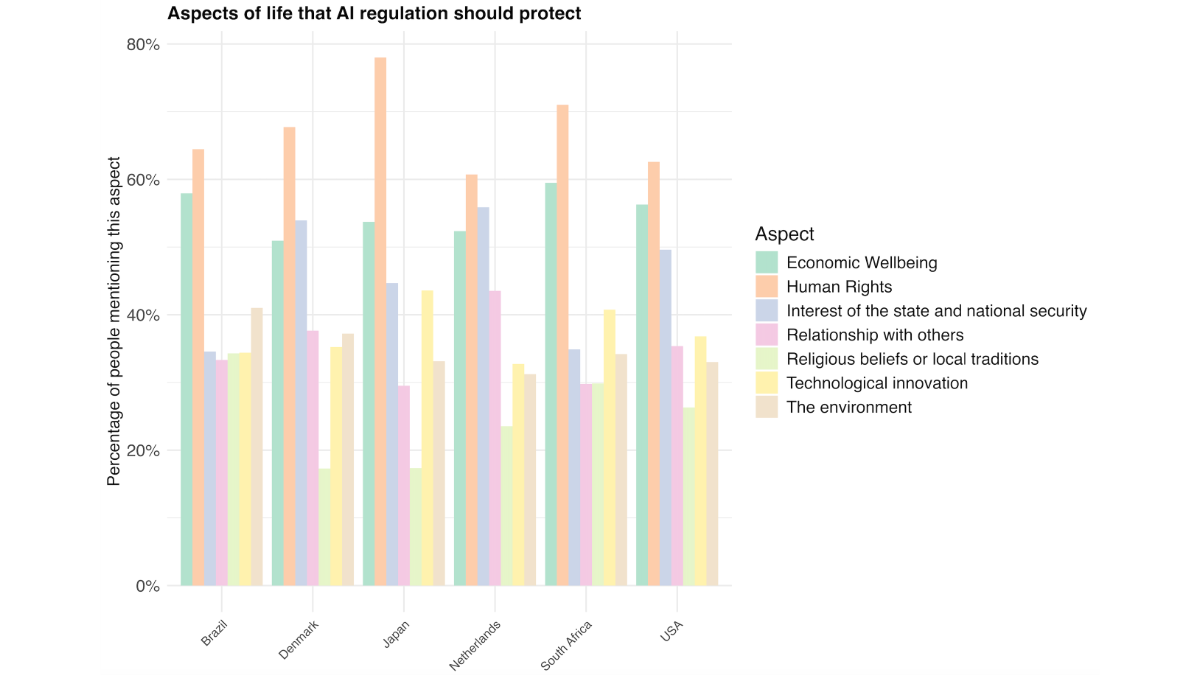

First and foremost, we were interested in which aspects of life citizens around the world deem most at risk from AI and should be legally protected (see Figure 1). Based on the survey results, it turns out that protection of human rights is seen as the most important priority across all countries, followed by economic well-being and national security. While there are some differences between countries, the overall trends are remarkably consistent across cultures and geographical regions (especially the desire to protect human rights above all else).

Figure 1. Aspects of life that AI regulation should protect per country. Respondents were asked the following: “Which aspects of life should AI regulation protect? Choose your top three aspects.” For details about the dataset, see the data note below.

Nonetheless, we also find some noteworthy country differences: citizens in Denmark and the Netherlands indicated that national security was more important to protect than economic well-being, whereas citizens in the other four countries prioritized economic well-being over national security. Religious beliefs and local traditions were overall the least mentioned when it came to the desire for AI regulation, but were notably more prominent in Brazil, South Africa, and the US.

The protection of technological innovation also played a significant role in many countries, most notably in Japan, South Africa, and the US. In Brazil, the environment played a central role, whereas in Denmark and the Netherlands, citizens would like to see regulation that prioritizes their relationships with others over environmental protection.

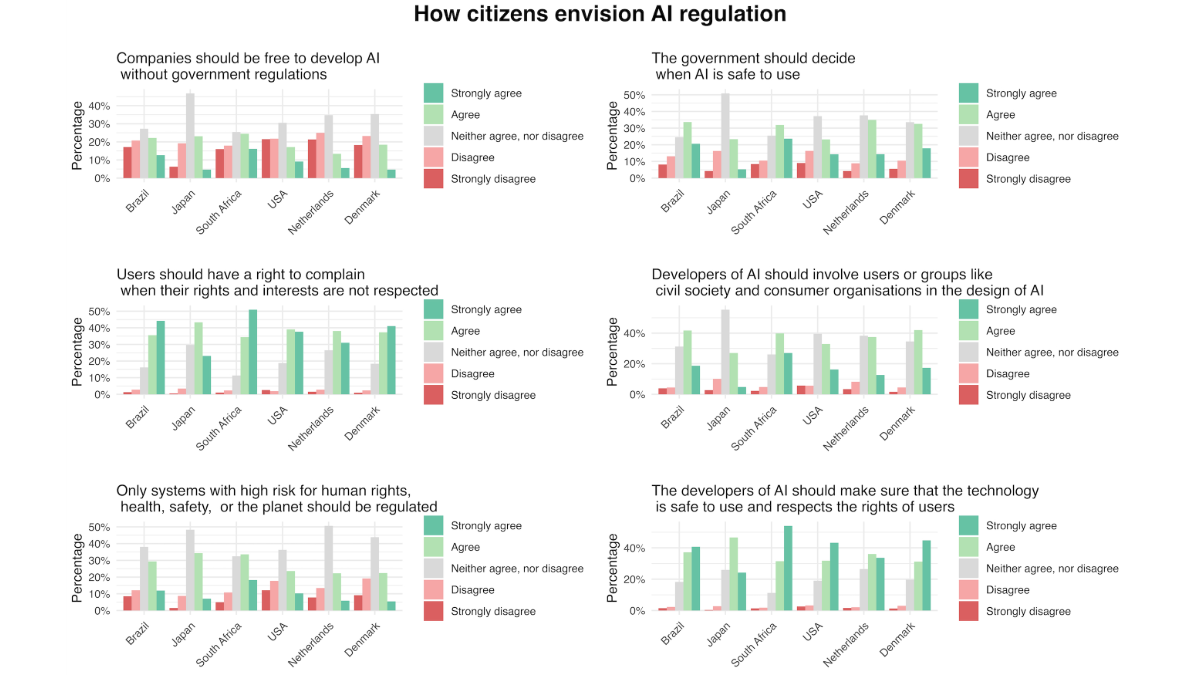

Secondly, we sought to understand how citizens envision AI regulation. For instance, who do they think should regulate AI and ensure its safe use? And what role do citizens believe they play in all this? Overall, we find that citizens across the six countries a) do not want that tech companies are free to develop AI without governmental restrictions; b) want the government to decide when AI is safe or unsafe c) citizens wish that only high-risk AI systems should be regulated d) and want developers to design AI that respects rights of users and is safe (see Figure 2).

When it comes to citizens' views on their role, the results show a strong consensus that users should have the right to complain if their rights and interests are not respected. They believe that developers should involve citizens in the design of AI. We find no notable country differences.

Figure 2. Regulatory preferences per country. Respondents were asked to what extent they agreed with six statements about AI regulation. For details about the dataset, see the data note.

Conclusion

The survey suggests citizens are not in favor of the recent push for deregulation and allowing AI innovation to progress unchecked. The findings from six countries show that the AI race is likely to play out at the expense of those most affected by it: citizens. Remarkably, not only Europeans but also US citizens who participated in the survey disagree with the idea that companies should be free to develop AI without government oversight. Instead, they want their governments to play a pivotal role in deciding when AI is safe to use. When asked which aspects of life AI regulation should prioritize, participants considered economic well-being and the protection of human rights more important than innovation. People also believe that AI developers have a major responsibility to ensure that AI is safe and respects fundamental rights.

Based on the survey, citizens are growing increasingly frustrated with being powerless spectators as the AI race unfolds. An overwhelming majority of citizens surveyed in Europe and the US alike want the right to complain when their rights and interests are not respected, and see users and user representatives actively involved in the design of AI. At the same time, many citizens expressed ambivalence about regulatory preferences, which shows that the conversation about AI regulation is far from over. Amidst all debates about innovation and AI transformation, tech developers and regulators alike forget that without demand and buy-in from citizens, the AI revolution will soon resemble Zuckerberg's Metaverse: huge investments and a race without an audience willing to buy a ticket.

Note: The survey data (N = 6961) was collected across six countries during April 2025: Japan, South Africa, Denmark, the Netherlands, Brazil and the U.S. The samples were nationally representative in terms of age, gender, education and geographic region.

How to cite the data: Morosoli, S., Naudts, L., Mattis, N., Helberger, N., Steen-Johnsen, K. & de Vreese, C. (June 2025). Cross-national Survey Study on AI and Journalism. Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Authors