India’s ‘AI Impact Summit’ Promises Little More Than Spectacle

Apar Gupta / Feb 15, 2026Apar Gupta is an advocate and founding director of the Internet Freedom Foundation. He is a 2026 Tech Policy Press fellow, and travels every other day on Mathura Road to reach the High Court and the Supreme Court.

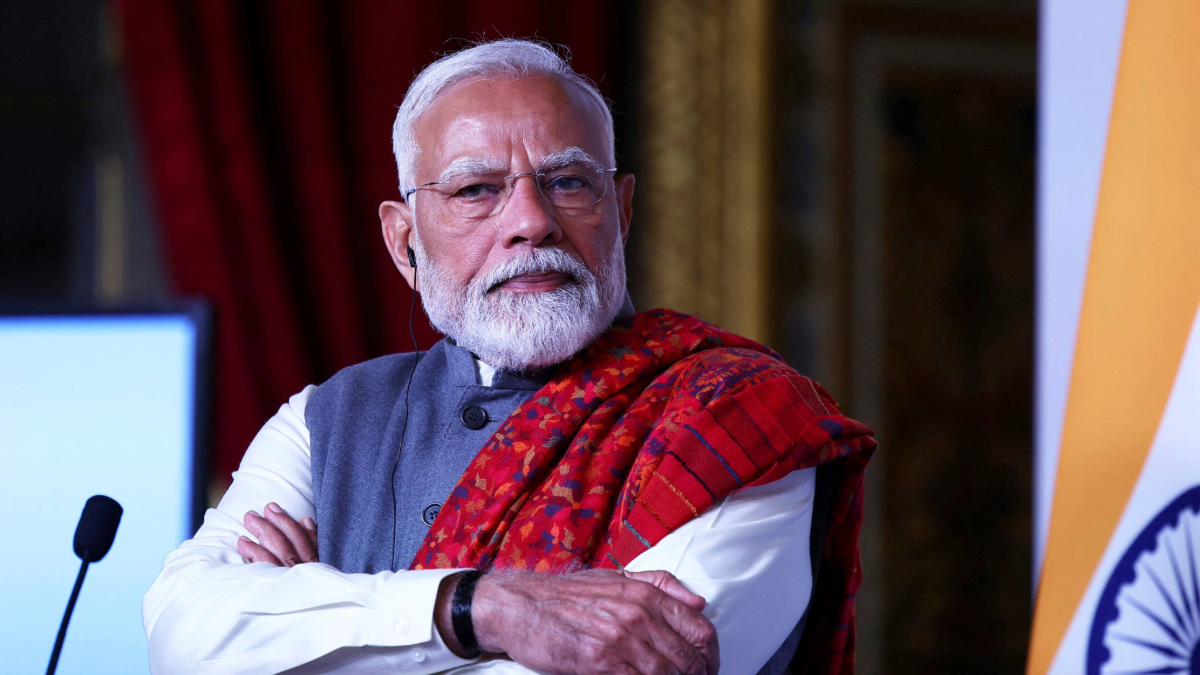

India Prime Minister Narendra Modi listens during the closing session of the Franco-Indian Economic Forum at the Quai d'Orsay on the sidelines of the Artificial Intelligence Action Summit in Paris, Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2025. (Abdul Saboor, Pool Photo via AP)

Over the past week, Mathura Road in New Delhi witnessed last minute repairs to further improve its aesthetics, and the homeless people residing along it were forcefully evicted. This cosmetic clean-up was prompted by the road serving as the primary transit path to the Bharat Mandapam complex, where India will host the AI Summit from February 16 that will last an entire week. The fourth in a series of convenings that kicked off in Bletchley Park in 2023, this installment is unique for being the first held in the Global South. But for India’s government, the event is also about optics and projecting Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a global leader while converting that image into domestic nationalist pride.

The summit's program, the goals for which were announced by Modi at the Paris AI Action Summit last year, is organized around three themes, called "sutras," that run through seven tracks, or "chakras." Of course, this classification or lexology does not emerge from pre-existing global AI policy frameworks. This choice of Sanskrit terminology is deliberate, aligning with a politics of cultural majoritarianism that closes the gap between official public communications and Vedic scripture. According to Vinayak Savarkar, the leading ideologue of the Hindu right, Sanskrit is “a sacred and a perfect language” that “contributes to national solidarity.” Matching this, the use of Sanskrit phrasing has become standard practice under twelve years of rule by the BJP-led NDA government within technology policy frameworks and legislation, which often rely on religious invocations rather than evidence or constitutional frameworks. These linguistic choices fit within a larger project of digital authoritarianism that, according to a recent joint report by the Center for the Study of Organized Hate (CSOH) and the Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF), includes various forms of coercion, surveillance, censorship and hate speech harming vulnerable and minority groups through the deployment of AI technology.

Official programming at the earlier summits in the series (Bletchley Park, Seoul, Paris) was compact by comparison to the India AI Summit, which is closer to a festival or large-scale exposition. While the summit intends to "democratize AI," an analysis of its 793 public events reveals the agenda setting power rests with the government (including aligned technical and academic institutions) and large technology companies. Government bodies dominate programming with central (e.g. MeitY, IndiaAI Mission, STPI) and state IT departments (Goa, Odisha, Telangana) involved in organizing approximately 40% of the sessions. Multinational corporations and industry associations command another 35%. This list includes Big Tech and AI startups along with chambers of commerce that serve both as sponsors and the intellectual architects for this event.

The corporate concentration is most visible in the "CEO Roundtable" and "Leaders' Plenary,” forums that, by their prominence, only throw into sharper relief the absence of any equivalent high-level platform for labor leaders, human rights defenders, or marginalized communities. There is no "Civil Society Plenary" with comparable prestige or access to heads of state. Viewed critically, the summit's structure grants multinational corporations parity with sovereign governments, normalizing a form of "multi-stakeholderism" where AI companies negotiate any potential governance rules directly with states. These misgivings are supported by a rough keyword analysis in which phrases such as, "Innovation," "Growth," "Efficiency," "Productivity," "Scale," and "Infrastructure" saturate the agenda. Human rights language is sparse and phrases such as, "Human Rights," "Accountability," "Exclusion," "Surveillance," "Bias," "Discrimination," and "Caste" are mostly absent from high-level plenary titles. What is omnipresent is the repeated presentation of the India AI Summit as an extension of the Prime Minister’s ‘vision’. The relatively sparse participation by Indian civil society also matches a trend in the closure of civic space in India, especially those groups and organizations that work in areas of human rights.

If we set aside the programming, even the planned outcome of a Leaders Declaration in the form of a "Delhi Statement" or "Delhi AI Resolution" offers little reason for optimism. Similar high-level events organized give us scant evidence that they translate to state practice, in regulation or norm building. For instance about two years ago with similar pomp and show India had organised the G20 Summit with a working group dedicated to the advocacy of its model of Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI). The adopted “G20 framework for systems of digital public infrastructure” identifies governance as one of the key three components for DPI, which in turn expressly comprises human rights and transparency commitments. With little regard for the words in this document and within this very timeline, after years of dithering, India enacted a contentious data protection law. It gives an unguided power to exempt the public sector, transparency activists agree it has ”fundamentally weakened” India’s right to information law and failed to provide a journalistic exception. The net effect of this is that pro-active disclosures or querying information on a DPI in India, or perhaps even reporting on it, is more difficult if not completely impossible. Moreover, India has already signaled a deregulatory and technocratic approach to AI technologies, and within such policy documents it has omitted mention of AI deployments in sensitive public sector uses, such as policing and welfare, where risks such as wrongful pretrial incarceration and denial of rations remain high and probable. Hence, it is only prudent to critically assess the value of any outcome document from this summit.

Finally, if the programming does not match the claims to “democratize AI” and well designed policy documents will not result in enforcement, then whose interests does this summit truly serve? Perhaps, if the Summit is viewed more pragmatically across the hundreds of events and the flood of emails and PDFs it will generate, it should be mostly understood as spectacle. Here, the slogan of AI providing “welfare for all, happiness for all” matches the massive scale of event organizing as a communications objective to produce narratives at volume. With Delhi hotel rooms touching $6,000 dollars a night, it is a reasonable forecast that the summit will prioritize the interests of power and profit, not only across the hundreds of panels and talks, but also in the deal making that will be done behind closed doors. This will be matched with a flurry of boastful digital content and news reporting on Modi, with leader and CEO-centric reels and photo moments.

Recognizing this reality does not discount the efforts of public officials, civil society, researchers and academic experts who are participating earnestly to advocate for rights respecting frameworks in AI. However, the very design of this summit and the overall context in which it is taking place may not value their intent or labor. Any claims of AI solving for population scale problems must be matched against the reality of the Global South, in which young boys were applying enamel paint on the railings in Mathura Road in peak morning traffic with their bare hands to prepare for the arrival of Silicon Valley CEOs.

Authors