India’s Courts and Legislature Fail to Rein in Speech Crackdown

Prateek Waghre / Sep 4, 2025Prateek Waghre is a fellow at Tech Policy Press.

The Mantralaya building, the administrative headquarters of the state government of Maharashtra in South Mumbai. Shutterstock

In an earlier piece on Tech Policy Press, I described how the executive branch in India uses a combination of “carrots and sticks” to shape speech and expression. As 2025 progresses, even as the executive branch continues to sharpen these proverbial sticks, some of its actions are being supported or enabled, wittingly and unwittingly, by institutions meant to act as safeguards against executive dominance — the legislative and judicial branches of government.

Legislative branch: ineffective, or enabler

A noticeable trend this year has been India’s state governments taking steps with adverse implications for the state of speech and expression in the country either by considering or enacting legislation, or through executive overreach. Another strand running through some of these developments is the invocation of moral stances and “ethos” as justification.

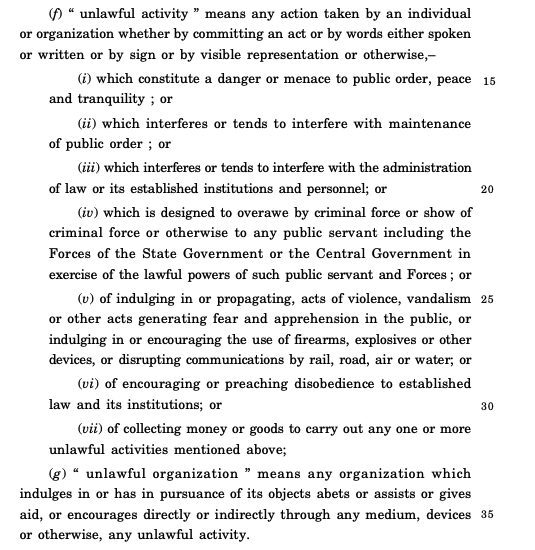

In July, the Maharashtra state assembly passed the Maharashtra Public Security Bill, 2024 purportedly to deal with, as per the report of the Joint Committee studying the bill, “urban naxalism.” Aakar Patel, chair of the Board of Amnesty International in India, notes that this term has no legal definition, but is, instead, a politically-charged phrase. The bill’s definition of “unlawful activity” (Image 1) is extremely broad, covering “any action taken by an individual or organization whether by committing an act or by words either spoken or written or by sign or by visible representation or otherwise,” that “interfere or tend to interfere” with administration of law or public order, or “encourag(e)… or preach… disobedience to established law and its institutions,” or fundraising for such and other listed activities. “(U)nlawful organization”, similarly, has an all-encompassing definition (Image 1). An editorial in The Hindu observes that these broad definitions allow it to target “anyone.” The bill includes fines ranging from INR 2 lakh to 5 lakh (~2300 USD to 5800 USD) and imprisonment terms up to 2 or 7 years based on what it deems to be differing levels of involvement with “unlawful activities” and “unlawful organizations.” Many of these are vague and leave a lot of discretion with law enforcement agencies.

Image 1: Definitions of "unlawful activity" and "unlawful organization" as per the Maharashtra Public Security Bill, 2024 as listed in the Report of the Joint Committee.

The bill, re-introduced in December 2024, was referred to a Joint Committee composed of 26 members from the state’s legislative assembly and council. Nearly 80 civil society organizations had written to the committee’s chair listing 18 concerns.

The committee’s report makes limited references to the risks associated with the over broad definitions, and does not address many of the concerns raised in the letter. It is worth noting that the committee did tweak some phrases to remove direct references to “individuals” in the title of the 2024 draft (but not in the definition of “unlawful activity”), and elevated rank requirements for police officers who could investigate offenses under it. However, this may be of little consequence when executive overreach is the norm.

The state government in Punjab, administered by the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), has proposed an “anti-sacrilege” bill (The Punjab Prevention of Offences Against Holy Scriptures Bill, 2025). A statement from the Chief Minister’s Office said that “(w)ith the enactment of this law, the State seeks to further strengthen the ethos of communal harmony, brotherhood, peace, and amity(.)“ The bill proposes a minimum prison sentence of 10 years (extendible to imprisonment for life) and fines in the range of INR 5 lakh to 10 lakh (~$5,800 to $11,500) for offenses defined as “ any sacrilege, damage, destruction, defacing, disfiguring, de-colouring, defiling, decomposing, burning, breaking or tearing of any Holy Scripture, or part thereof.” Abetment appears to carry the same penalty as the offense, while attempted offenses include prison terms of 3 to years, and a fine of up to INR 3 lakh (~$3,400).

For now, the bill has been referred to a Select Committee, reportedly after MLAs from the BJP and INC asked why feedback from legislators wasn’t sought, and indicated that more scrutiny was required. A group of around 80 civil servants belonging to the Constitutional Conduct Group has written to the chairperson of the Select Committee asking it to recommend its withdrawal, warning that it undermines the freedom of expression, enlarges the role of religion in matters of the state, and strengthens religious extremists. It remains to be seen whether the committee will recommend any significant changes to the present version of the bill.

On the other hand, committees may make recommendations that negatively impact freedom of speech and expression as well. The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Home Affairs, in its Two Hundred and Fifty Fourth Report on “Cyber Crime — Ramifications, Protection and Prevention,” recommended a review of India’s safe harbor provisions on the basis that intermediaries have not complied with requests for “removal of online unlawful content.” However, recent reportage based on disclosures in court as part of the social media platform X’s lawsuit against the Government of India has demonstrated that law enforcement agencies tend to interpret what is “unlawful” in very broad terms, resulting in arbitrary and selective enforcement and censorship. Other government bodies, such as the Department of Railways, are aboard this train, too.

The wide-ranging report also covered streaming platforms, noting that they have become the “primary source of entertainment.” It drew parallels with the pre-release certification system for films by the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), colloquially called “the censor board.” The board’s function has always been controversial, but questionable actions are now more common. Saurav Das, an independent journalist and RTI activist, has described it as a “moral tribunal.” The committee recommends that a “Post Release Review Panel” should devise “suitable norms and guidelines keeping in view the cultural ethos and sensitivity of the country.” It also recommended that this panel monitor “flagged or trending content” based on user complaints — potentially a recipe for moral policing and informal pressure. This panel may also be tasked with deciding penalties for violation of norms/guidelines, although it wasn’t clear if this was meant to be a case-by-case adjudication or the establishment of a framework for penalties. Directionally, some of these recommendations resemble the Broadcasting Services (Regulation) Bill (Broadcasting Bill). Dissent notes by INC MPs Ajay Maken (pgs. 117, 119) and Priyanka Gandhi Vadra (pg. 125) suggest that a draft version of the report envisioned a pre-certification mechanism for content on streaming platforms which could have effectively been a “censor board” for other forms of content. Earlier in the year, the Standing Committee on Communications and Information Technology had also pushed for action on the problematic Broadcasting Bill.

This is a limited set of examples, but together they demonstrate that the mechanisms afforded to the legislative branch, both at the level of the union and state governments, are currently proving to be insufficient to impose meaningful limits on the executive branch.

The Judiciary: an unreliable and inconsistent defender

The judiciary may not always see eye to eye with the executive, but on matters concerning citizens’ speech its recent record is checkered, and directionally worrisome. Even in cases where an individual may be protected or granted relief, courts, either through oral remarks or directions to governments, pave the way for developments that are likely to have negative consequences in the long run.

Since I last wrote about the case of Prof. Ali Khan Mahmudabad, prosecuted for his Facebook posts on Operation Sindhoor, India’s recent campaign against Pakistan following terror attacks in Kashmir, the Supreme Court has changed its demeanor, restricting the Special Investigation Team (SIT) from repeatedly summoning him, reiterating that its investigation be limited to the First Information Reports (FIRs) in the 2 cases against him, and even directing a trial court not to frame charges based on a charge sheet (criminal complaint). Yet, its role in extending the ordeal for Mr. Mahmudabad cannot be denied given its directions to constitute the SIT in the first place.

There wasn’t a noticeable shift in the Supreme Court’s posture in cases related to India’s ‘Got Latent’ crass humor, however (I wrote about one of them in its early stages here). In late August, a two-judge Supreme Court bench argued that a different standard of speech protections apply to speech for commercial purposes. While there is room for a broader conversation on how commercial motivations may shape incentives, it is not clear how the court seeks to arrive at this standard.

The court went further, asking the government to regulate content creators’/influencers’ speech on social media. This particular case was to do with comments made about persons with disabilities, but one should expect, given the context and history with the Broadcasting Bill, that any such regulation will be broader in scope and intent.

This is not surprising, as the court alluded to this multiple times during earlier hearings in this case, and, in other cases, too.

In mid-July, a different bench of the Supreme Court, hearing an anticipatory bail plea by cartoonist Hemant Malviya for a cartoon lampooning India’s Prime Minster and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), remarked that the court “will have to do something about this,” and even referred to guidelines about posting on social media. Malviya also had to apologize and delete the post in question. The original complaint was based on an edited version of a cartoon that Malviya made in 2021. As per AltNews, he reshared the edited version on Facebook. The High Court of Madhya Pradesh, which denied his bail plea, stated that he had overstepped the threshold of freedom of speech and expression and “does not appear to know his limits.”

Around the same time, in another bail plea filed by Wajahat Khan, a bench of the Supreme Court spoke about the importance of citizens valuing the freedom of speech and expression, and that if self-restraint on social media wasn’t exercised, the state would have to intervene. Unfortunately, this wasn’t limited to being a cautionary note, instead, the court went on to raise the question of why there aren’t guidelines for citizens, and possibly sought the intervention of the state in doing so.

In early August, while hearing a petition by the Leader of Opposition in the Lok Sabha, Rahul Gandhi, against a criminal defamation case for his remarks on the Galwan clash between armed forces from India and China, one of the justices questioned Gandhi and said that he would not have said it if he was a “true Indian.” The bench responded to a comment by Gandhi’s counsel, asking why these statements were made on social media and not in the Parliament. The court did temporarily stay proceedings against him.

In each of these cases, individual relief, even if temporary, was granted. However, in the process, courts adopted a paternalistic, and sometimes antagonistic, tone towards petitioners, and opened the doors to or explicitly invited the state to arbitrarily intervene in matters of speech — ultimately strengthening the executive branch. And, in most of these cases, a high court refused to provide relief, necessitating the need to go to the Supreme Court in the first place.

Further compromised institutions?

The inability of the legislative and judicial branches to restrain executive overreach must also be viewed in the context of some of their own systemic failures.

State legislatures are functioning a mere 20 days on average throughout the year, as of 2024, while in the union parliament norms and procedures are routinely set aside for cloak-and-dagger techniques such as introducing bills with limited/no advance notice and then pushing them through parliament with minimal discussion. For example, The Promotion and Regulation of Online Gaming Bill went from something few seemed to know about to receiving presidential assent in 96 hours. The judiciary may not always be directly aligned with the union government as was evident in its decision to impose restrictions on how long governors could withhold their assent for bills, a practice being used to effectively veto them. However, its tendency to indulge the executive/prosecution leads to outcomes inconsistent with its role as a defender of citizens’ rights, especially in cases where human liberties are at stake.

The end result? A more dominant executive with the ability to further compromise fourth branch institutions and watchdogs.

Authors