Optics and Opacity: Breaking Down Meta’s Refusal to Suspend Hun Sen

Daron Tan / Sep 20, 2023Daron Tan leads the International Commission of Jurists' (ICJ) work on digital rights and internet freedom in the Asia-Pacific.

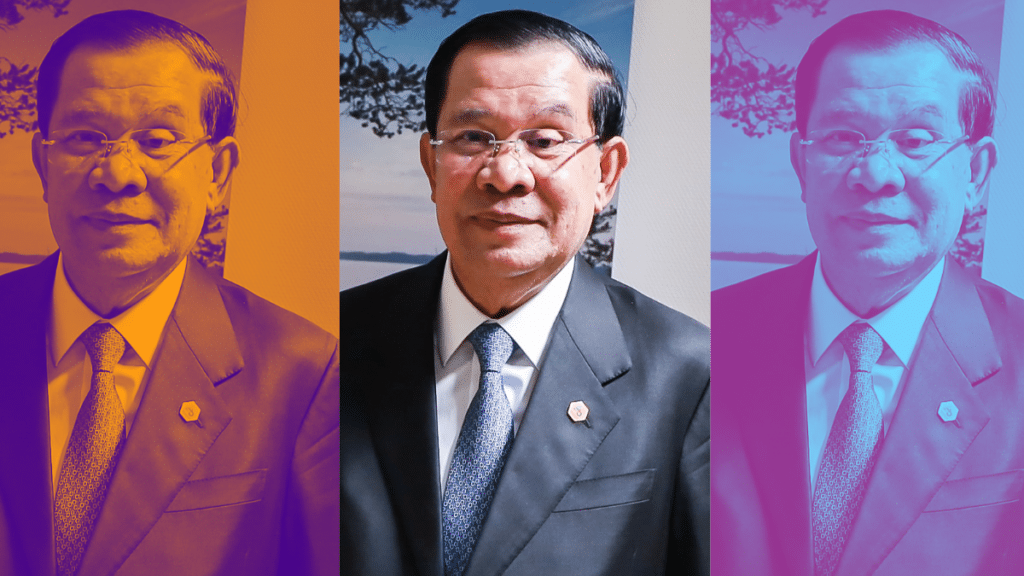

On January 9, 2023, former Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen posted a video on Facebook where he threatened his political opponents with violence, which was escalated to Meta’s Oversight Board for its consideration. My organization, the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), submitted a public comment to the Board on the case, highlighting the ongoing violence and crackdown by the authorities against perceived political opponents in Cambodia and the real risk of further human rights abuses and other harms if Meta did not take action.

The Oversight Board agreed and issued several recommendations, including that Meta suspend Hun Sen’s Facebook page and Instagram account for six months. However, Meta rejected several of the Board’s recommendations, including the recommendation to suspend the accounts, explaining that “suspending those accounts outside our regular enforcement framework would not be consistent with our policies, including our protocol on restricting accounts of public figures during civil unrest.”

Confused after reading Meta’s response? Me too. Meta’s explanations are perplexing and peppered with jargonistic references to its different policies. In essence, what Meta is saying (or at least, from what I understand) is:

- Meta does not think that Cambodia was/is in a situation of crisis under its so-called Crisis Policy Protocol. Thus, the company’s policy on restricting accounts of public figures during civil unrest will not apply.

- Using Meta’s ordinary rules, there is no basis to suspend Hun Sen’s account.

- Meta also refused to update the policy on public figures and civil unrest such that it may apply to Cambodia, where there is a long history of state violence and human rights violations. According to Meta, applying the policy to these situations could lead to indefinite suspensions for public figures.

Meta’s decision has drawn sharp rebuke from human rights groups. For instance, colleagues at Access Now underscored that Meta’s decision “sends a dangerous signal that [Hun Sen’s] rights-abusing speech will be tolerated on its platforms.”

I share these sentiments. Meta’s decision creates the expectation that there will be no accountability for Hun Sen’s longstanding abuse of Meta’s platforms to threaten and incite violence against his real or perceived opponents. Meta has indicated that continued violations of its policies will result in restrictions, but what about the abuse that has already occurred?

Meta’s decision ultimately points to a fundamental issue of how its rules are, in the first place, constructed with overly expansive language, granting Meta significant latitude to do as they please on an ad hoc basis, unencumbered by consistent application of normative constraints. Furthermore, this decision illustrates how the enforcement of Meta’s Community Standards is, like in many other instances, shrouded in secrecy.

De facto impunity for sustained human rights violations

Meta’s decision now creates two separate enforcement regimes for when a public figure incites or threatens violence online. If this happens during what Meta considers to be a situation of sudden civil unrest and violence, Meta may restrict accounts for longer periods of time. However, if this has been going on for an “indeterminate period of time” – which, arguably, makes the situation far more serious than a one-off instance of violence – then Meta’s ordinary rules apply, with a far laxer restriction framework (e.g., ten or more strikes will result in a 30-day restriction). Is Meta effectively encouraging authoritarian regimes to engage in a “history of state violence or human rights restrictions” for an “indeterminate period of time” by allowing them to escape suspension?

In applying Meta’s ordinary penalty framework, it is not apparent why Hun Sen’s repeated violations have not attracted stricter sanctions beyond just removing the January 9 video, irrespective of whether suspension might be deemed a disproportionate and unnecessary measure. Hun Sen’s January 9 video that threatens and incites violence clearly should qualify as violating Meta’s “more severe policies” and attract stricter penalties. The violation should be seen as one of particular egregiousness given that it was not an isolated incident: the Oversight Board’s decision noted at least four instances of content being posted on Meta’s platforms containing threats, including threats of violence. It was also reported that Hun Sen reposted the January 9 video, which Meta removed but without “any visible repercussions.” Evidence suggests these violations resulted in offline physical violence.

Meta claimed that it applied “appropriate account-level penalties associated with that action.” Still, we have no idea what these penalties are and how they may be proportionate sanctions for Hun Sen’s actions. Optics matter, and this failure to explain the penalties, assuming there were any, has contributed to the impression that prominent figures using Meta’s platforms to threaten and incite violence will enjoy impunity and face no consequences for their conduct. Critically, without public knowledge of the penalties, what should be a main function of Meta’s regulatory regime, i.e., deterrence of such misconduct on its platforms, is effectively nullified.

Opaque enforcement and design of Meta’s rules

Meta’s decision also demonstrates a broader pattern of a lack of transparency in enforcing its rules. We do not know what “appropriate account-level penalties,” if any, have been imposed on Hun Sen and the reasoning behind them. We do not know why there is “currently not any basis to suspend Hun Sen’s account under [Meta’s] policies.” We do not know why and how Meta determined that Cambodia did not meet the “entry criteria threshold for crisis designation,” despite the multitude of submissions pointing in the opposite direction, including in the Board’s decision and the ICJ’s public comment to the Board.

The arbitrariness in Meta’s enforcement of its rules is directly linked with how the design of the rules themselves are overbroad and ambiguous, thus granting significant discretion when making decisions. These concerns extend to the ordinary enforcement framework, its newer policies on public figures and civil unrest, and its Crisis Policy Protocol. Ironically, the latter were updated in response to the case on former President Trump’s suspension from Facebook and were presumably aimed at introducing further transparency and consistency.

It is a general principle of law, known as the principle of legality, that rules must be formulated with sufficient precision in order to not grant unfettered discretion to those charged with their implementation – a principle that Meta’s rules patently fail to conform with. For instance, what are considered Meta’s “more severe policies” under its ordinary penalty regime? How is the risk of “imminent harm” under its Crisis Policy Protocol assessed, and what other factors determine what constitutes a crisis?

It is hard not to conclude that the jargon contained in these policies is being used as ex post facto justifications and conceptual smokescreens for inconsistent and opaque decisions.

The newsworthiness allowance

However, not all hope is lost, as Meta is still mulling over the feasibility of the Board’s recommendation to clearly state that “content that directly incites violence is not eligible for a newsworthiness allowance, subject to existing policy exceptions.” The ICJ had made an identical call in our public comment, in line with article 20(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which requires the prohibition of incitement to violence, hostility, or discrimination.

At present, Meta’s newsworthiness allowance currently allows Meta to keep offensive content that violates its rules if it decides that the public interest value of keeping the content outweighs the risk of harm. This allowance was also a central tenet of the Board’s case, as Meta had been unsure whether Hun Sen’s violent speech should qualify as “newsworthy” and thus be left up.

It bears repeating that one of the very few limitations that is mandatory under international human rights law is the prohibition of incitement to violence. Meta’s current newsworthiness allowance allows for a loophole in this prohibition, which is, as above, exacerbated by the ambiguity and opacity in which the policy is currently constructed and enforced. If not applied with additional protections, this allowance would eviscerate the protection provided by human rights law against expression inciting violence. Meta’s decision to reject the Board’s recommendations to clarify its policy on public figures sets a dangerous precedent going forward.

However, there is still an opportunity for it to at least take some positive steps towards abiding by its human rights responsibility to respect human rights, in line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, by revising its newsworthiness allowance in line with human rights law and standards. Having an unequivocal carve-out to its newsworthiness allowance for incitement to violence would at least allow Meta to be consistent when adjudicating similar violent content in the future, even if the rest of its rules and standards leave much to be desired.

Authors