Overcoming Fear and Frustration with the Kids Online Safety Act

John Perrino, Jennifer King / Nov 13, 2023John Perrino is a policy analyst at the Stanford Internet Observatory. Dr. Jennifer King is the Privacy and Data Policy Fellow at the Stanford University Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence.

The Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) has bipartisan support from nearly half the Senate and the enthusiastic backing of President Joe Biden, but opponents fear the bill would cause more harm than good for children and the internet.

Last week, we heard new promises to bring KOSA and other bills addressing children's safety to a floor vote after a second Facebook whistleblower testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee with yet more details of how Meta leadership ignored evidence that Instagram was harming teens.

The bill was updated and passed unanimously out of committee in late July, but civil liberties groups continue to raise concerns about privacy issues with age-based measures and “duty of care” requirements that could empower state attorneys general to file lawsuits prosecuting culture war issues, such as content recommendations related to gender identity and abortion.

Related: Read more perspectives on KOSA

For parents and youth advocates, there is an obvious and urgent need to regulate the design of social media and similar online platforms. Many young people and parents know someone who has struggled with social media use and want technology companies to be held accountable. Teens have a complicated relationship with social media and parents are understandably concerned with declining youth mental health and wellbeing.

One thing both sides in the battle over KOSA have in common? Fear and frustration that it might not be possible for Congress to pass any legislation on social media privacy or safety.

Unfortunately, the fate of the legislation may come down to a fight that is rife in emotion, but lacking in nuance or a clear path forward.

Critics cannot entirely dismiss KOSA, and advocates must recognize that online safety legislation requires a remarkably difficult Goldilocks balance to get the rules just right. Clear, yet adaptable. Protective, but unobtrusive. All with empowerment and authority for children and parents that does not prevent access to online spaces or inhibit free expression.

Advocacy is essential, but KOSA will not move forward without compromise. Some steps have been taken to address concerns, but more needs to be done. We need adults (and young people) in the room who are willing to find consensus and take action.

What’s in KOSA and Recent Changes

While the debate has focused on a few key components of KOSA, there is a lot more in the bill, and most of it is uncontroversial. Recent changes also lessen requirements for age verification in response to privacy concerns and the potential for parental abuse.

The bill would set a duty of care to protect children under 17 on social media and similar online spaces — such as video games, virtual reality worlds, and online messaging or video chat spaces that connect strangers. The duty of care is specific to addressing mental health disorders, compulsive usage, sexual exploitation, the promotion of drugs or controlled substances, deceptive marketing, and violence, bullying, or harassment.

The law would require that platforms provide safeguards for young users and strong default privacy protections, including the ability to limit who can contact them and to set time limits. Parental control tools would be required to manage privacy and account settings, view and restrict app usage, and restrict in-app purchases. Smaller services could utilize integrations with the parental control settings on a user’s device.

The bill would set deadlines for responses to user reports of harm to children and require a reporting system accessible to parents, minors, and schools. Transparency and research measures would require companies to conduct safety audits and make more information available to the public and some academics.

KOSA would spur government research on age verification measures, set rules for research conducted by social media companies on young users, and create a Kids Online Safety Council with diverse representation from government, civil society, and academia. KOSA would also restrict targeted advertising for young users.

Most measures would apply to social platforms regardless of revenue or user numbers. This wide scope is targeted at small but significant platforms for teen users that facilitate anonymous interactions or connections with strangers. It also is meant to ensure that online social spaces in virtual worlds or video games popular with teens are covered.

KOSA does not cover text messaging, email, online video or audio calls, blogs, or other spaces without content or real-time interaction with strangers.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and state attorneys general have authority to enforce most of the requirements in the bill.

Recent Changes in the July Markup

The bill was updated and passed unanimously out of committee in late July with a few noteworthy changes.

Compliance with age-based restrictions now uses an “objective knowledge standard,” which means that companies would not need to take new measures to obtain the age of users. This is an attempt to address privacy concerns with existing age verification techniques.

Parental consent measures have been replaced with language requiring “a parent’s express affirmative acknowledgment” for users under 13 to create social media accounts with safeguards and parental control settings.

A research program on the effects of social media on youth, previously open to most independent researchers at nonprofit or academic institutions, would now be conducted by contracting the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. The previous measure faced industry opposition and conservative pushback related to concerns about censorship, according to multiple sources familiar with the negotiations.

The amended bill refers to a current National Academy committee on the Assessment of the Impact of Social Media on the Health and Wellbeing of Adolescents and Children. Stanford Internet Observatory Faculty Director Jeff Hancock is a member of that committee, which is expected to release a report later this year.

Major Debates

Much of the concern with the bill comes from reading between the lines with fears about how the legislation would be enforced or used to advance political agendas.

Civil society and industry groups oppose the legislation due to concerns it would advance political culture wars. They also raise fears about privacy, safety and security risks in a future internet where age verification would be required to access information.

These debates are focused on the interpretation and enforcement of the duty of care provision, age-based restrictions, and potential abuse of parental control requirements. Hyperbole abounds, and there is a seed of truth in some concerns. This makes it difficult to sort fact from fiction about the bill.

A Duty of Care and Transgender or Reproductive Health Content

The duty of care in KOSA has a substantially more detailed and narrowly tailored set of requirements than past state legislative attempts, but critics still argue the legislation would incentivize platforms to limit politically controversial content available to young users in violation of legal rights to free expression.

This is the most important and difficult section of the bill to get right. A duty of care must find the right balance to address design without targeting content. If done successfully, a duty of care could hold social media companies accountable for compulsive usage and awful harms, such as sexual exploitation, while protecting First Amendment rights to include legal but controversial content about topics such as reproductive health or gender identity in teen users’ feeds.

The rules do not apply to search results and permit users to access information from clinical or other authoritative sources. This wording seeks to address that the duty of care could be used to restrict access to information about gender identity or reproductive health. At the same time, it inherently acknowledges that the duty of care is both about design and content.

The bill gives state attorneys general broad power to interpret harmful content and file suit against social media companies for failing to filter certain content from children. While access to “clinical resources” is protected under the bill’s definition of a duty of care, it is clear that state attorneys general plan to file suit regardless.

State attorneys general have political incentives to bring new lawsuits against Big Tech, using KOSA to target transgender content and continue their legal war against Big Tech. The question is whether those opposed to that action are confident the duty of care is sufficiently narrow to ensure successful enforcement in the courts addresses real design harms.

Supporters note that the duty of care is tailored to only cover specific harms facilitated by the design of many social media companies. The challenge lies where algorithmic recommendations push inappropriate or potentially harmful content.

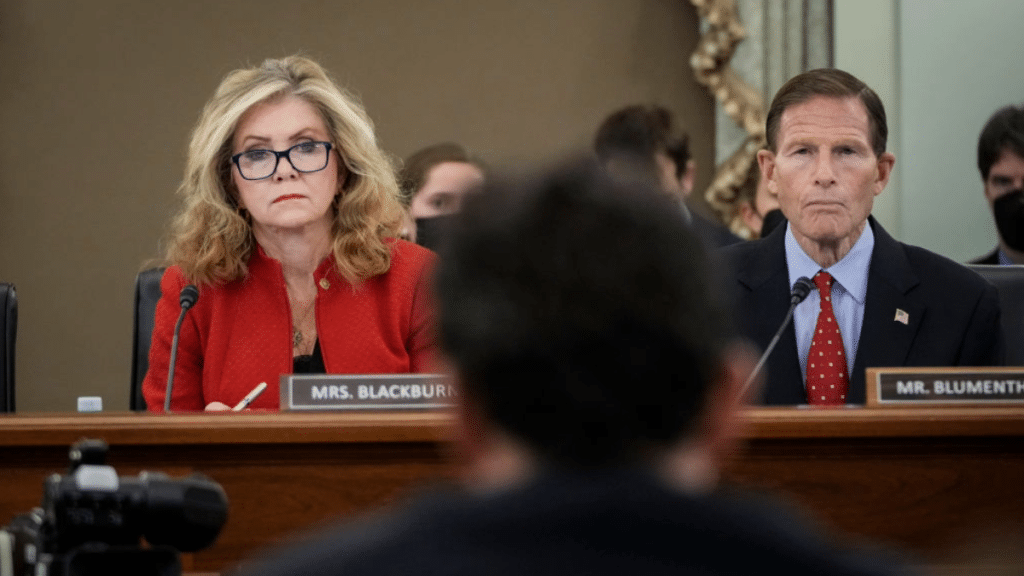

The Heritage Foundation explicitly argued for the bill to be used to block content about transgender people in a tweet earlier this year. KOSA co-sponsor Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) supported KOSA during a Family Policy Alliance event, following those comments by adding that “protecting minor children from the transgender in this culture’ should be among the top priorities of conservative lawmakers.” Her legislative director subsequently pushed back on the implication the comments were intertwined, saying KOSA would not censor transgender content online.

Democratic Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) also pushed back on the claims in NBC reporting, saying changes had been made to protect free speech. “Striking the right balance between supporting safe online spaces and protecting against toxic content targeting LGBTQ youth is very important to us, which is why my staff and I had extensive and collaborative conversations with stakeholders, including LGBTQ groups, to further clarify the legislative text so that it better reflects the intent of the bill,” Sen. Blumenthal said.

There is no technological silver bullet to solve this complicated challenge, and what might be harmful to one user can provide benefits for others, such as with personal stories about mental health or eating disorders. There are also constitutional and other legal protections for user-generated content and for platforms to have editorial control over moderation and recommendation systems.

Despite these intertwined challenges with content, a duty of care can in fact provide many important remedies. More direct control in the hands of children and parents can help provide individual control to train recommendation systems on appropriate and beneficial content that benefits the wellbeing of a user. Design measures are also important for addressing a rise in sextortion with controls over who can contact a child and preventative measures to identify potential sexual exploitation or abuse online.

What good is a duty of care if it does not hold up to constitutional scrutiny under the First Amendment? This is important to get right, and there are new efforts to find consensus in recent months.

Next Steps for a Duty of Care

Public pressure helps prioritize the efforts of those working inside technology companies to improve safety design measures and provide resources to improve the wellbeing of users. Ultimately, this advocacy combined with legislative and regulatory action should drive change, including solutions that many are already working on inside tech companies. Google and Meta have stated their dedication to developing age-appropriate design measures for users. The legislative push should include engagement with those companies to find consensus on those measures.

Last month, Google and YouTube released a legislative framework for youth online safety. The principles are promising and include an age-appropriate approach based on youth developmental stages, risk-based age assurance measures, balancing parental control options with autonomy for teens, safety by design measures, and a ban on personalized advertising for children and teens.

The University of Southern California Neely Center also announced an important effort in October, releasing a “Design Code for Social Media,” outlining expert consensus on nine actionable “design changes that would improve social media’s impact on society.

Age Verification and Privacy

Contrary to some claims, KOSA does not ban kids from joining social media or require age verification. Most of the bill would only apply to users known to be under 17, but there is no age verification process required in the legislation and social media companies already have to comply with an “objective knowledge” standard to protect the privacy of children under age 13.

In addition to the change in legal wording, KOSA explicitly has a section that states the bill does not require any additional data collection to determine the age of users or implementation of age verification or age gating measures.

However, one could reasonably argue that the bill’s requirement for a parent to provide “affirmative acknowledgement” before a child under 13 can create a social media account or use an online multiplayer game could effectively prevent a child from joining social media.

KOSA would also task the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to conduct a study on age verification, and would set specific requirements for the accounts of children under 17.

This debate is not so much about what is in the bill, but about concerns with a future internet where identification and age gating measures are required to participate in online spaces and engage in free and open conversation.

However, the debate is often constrained by the assumption that users would have to hand over a form of government ID, particularly a driver’s license in the US context. This is an important concern, but there are verification options available to authenticate a user without exposing their identity or personal information. University of North Carolina researchers Matt Perault and Scott Brennen published a comprehensive report about privacy tradeoffs for age verification measures in policy offering suggestions for regulators and policymakers.

Device level techniques offer a path forward for age assurance and parental controls, along with programs like the European Union’s personal digital wallet initiative, which does not expose the identity of a user in the authentication process.

The USC Neely Center’s consensus design code recommends that the best, privacy-protecting method of age verification is at the device level, providing technical indicators if the owner is under a certain age without identifying the user. University of Michigan professor Jenny Radesky, a leading researcher on children’s device usage, has long advocated this approach with a focus on quality of time spent over limiting children’s access to devices.

It is unclear how parental agreement and access to parental controls would work, but the legislation seems to draw from current measures required under the Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule (COPPA) for children under 13 to “obtain verifiable consent” from an adult. Many parents already use these tools with research findings by Microsoft earlier this year finding that 81% of parents report already using at least one safety tool for their children.

This is again an area for nuanced debate for safety controls, but where concerns appear to be tied to the future of the internet where parents have more control over their children’s devices and online experiences, especially for younger children.

What’s Next?

KOSA still faces many hurdles. Despite unanimous passage out of committee and nearly 50 co-sponsors in the Senate, significant revisions would likely be needed to get it passed — that will take time which Congress simply does not have this year.

Debate on KOSA is taking place amid a global regulatory movement for online safety rules. The United Kingdom’s Online Safety Act was signed into law earlier this year and the European Union’s Digital Services Act is now being enforced for the largest social media companies. The Global Online Safety Regulators Network launched in November 2022 with six member countries and four observers, spanning from Australia to South Africa and Ireland.

While there are a growing number of laws passed by state lawmakers across the US, KOSA does not have a clear path forward with continued opposition in a political climate that requires near unanimous agreement to legislate.

In some ways, this feels like déjà vu. Legal hiccups with online safety regulation date back at least to the Communications Decency Act of 1996. The law was almost entirely struck down due to constitutional free expression issues. Only Section 230 remains, which has become a key pillar for internet law and policy.

This year, KOSA passed out of committee on the same date in July as it did last year. It's worth recalling that KOSA came out of a series of Senate hearings, including one with Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen. Now, there is a new Facebook whistleblower, Arturo Béjar, who testified at a Senate hearing aimed at giving new wind to the bill last Tuesday. KOSA’s supporters hope his testimony gives the bill a final push to secure more than 50 co-sponsors in the Senate.

Béjar, a former Facebook safety engineering director, testified that Instagram has concrete research on harms to children and teens, but repeatedly fails to take action.

In Wall Street Journal reporting last week, Béjar described how his daughter stopped reporting sexual harassment and inappropriate comments to Instagram because the company rarely responded or took action. In fact, the Wall Street Journal investigation found that Meta added steps to the reporting process, making it more difficult to submit a report. The company claims that new steps were added to reduce frivolous reporting. If passed, KOSA would require companies to respond to harmful interactions that children experience on platforms within one to three weeks.

While Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) has said children’s online safety and privacy legislation are his top priorities, Senate floor time is extremely limited with a backlog of spending bills and nominations and urgent geopolitical crises.

And, KOSA lacks companion legislation in the House Energy and Commerce Committee, where members have prioritized comprehensive federal privacy legislation to address children’s online safety issues. Even that priority legislation has yet to be reintroduced in the current Congress.

These political obstacles mean the most likely path to passage is still through the annual federal spending bill this year, where a single powerful senator or congressional bloc can strip out so-called “rider” legislation.

While there is now an end-of-year push, the legislation may have a better chance of moving in the lame duck session following the presidential election next year. However, a single senator could still hold up the process of bringing the bill to the Senate floor at any point, and the same challenges remain with tucking KOSA inside must-pass legislation.

That’s not to say that political obstacles will prevent anything from being done in D.C. to protect the abuse of children online. We remain optimistic thatthe efforts of parents and advocates will not go to waste.

For instance, the Biden administration is currently working on “voluntary guidance, policy recommendations, and a toolkit on safety-, health- and privacy-by-design for industry developing digital products and services.” These measures are expected to be released by an interagency Task Force on Kids Online Health & Safety in spring 2024.

The FTC also has important authority. Commissioners are planning to hire child psychologists by fall 2024, and an FTC complaint brought by the children’s safety advocacy group Fairplay could spark the investigation of a service that enables the anonymous harassment of teens and falsely promises clues about who is bullying them for a fee.

State attorneys general and school districts are also taking legal action against social media companies, alleging privacy abuses and deceptive design that harms children.

Recommendations

KOSA marks an important beginning for safety by design policy that attempts to give users more control over their online experiences and requires companies to take proactive safety measures, conduct internal tests, and provide more transparency about those efforts and how their design works.

To move forward, it is necessary to more narrowly define the problems the bill is trying to address. Congress should focus on the core, less-discussed parts of the legislation. In particular, efforts to address child sexual exploitation and abuse and to encourage design that gives users more control of their experiences with online messaging and algorithmically powered content feeds should be emphasized. These are uncontroversial measures that can save lives. They are achievable and are already being implemented in policy around the world.

While the Kids Online Safety Act does not yet hit the mark, it should not be dismissed out of hand. Policymakers, advocates, academics and industry must work together in good faith to pass legislation that protects against the worst harms children face online, and to establish a legally protective duty of care to empower children and parents to take back control of their online experiences.

This piece has been updated to clarify which provisions of KOSA apply to children and which to teens.

Authors