Researchers Embrace Complexity in Social Media and Teen Mental Health

Tim Bernard / Feb 20, 2026

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg leaves after testifying in a landmark trial over whether social media platforms deliberately addict and harm children, Wednesday, Feb. 18, 2026, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes)

On Wednesday, Mark Zuckerberg testified in a California court in a case that argues that a set of major social media platforms harm users through addictive design features; earlier this month, the EU announced preliminary findings that TikTok’s addictive design is in breach of the Digital Services Act. While many have decided that these platforms are broadly harmful, at least in excess and especially to young people, we still have many gaps in our knowledge about the impact of social media overuse.

At the heart of the intense academic, social, and policy debates over teen access to social media, is the question of how to best study social media harms to adolescents’ mental health. A research project by Amber van der Wal, Ine Beyens, Loes H. C. Janssen, and Patti M. Valkenburg, published last December in Current Psychology as “Diverse platforms, diverse effects: Evidence from a 100-day study on social media and adolescent mental health,” included some methodological innovations that shed light on this question.

The team recruited 479 14-18 year olds in the Netherlands and gave them an initial survey to gather demographic, social media habits and psychological baseline information. They then administered financially-incentivized daily questionnaires regarding each subject’s use of social media platforms that day and three specific dimensions of their psychology. These were: well-being, self-esteem, and friendship closeness—selected for their salience for mental health in this age group.

Two research questions steered the study. The first was to assess the prevalence of “within-person unity” and disunity, that is, whether, for each individual, increased social media usage is correlated with the same direction of change across psychological dimensions or different directions of change.

| Unity | Other | Disunity | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Outcomes

with increased social media usage |

3 null | 2 null & 1 positive | 2 positive & 1 negative |

| 3 positive | 2 null & 1 negative | 2 negative & 1 positive | |

| 3 negative | 1 positive, 1 negative & 1 null | ||

| 2 positive & 1 null | |||

| 2 negative & 1 null |

The second research question interrogated potential risk and protection factors for social media harms using three measures: age, gender, and “self-concept clarity,” i.e., “how clearly and confidently an individual’s self-concept is defined, and how consistent and stable it is over time.”

Key findings

The topline result for the first research question is that, with increased use of social media, most—around 68%—of the subjects displayed unity outcomes and for almost 60% of subjects these were negative (i.e. two or more negative and no positive outcomes). However 13.6% experienced disunity, i.e., a combination of positive and negative outcomes, with increased social media usage. Broadly speaking, this suggests an association between increased social media use and generally negative psychological outcomes for most adolescents but a mix of positive and negative outcomes for a significant minority.

The risk factor analysis did not reveal any statistically reliable effects, which may have in part resulted from fairly small sample sizes and imbalances in the subject group. (There were suggestions of trends such as more girls and low self-concept clarity subjects in the unity-negative group, but these should be interpreted cautiously.)

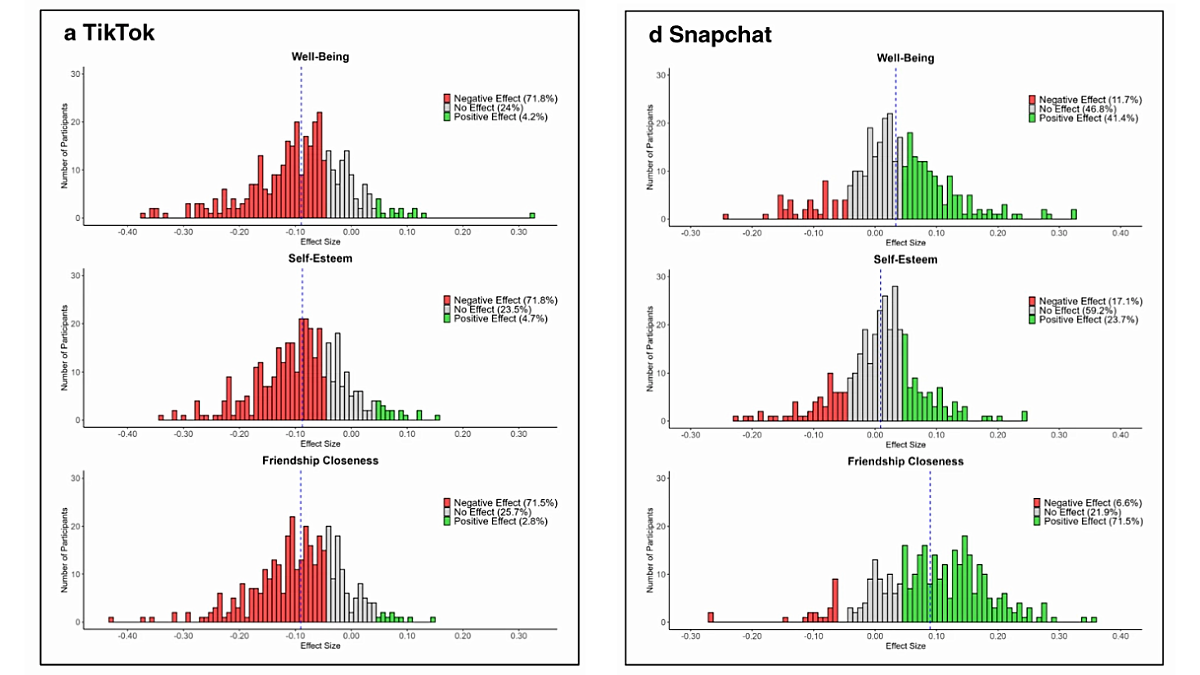

The third, and perhaps most striking, finding was the variance in psychological outcome depending on which specific social media platform was being used more. Data regarding the top five social media platforms in the study (TikTok, Snapchat, WhatsApp, Instagram, and YouTube) was analyzed and the use of TikTok, YouTube, and, to a slightly lesser extent, Instagram was generally associated with negative outcomes. However, WhatsApp and Snapchat were more typically associated with null and positive outcomes.

The authors discuss possible reasons for this variance: the former platforms are loci of idealized imagery; they have recommendation algorithms that can repeatedly surface problematic content; and they rely on engagement-optimization features that take away time from potentially more enriching activities. In contrast, the latter platforms are tools for interacting with friends—Snapchat’s apparent advantages over WhatsApp with respect to well-being, it is speculated, may result from ephemeral messaging “limiting exposure to risks such as upward social comparison, algorithmic content overload, or displacement of social interactions.” The fact that Instagram has a lower bar to posting and combines content discovery with friend-group interactions fits well with this line of reasoning, as it fared slightly better than TikTok and YouTube in the study.

The platforms with the most negative and most positive outcomes in the study, taken from Fig. 2, “Distribution of person-specific effects of the top five social media platforms on mental health.”

Not a causal study

The paper’s footnote clarifies, “[t]his is a descriptive study, thereby limiting our ability to draw conclusions about cause and effect.” Its regular use of the terms “effect,” “impact,” and “outcome” should therefore be interpreted in this light. It is not hard to imagine that, for instance, the relationship between negative senses of well-being, self-esteem, and social connection on the one side and extended scrolling on TikTok or watching hours of YouTube on the other may not have an obvious direction of causality. Conversely, on days when teens felt closer to their friends, they spent more time conversing with them on SnapChat or WhatsApp. Some of the authors’ summary statements suggest that they too had trouble keeping this distinction in mind when they write, for example, that “[t]hese findings indicate that social media use is a contributor to mental health problems in the majority of adolescents.”

The preliminary nature of the study

The authors of the study suggest that this is only the beginning of a new strand of research, recommending a plethora of new directions that their study opens up. The presence of significant groups experiencing different varieties of unity and disunity suggests the need for further investigation of what risk factors correspond with these different outcome patterns in order to move towards personalized recommendations.

A range of other dimensions of mental health could also be studied, and researchers can attempt to zero in on the specific platform features that seems to be associated with positive and negative outcomes. Adjusting the timing of the daily questionnaires may also elucidate how adolescents’ mental states change across the day in relation to their social media usage. Different demographics could be studied and screen time measures could be assessed more reliably.

Reframing the debate with granularity

What most stands out from this study, in contrast with so much of the public debate, is the multiple dimensions of granularity with which the researchers engaged. Firstly, they deliberately chose a timeframe to examine that stood at middle ground between short-term studies of a couple of weeks and longer-term studies that measured correlations over years, recognising that some relationships may not be captured by either of these approaches. Next, they focused on different dimensions of mental health, positing (and demonstrating) that at least some subjects would experience disunified outcomes. They also attempted to examine how social media and mental health would interact differently for different segments of the population. Lastly, they identified dramatically varying patterns for different platforms and platform types.

When countries are debating and rolling out wholesale bans of social media for adolescents and developing somewhat rigid design codes, it is refreshing to see that some academics are favoring an approach that recognizes variety in the world of social media, complexity of mental health, and variation in the experiences of different segments of the adolescent population. (It is worth noting that the Australian social media ban includes Snapchat, a platform found in this study to be much more associated with positive and neutral mental health outcomes than negative ones.) As indicated above, for many of these factors, these authors also encouraged further research to examine even more avenues of difference in service of providing truly individualized guidance for young people’s safe use of social media.

This approach could go a long way to elevating public understanding of the impact of social media use on adolescents... eventually. The authors note that even platform-specific data can be of limited application as platforms change over time—with Instagram’s shift towards algorithmic “content discovery” as the prime example. On this point, it is worth observing that it took at least 2.5 years from this study’s data collection in the first half of 2023 to final publication in December 2025. Considering how quickly platforms can evolve when there is a dedicated internal effort, the slowness of scientific progress constitutes a significant limitation on its ability to help us understand their impact on individuals and on society.

The researchers suggest that policymakers should focus on design elements with an eye on psychological needs, “discouraging agency-reducing features like autoplay and infinite scroll,” rather than implementing broader rules on screen time or on social media regardless of platform. Beyond this, politicians and regulators would be wise to follow the authors’ lead and embrace the complexity of the relationship between adolescent social media use and mental health by paying attention to regulations’ impact on minorities, divergent psychological effects, and the constant flux in platform features and how they are used.

Authors