Scrutiny Over Google’s Ad Business Should Expand to the Entire Ad Tech Market

Karina Montoya / Jun 21, 2023Karina Montoya is a journalist with a background in business, finance, and technology reporting for U.S. and South American media. She researches and reports on broad media competition issues and data privacy at the Center for Journalism & Liberty, a program of the Open Markets Institute, in Washington, D.C.

The European Commission last week charged Google with violating antitrust laws by abusing its dominance in the market for advertising technologies, called “ad tech”. The Commission acknowledged Google’s misconduct may be so profound that a mandatory divestment by Google of parts of its ad tech services would be the most effective solution to repair the damage it has caused.

With this, Europe’s top antitrust regulator joins the U.S. Department of Justice in seeking to dismantle Google’s monopoly power over the market where advertisers and publishers meet to buy and sell ads. But the implications of these antitrust cases should go beyond Google itself. The allegations by the DOJ and the European Commission should help to shine a light on how problematic the ad tech market has become, as it has progressively consolidated under Google’s influence over the last 15 years, per the DOJ lawsuit.

Ideally, the scrutiny that antitrust enforcers are placing on Google’s business model in the ad tech sector should prompt all market players, including web publishers and advertisers alike, to rethink how this market should be organized. Without change, ad tech will continue to disproportionately benefit Big Tech middlemen, while hurting news publishers and undermining personal privacy.

Understanding the Conflicts of Interest

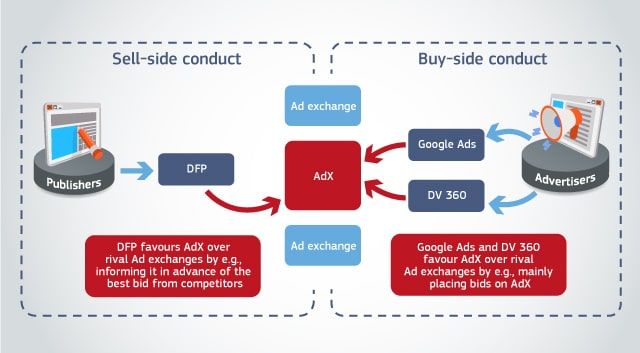

Let’s recall that publishers and advertisers use three main ad tech products to place ads on the open web: publisher ad servers (for publishers to manage their ad spaces), ad-buying tools (for advertisers to buy ads), and ad exchanges (where supply and demand meet). For each webpage we load, publisher ad servers auction available ad space, and ad-buying tools respond with bids. The ad exchanges basically compete by the volume of bids they clear for each side of the market.

Ad tech platforms operate on both sides of the market even though they represent two distinct types of interests. Publishers want to get the maximum value for the advertising placed adjacent to their content, hence charging more for ad space, while brands want more effective ads at the lowest possible price. European and U.S. regulators regard this as a problem and argue that this structure gives Google the ability to favor its own ad tech tools to the detriment of other competing providers, publishers, and advertisers.

Big Tech corporations in ad tech create another key conflict: they intermediate ad sales between publishers and advertisers, and they also act as publishers by selling ads on their own websites and apps. Although the current complaints against Google’ ad business focus on attempts to monopolize and abuse of monopoly power in ad tech, their preliminary evidence opens the door to question whether other Big Tech players in this market, operating just as Google does, may be following the same tactics to favor their own ad tech tools or other adjacent businesses they operate.

Meta, similar to Google, runs ads on its own social networks, Facebook and Instagram. It also has the ad-buying tool Facebook Ad Manager. Up until 2020, Meta used to represent web publishers with its Facebook Audience Network, which now focuses on mobile apps. Microsoft also operates in all sides of the ad tech market with Xandr, which is the second-largest exchange after Google’s, according to an antitrust lawsuit by the Texas Attorney General. At the same time, Microsoft sells ads on LinkedIn, the free version of Outlook, and its MSN portal. Potentially, it may even start placing ads on Xbox videogames that users pay a subscription for – something fans aren’t excited about.

Endless Exploitation of Personal Data

Another big problem in the ad tech market, which isn’t part of the antitrust cases, is that of data privacy. Google and Facebook, which since 2016 garner about half of the U.S. digital advertising spend, have enabled an ad auction system based on almost unrestricted user surveillance to fuel their ad tech algorithms. As a result, Big Tech advertising platforms are unable to control how many companies present in the ad auctions access such data, and where exactly their algorithms are placing ads.

This is what Johnny Ryan, senior fellow at the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL), calls the “world’s largest data breach.” A report by the ICCL shows that the location of a typical internet user in the U.S. is revealed to an inordinate number of companies more than 700 times a day, much greater than the European rate of 376. This lack of privacy and transparency goes a long way toward explaining the headlines about Google’s ad business funding disinformation sites across the world, as ProPublicaand Check My Ads Institute have reported. Currently, the ad auction system that fuels much of the current ad tech business worldwide is under litigation in Europe.

Competition, But of What Kind?

Google seeks to portray the ad tech market as “very competitive” because the tech behemoth is just one “one of hundreds of companies” in this sector. But the sheer number of players does not equate to an absence of market concentration. In the market for ad buying tools, in terms of revenue, the top four players make up 90% of the market, with the top two accounting for most of it. The top four players are Google, Amazon, Trade Desk, and Yahoo, according to the firm Advertiser Perceptions. On the side of publisher ad servers, Google captures 90% of the market, according to the DOJ.

For sure, there are more tech behemoths growing in digital advertising. Amazon is one of them. But Amazon poses both the same and new problems as well. I recently wrote about the business model behind Amazon’s growth in advertising, known as “retail media.” Under this model, Amazon acts as a publisher by selling ads on its digital properties, and operates in all sides of the ad tech supply chain for other web publishers as well, “enriching” such ads with Amazon’s unique shopper data. Whether the data is obtained from the shoppers directly or not, when tech giants operate in multiple markets and on all sides of ad tech transactions, the conflicts of interest remain the same.

News publishers have flagged these conflicts for years. In the U.S. alone, last year more than 200 local newspapers filed antitrust lawsuits against Google and Facebook for the same issues for which regulators across the globe are now suing Google. The European Commission and the DOJ face an uphill battle against Google, and we are unlikely to see a resolution of these cases for at least a few years. But just reading the cases as they are today, it is clearly time to reconsider the broader function and organization of the ad tech industry, and to address the market consolidation and invasion of privacy on which it is premised.

Authors