Synthetic Media Policy: Provenance and Authentication — Expert Insights and Questions

Ellen P. Goodman, Kaylee Williams, Justin Hendrix / May 2, 2025AI-generated or altered text, imagery, video, and audio—collectively referred to as “synthetic media”—now permeate the internet and have already begun transforming industries ranging from entertainment and advertising to journalism and education.

The rising prevalence of synthetic media has sparked intense debates over their potential to erode “reality,” undermine intellectual property rights, threaten the privacy and safety of private citizens, spread disinformation, enable scams and fraud, and sow discord on a global scale.

On December 13, 2024, just weeks after the US Presidential Election, a diverse group of experts—including computer scientists, First Amendment and information law scholars, government officials, and cybersecurity specialists—gathered for a ‘Roundtable on Synthetic Media Policy’ in Washington DC to discuss these threats and establish a shared research agenda for the coming year. Hosted by Rutgers Law School’s Institute for Information Policy and Law in partnership with Tech Policy Press, the event focused on open research questions and potential solutions—technical, regulatory, social, and structural—to the many challenges associated with synthetic media.

Participants reached consensus on a handful of shared priorities—such as the importance of harm reduction, increasing media literacy, and preserving free expression online—and, as importantly, identified areas of disagreement about matters such as provenance standards, tradeoffs between privacy and transparency, and the role of digital forensics in battling harmful digital clones and fakes.

The following outlines some of the findings of the convening, which do not reflect the precise views of every participant.

Question #1: What are the limits of synthetic media detection, and who are the intended consumers of detection-based products?

For years, research labs, intelligence agencies, and private companies have been designing forensic tools, protocols, and systems intended to help people determine whether a given piece of content (such as an image or a video) was likely generated or altered by AI. While these forensic detection technologies have grown more sophisticated over time, several experts agreed that even the most advanced synthetic media detection techniques are extremely time-consuming and resource-intensive, making them difficult to deploy at scale. Furthermore, there are only a small number (roughly “half a dozen,” according to one expert) of companies and research firms performing advanced work on forensics in the United States, a handful in Italy, and fewer in other democratic countries. This suggests that the resources required to scale robust AI detection as a way to combat social media harms—including fraud, disinformation, and non-consensual intimate imagery—are lacking, to say the least, particularly outside of the Global North.

Even when an expert forensics team applies its tools to a piece of potentially synthetic media, detection technologies do not yield clear, unequivocal results. Significantly, the best of these methods can only calculate a likelihood that a given image has been generated by AI or digitally altered from its original form. They cannot make a definitive determination that content is “synthetic” or “authentic,” as there is too much variation to achieve high-confidence, definitive results, even by the best detectors.

More importantly, even if there are definitive forensic determinations, there may be a misalignment with the public’s understanding of what it means for a piece of content to be “digitally altered” or “manipulated.” Not all manipulations are created equal. For example, most people would not consider an image “digitally altered” if it were simply cropped or color-corrected in Photoshop. People may be divided on other modifications, such as “touching up” subject faces and adding artistic filters. There is probably more consensus around the removal or addition of elements. The rising ubiquity and broad accessibility of AI-powered photo editing software, much of which is now built directly into smartphone cameras, is also changing public perception of what constitutes an “authentic” image, making the reliable identification of synthetic media that changes the meaning of that content much more difficult. To denote content as “altered” is a sociotechnical exercise that would ideally be tuned to evolving communications dynamics.

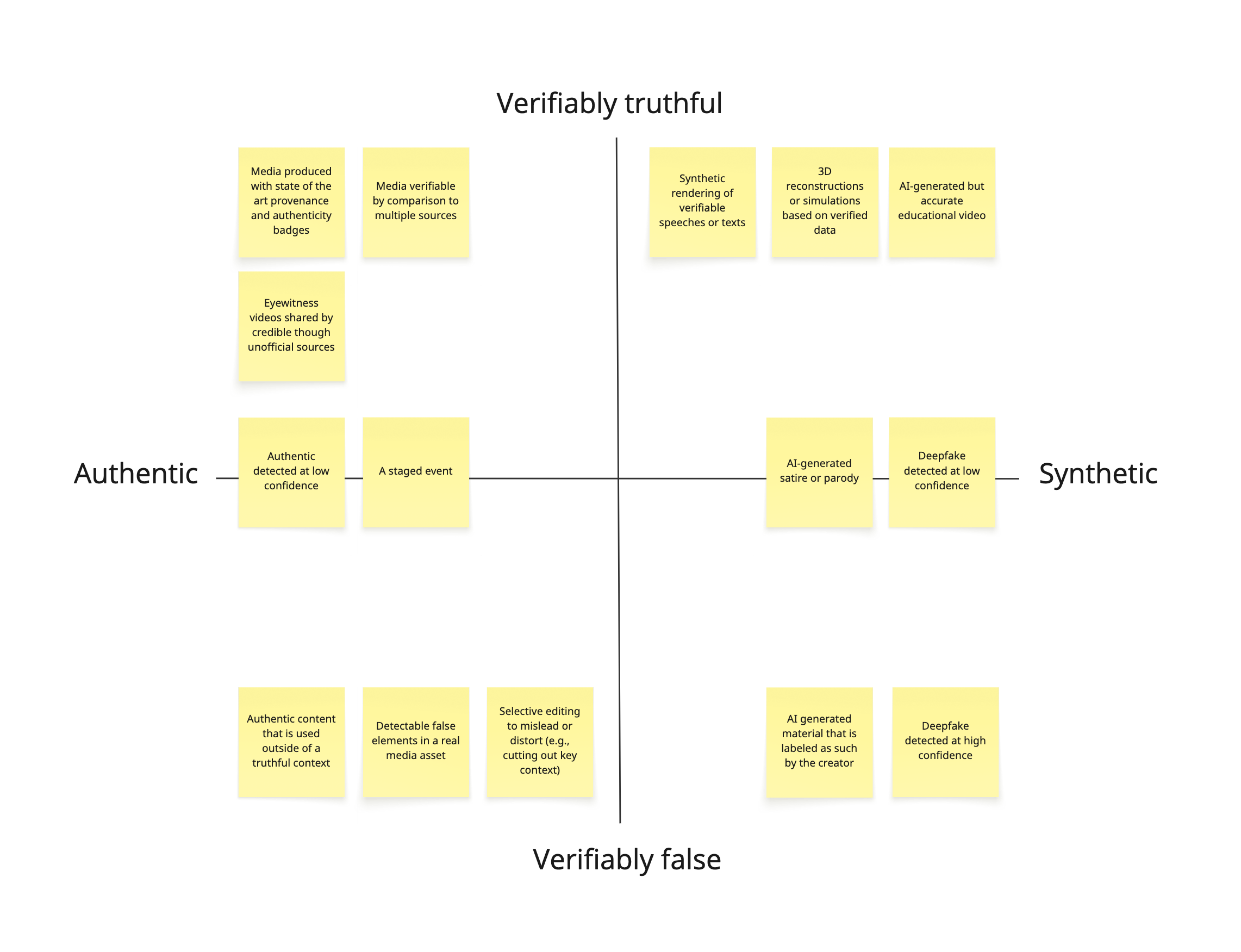

Ultimately, digital alteration does not necessarily cause deception. The gap between the technical term “manipulation” and the social/legal term “deception” is potentially problematic for assessing and addressing synthetic media harms. For example, labeling content as synthetic or manipulated may imply that it is deceptive or otherwise harmful when that may not be the case. Synthetic parodies and art illustrate the point. An obvious parody or imaginative work containing synthetic elements would technically constitute manipulated media, while rarely deceiving. By the same token, identifying content as authentic or minimally altered may imply that it is trustworthy when that may not be the case. For example, an infographic generated using an LLM might accurately display verifiable data, while a cleverly cropped but otherwise unaltered photograph might give viewers a distorted understanding of a real-world event. Labels that cleave content into synthetic/authentic or manipulated/unaltered binaries may not only create confusion for online consumers, but also for those around the world making high-stakes legal decisions based on visual evidence.

Illustration: A matrix categorizing media content by its authenticity (Authentic vs. Synthetic) and veracity (Verifiably True vs. Verifiably False), with examples.

Despite these limitations, synthetic media detection remains a critical area of research for a variety of stakeholders, including the national security community, human rights defenders, lawyers, and journalists. While the technology may never be able to satisfy the public’s desire for a quick and easy way to verify whether an image is “authentic,” it will likely still play a crucial role in advancing trustworthy information, especially as the challenges that AI poses become more significant. To continue this work, digital forensics professionals and others in this space will need to prioritize certain use cases and stakeholders over others and develop tools tailored to those domains.

Question #2: How useful is content labeling and provenance disclosure?

Content provenance and watermarking are methods used to encode media with metadata indicating the source of origin and any alterations. Such metadata can be displayed to end users in the form of a provenance legend or content label. These methods are not foolproof; technically savvy actors can exploit metadata and watermarking techniques to make an authentic image look synthetic, or vice versa.

Workshop participants considered the utility of labeling and provenance disclosures in light of the literature on content labeling in general. In the years since 2016, when Facebook first started putting “content warnings” next to verifiably false claims on the News Feed, dozens of academic studies have sought to measure the efficacy of fact-checking labels designed to alert readers to the presence of disputed or inaccurate information within a given post. The results of these studies vary widely depending on the design of the labels, users’ pre-existing beliefs about the subject matter, and other factors. But the research tends to suggest that labels have only a modest effect on the spread of disinformation and can create a variety of potential backfire effects, including seeding the misconception that unlabeled assertions are accurate—a phenomenon known as the “implied truth effect.”

There have been fewer studies on the effects of labeling media as synthetic, manipulated, or otherwise generated by AI in whole or in part. Even so, many social media platforms are requiring synthetic media labels, particularly on content that could be perceived as meaningfully deceptive. For example, Meta has mandated that users across its platforms label “photorealistic video or realistic-sounding audio that was digitally created, modified or altered, including with AI.” It does not, however, require a label for all synthetic media. This means that, for example, a “video of an outdoor landscape, created in a style resembling a cartoon” would not need to be labeled under Meta’s current policy. The distinction between the included and excluded content seems to track the distinction between deceptive and non-deceptive content, except that lots of “modified or altered” realistic-seeming content may not be deceptive. Strict compliance with the mandate (unlikely) could result in over-labeling and attendant loss of meaning.

Meanwhile, some state legislatures in the US have adopted similar requirements for synthetic media related to elections, with varying definitions of what constitutes “synthetic.” Arizona, for example, now requires “clear and conspicuous” disclosures to appear alongside any “image, audio recording or video recording of an individual's appearance, speech or conduct that has been created or intentionally manipulated with the use of digital technology” within 90 days of an election. Indiana has established a civil right of action for political candidates who are deceptively depicted in “fabricated media," defined as “an audio or visual recording of an individual's speech, appearance, or conduct that has been altered without the individual's consent such that: (a) the media conveys a materially inaccurate depiction of the individual's speech, appearance, or conduct as recorded in the unaltered recording; and (b) a reasonable person would be unable to recognize that the recording has been altered.” These disparate legal definitions further demonstrate the challenges associated with synthetic media detection described above; namely that “digitally manipulated” content is not always deceptive, and vice versa.

At least one of these laws (California’s AB 2655) has been overturned in federal court as a violation of the First Amendment by compelling speech in a way that is not sufficiently well tailored to the government's interest in preventing deception. Significantly, the court expressed concerns that labels on parodies or other synthetic media that is not deceptive unduly burdened speakers and stigmatized their expression. The issue is not only that the “squeeze” of the labeling isn’t worth the “juice” of transparency with the public, but that the juice itself could sour if people come to conflate AI manipulation with deception. The contours of the First Amendment considerations are still very much uncertain when it comes to AI-related litigation, as are the implications of synthetic media labeling on consumer understanding.

Experts at the roundtable noted that clearly labeling synthetic media—to the extent that reliable provenance and detection methods even make that a reliable practice—is often perceived by politicians and others as an “all-encompassing solution” to the epistemic turmoil created by AI-generated images and video. This faith in labeling as the “solution” is misplaced, both because it is not easily operationalized and cannot address harms unrelated to consumer recognition of synthetic sources.

The prevailing theory underpinning the labeling strategy is that if average users can distinguish what is “real” from what is “AI-generated,” they will be less likely to be deceived and to share deceptive content. However, as one expert pointed out, this logic relies upon the fraught assumption that all content can be reliably sorted into mutually exclusive categories such as “human-made,” “AI-generated,” and that “synthetic” is more likely to correspond with “false” and “authentic” with “true.”

Several participants noted, drawing on communications literature, that trust is relational. People trust content based more on its source (original or intermediate) than on labels appended to it. In considering the utility of synthetic media labels or metadata, then, it might be better to focus on specialized consumers and contexts rather than on informing ordinary end users. For example, the identification of synthetic media, digital alterations, and provenance more generally is important for researchers, librarians, information specialists, model developers, agents, and fact-finders in many fields—even if an individual’s knowledge of these alterations in the ordinary flow of communications turns out to be less impactful.

Those whose work focuses on individual (as opposed to epistemic or societal) harms caused by synthetic media pointed out that content labels often fail to undo the damages inflicted by embarrassing, dehumanizing, and hateful synthetic images. One participant pointed out that sexually explicit deepfakes, for example, are often labeled as such by the creators and shared on websites dedicated explicitly to AI-generated content, which suggests that they are not, in fact, intended to fool anyone into thinking they are authentic depictions. These harms, along with those associated with other forms of nonconsensual synthetic depiction, such as AI-generated child sexual abuse material (CSAM), are not remedied via the use of content labels because the perceived “authenticity” of the content is beside the point of the content: to abuse the subject.

Areas where content provenance and labeling might be most useful and readily adopted are in enterprise domains where businesses depend on trusted communications and/or need to secure consumer trust. In such contexts, private actors have market incentives to be transparent about content origins and alterations. Workshop participants identified industry and business use cases where this might be the case, including insurance, financial services, and e-commerce areas. There remain questions about where the market will supply sufficient transparency and where it will not, and to what extent and how.

These insights suggest that while content labels and AI use disclosures—such as those enabled by provenance technologies—can play a valuable role in addressing the harms of digital clones, fakes, and other synthetic media, policymakers at both the platform and government levels should be cautious not to over-rely on them as standalone solutions.

Question #3: How do we address the social dynamics and norms underpinning the harms of synthetic media?

As the cases involving synthetic sexual abuse content demonstrate, many of the harms posed by synthetic media are not easily mitigated with informational or tech-based solutions alone. In fact, many of the most concerning threats are not new to the AI era. Instead, they represent the intensification of longstanding patterns of abuse and discrimination toward vulnerable groups for the purposes of maintaining existing social hierarchies.

For instance, the prevalence of nonconsensual sexual content reflects the systemic commodification of women’s bodies and the normalization of gender-based violence. Similarly, the weaponization of synthetic media for political disinformation and propaganda reflects prevailing social forces around racial inequality, othering “out” groups, stoking polarization, and amplifying conspiracy theories.

Addressing these harms requires a holistic approach that combines regulatory and technical solutions with broader efforts to challenge the social norms and power structures at play. This might include public awareness campaigns, education initiatives to foster digital literacy, and collaborations with civil society organizations to address the root causes behind various manifestations of online harm. Without tackling the underlying social dynamics, the experts gathered in DC agreed that interventions targeting synthetic media risk addressing the symptoms rather than the causes of those harms.

These issues are deeply entrenched in modern society and will not be entirely uprooted even with dramatic regulatory intervention targeting technology. The kinds of reforms necessary to address these systemic patterns need to be just that: systemic. As such, they will require buy-in (both political and financial) from various sectors and stakeholders, many of whom currently benefit from incentives and dynamics that exacerbate intractable problems, from racism and misogyny to economic exploitation (either directly or indirectly).

Question #4: What are the downstream risks of the “liar’s dividend”?

The “liar’s dividend”—as defined by legal scholars Bobby Chesney and Danielle Citron in 2019—refers to an information ecosystem that is so rife with false and otherwise deceptive information that actors can avoid accountability for wrongdoing by claiming that any documentation of misconduct is “fake news,” “misinformation,” “manipulated media” etc. Another way to put this is plausible deniability for any bit of content. In their 2019 paper, Chesney and Citron argue that pervasive, deceptive synthetic media contributes heavily to the liar’s dividend because its very existence undermines public trust in authentic content. In a world where any piece of media can plausibly be dismissed as fake, individuals and organizations can exploit widespread uncertainty about the facts to avoid accountability or obscure the truth. This dynamic has profound implications for journalism, the legal system, and democratic governance, as it challenges the fundamental ability to establish a shared reality.

As synthetic media become more sophisticated and accessible, the liar’s dividend may reach a tipping point where skepticism about media authenticity becomes the default. Anecdotal accounts argue that we are already there. This state of affairs could empower malicious actors to weaponize doubt, dismissing legitimate evidence of wrongdoing as fabricated. For instance, political leaders might evade accountability for harmful rhetoric or actions by claiming that leaked audio recordings or videos are AI-generated. One expert posited that the growing popularity of generative AI could result in a world of content manipulation so ubiquitous that there is an epistemic collapse.

The societal consequences of this potential collapse are far-reaching. If people cannot distinguish between truth and fabrication, public discourse will become increasingly polarized, with individuals retreating further into ideological silos where only content that aligns with their preexisting beliefs is accepted as legitimate. This environment may foster widespread cynicism, causing people to lose ever more confidence in institutions, in democracy, and in one another.

One expert noted that the role of synthetic media must be considered against the broader and systemic degradation of information fidelity. Systemic trust erosion is not necessarily tied to the authenticity of particular units of content. This expert argued that distrust in informational integrity poses a challenge to journalism and communications far beyond a liar’s intentional manipulation.

Addressing this systemic distrust requires proactive measures to restore faith in media and digital content. With respect to the narrow issue of synthetic media, this includes promoting the adoption of content authentication technologies, such as open technical standards like those popularized by the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) to verify the provenance of authentic content. While the participants acknowledged it would be a long road to a fully interoperable internet that allows such standards to thrive, industry and business use cases will likely be adopted first.

Equally important are efforts to improve media literacy aimed at equipping individuals with the cognitive tools to critically evaluate the veracity of digital content. However, technical and educational solutions alone are insufficient. Policymakers, platforms, and civil society organizations must work together to establish norms and regulations that discourage the strategic weaponization of “plausible deniability” to evade public accountability. Without such efforts, the liar’s dividend threatens to deepen societal divides and erode the foundations of trust essential for democratic systems to function.

Question #5: How do we move past the “authentic” vs. “synthetic” binary?

Many of the issues discussed at the event alluded to a broader, conceptual challenge that the experts agreed requires urgent societal attention: the need to reframe how we think about the provenance and authenticity of digital content in an AI world. This issue is fundamentally tied to media literacy and public education, particularly as AI-powered tools become more deeply integrated into content generation across information industries like journalism.

As noted above, content labeling risks creating the false binary that a piece of content is either wholly “authentic” or entirely “synthetic.” In reality, the roundtable experts agreed that much of the content we encounter online today exists on a spectrum of human and machine involvement. For example, a video might be largely authentic but edited with AI-enhanced filters, or a news article might be written by a journalist who used AI tools to clean or analyze data. These forms of hybrid media challenge traditional notions of authenticity and truth, complicating how we assess the trustworthiness of what we see, hear, and read.

Moving past this binary requires a more nuanced understanding of how digital content is produced and a shift in public attitudes toward AI’s role in media creation. Public education efforts should emphasize that authenticity is not solely about the method of creation or modification but also about the intent and transparency behind the content, including who shared it. Tools that trace the provenance of digital media, such as metadata tagging or blockchain-based verification, could play a critical role in fostering trust without reinforcing outdated mental models. But there are complications with these tools as well, including potential implications for privacy and free expression, and significant technical challenges.

Ultimately, building a society capable of navigating the complexities of synthetic media will require collaboration between technologists, educators, policymakers, and civil society actors. By shifting the focus from “authentic vs. synthetic” to questions of accountability and transparency, the tech policy community will be able to seed a more sophisticated framework for understanding and engaging with synthetic media in the coming years.

In addition to addressing these open questions, the roundtable participants worked together to brainstorm possible metrics to indicate progress on synthetic media-related issues. The following are some of the ideas floated:

- Tracking C2PA adoption as a proxy for understanding its effects and potential for broad interoperability across the information environment.

- Estimating the number of news stories in which manipulated or AI-generated media play a role, including phenomena such as criminal or civil actions brought in relation to the propagation of such content.

- Recording the number of scams or fraudulent activities reported to authorities that involved the use of synthetic media.

- Tracking global Investment in distributed media forensics capacity.

- Measuring the average time of platform takedown for nonconsensual synthetic pornography and other problematic forms of synthetic media.

- Assessing public perception of viral incidents involving synthetic media.

- Estimating the size of the customer base and understanding the markets for harmful synthetic depictions (including CSAM and NCII).

- Identifying ways of measuring the liar’s dividend and intervening to counter it.

- Further study on the effectiveness of content labeling, fact-checking, provenance verification, and similar efforts.

- Recording the number of lawsuits that attempt to hold platform companies accountable for harms caused by synthetic media.

- Recording the number of new regulations introduced by state and federal governments related to AI-generated content and their resilience to legal challenges.

Going forward, it will be crucial to find creative ways to address these challenges and advance bipartisan proposals for regulatory and self-regulatory frameworks that can alleviate some of the threats described above. The latter half of the decade will require policymakers—and the public—to move beyond “synthetic or authentic” binaries. What is needed are broad coalitions of technologists, civil society actors, researchers, and others to partner to develop systemic interventions that may not yet exist.

With thanks to the Knight Foundation for providing financial support for the Workshop.

Workshop Participants:

- Scott Babwah Brennen, Director, NYU Center on Technology Policy

- Bilva Chandra, Former Senior Policy Advisor & Synthetic Content Lead, US AI Safety Institute

- Peter Chapman, Associate Director, Knight-Georgetown Institute

- Renée DiResta, Associate Research Professor, McCourt School of Public Policy, Georgetown University

- Nadine Farid Johnson, Policy Director, Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University

- Mary Anne Franks, Eugene L. and Barbara A. Bernard Professor in Intellectual Property, Technology, and Civil Rights Law at George Washington Law School, and President and Legislative & Tech Policy Director of the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative

- Josh Goldstein, Research Fellow, Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET), Georgetown University

- Ellen P. Goodman, Professor at Rutgers Law School, Co-Director of the Rutgers Institute for Information Policy & Law (RIIPL)

- Sam Gregory, Executive Director, WITNESS

- Justin Hendrix, CEO and Editor, Tech Policy Press

- Mounir Ibrahim, Chief Communications Officer & Head of Public Affairs, Truepic

- Kate Kaye, Deputy Director, World Privacy Forum

- Claire Leibowicz, Head of AI and Media Integrity, Partnership on AI

- David Luebke, Vice President of Graphics Research, NVIDIA

- Siwei Lyu, SUNY Distinguished Professor, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

- Abhiram Reddy, AI Safety and Security Research Assistant, Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET), Georgetown University

- Aimee Rinehart, Senior Product Manager, AI Strategy, The Associated Press

- Matthew C. Stamm, Associate Professor, Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, Director, Multimedia and Information Security Laboratory, Drexel University

- Xiangnong (George) Wang, Staff Attorney, Knight First Amendment Institute

- Kaylee Williams, PhD Student, Columbia Journalism School and Research Associate, International Center for Journalists

Authors