The Case for Regulating App-Based Work

Kambria Dumesnil / Jan 12, 2026

The Path by Sophie Valeix & Digit — Better Images of AI / CC by 4.0

This work should be simple. Pick up food, deliver it, and earn a fair wage.

Instead, as an app-based food delivery driver, I rushed to meet shifting expectations, drove through questionable areas, and accepted deliveries that barely covered the gas, all in hopes of staying in the good graces of a machine. I was micro-managed by an algorithm with little transparency, all under the guise of flexibility.

Now, as a tech policy researcher, I decided to explore the impact of artificial intelligence on the gig economy in the United States. I wanted to confirm what the research already suggested: algorithms, not drivers or consumers, set the terms of courier work. In November 2024, I signed up to deliver food to see firsthand what decisions were being made, how they felt in practice, and how they shaped my behavior. For several months, I picked up periodic shifts, usually 4-6 hours on Saturdays and a couple of hours in the evenings during the week.

The lessons came fast. No single moment felt dramatic, but together they created a working environment dominated by invisible rules, one in which access to income was filtered through a black-box algorithm.

Invisible control, real-world consequences

Many consumers and policymakers don’t realize that every meal ordered on apps like DoorDash or Uber Eats is routed not just through restaurants and traffic, but through a system of software-driven decisions. These platforms determine who gets which jobs, how much they’re paid, and whether they’ll be allowed to log in tomorrow.

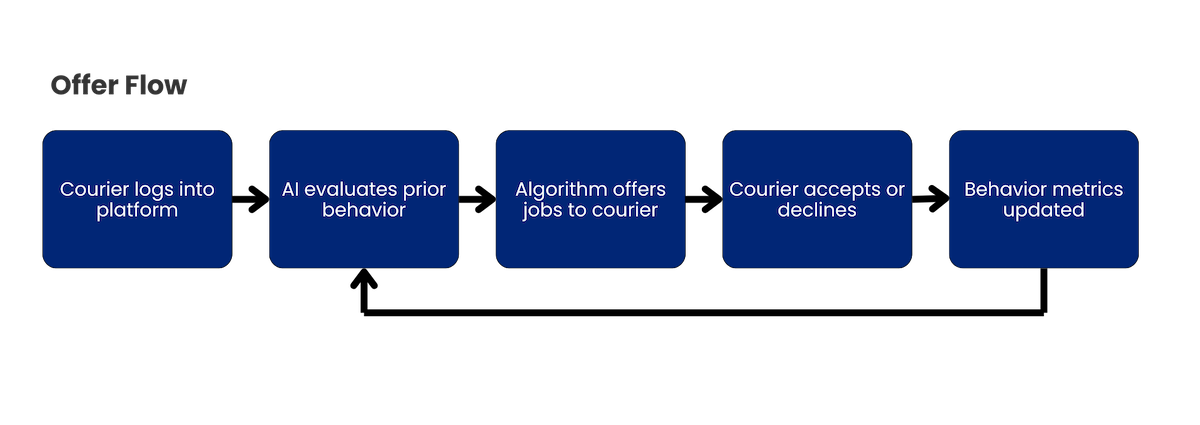

This practice, known as algorithmic management, replaces human supervision with automated rules that assign work, monitor performance, and impose discipline. In delivery work, this starts with order assignment, where drivers receive limited information and must accept or decline within seconds. If they decline too often, future opportunities may dry up, as platforms track this behavior and factor it into the driver’s acceptance rate.

How algorithmic management works in app-based delivery: a courier’s actions are constantly evaluated, shaping which jobs they see next.

For me, rejecting a low-paying offer often meant waiting 15 to 20 minutes for another one, gambling that a better offer might appear. Accepting too quickly, without checking the address, sometimes meant driving farther or entering areas I wouldn’t have chosen. One thing that was consistent throughout my experience is that I couldn’t see how decisions were made, and there was no person to ask.

Deactivation also loomed over everything. One late delivery, one poor rating, or one false flag from a user could result in being removed from the platform altogether. According to a 2025 Human Rights Watch survey, over a third of gig workers had been deactivated at least once and nearly half of those cases were later found to be mistakes.

The stress behind the steering wheel

Gig work is sold as flexible, but in reality, app-based delivery drivers often have less autonomy than traditional employees. Platforms dictate routes, provide customers with estimated delivery times, and penalize workers for delays, regardless of the reason. When I was stuck waiting at a train crossing or delayed by a slow restaurant, it was my rating and earnings that suffered. In some cases, a customer would take back their tip and I noticed that the offers I received slowed.

This tension between algorithmic rigidity and real-world variability creates constant psychological strain. Workers are asked to optimize around opaque systems, while the threat of being penalized for things beyond their control fosters hyper-vigilance and anxiety. Many push through unsafe conditions or illness just to avoid falling out of favor with the algorithm.

Research backs this up. Gig workers report elevated levels of stress and burnout and according to an article in The Journal of Urban Health, more than 20% have experienced physical injury or assault. Many drivers feel pressure to prioritize speed over safety, knowing that a late delivery, regardless of the cause, could mean lost income or deactivation.

State reforms aren’t keeping pace

Despite the growing reliance on gig labor, US labor law has largely failed to adapt. Most app-based couriers are classified as independent contractors and thus excluded from minimum wage laws, unemployment insurance, and workers’ compensation. Some states and local jurisdictions have taken steps to address this, but the results are mixed.

In California, Proposition 22 preserved contractor status for drivers but promised modest benefits such as a pay floor and a health care stipend. But the pay floor only applies to active delivery time, not waiting time, and enforcement has been virtually nonexistent. According to reporting from CalMatters, the state Industrial Relations Department has claimed they do not have jurisdiction because gig workers are not employees. Enforcement instead falls to the state attorney general, whose office has stated that it “do[es] not adjudicate individual claims but prosecute companies that systematically violate the law.”

Washington state took a different approach with House Bill 2076, offering enforceable protections like paid sick leave, workers’ compensation, and appeal rights — but only to ride-share drivers. Food delivery drivers were excluded entirely. So while some workers gained protections, others doing nearly identical work were left behind.

Both approaches share a fundamental flaw: They cement the contractor classification while leaving enforcement weak or fragmented. Neither guarantees gig workers the rights and protections that traditional employees take for granted.

Three steps policymakers can take now

To build a fairer system for app-based food delivery workers, policymakers must establish stronger baseline standards that account for how algorithmic systems actually shape work.

1. Guarantee pay for all on-app time

Many workers are only paid for “engaged (or active) time,” which is the minutes between accepting and completing an order. This ignores the hours spent waiting for offers, reducing effective pay and increasing precarity. States should set minimum earnings floors based on total logged-in time, not just delivery time, with expense reimbursement and tip integrity protections. While some platforms, such as Instacart, have independently begun ensuring tip protection from consumer “tip baiting,” it is a voluntary practice. Additional regulations like those implemented with California’s Proposition 22 are also needed to prevent tip subsidization, where the app lowers base pay for orders with higher tips.

2. Mandate transparency and fair process

Workers must know how dispatch, pay, and performance-scoring algorithms function, and have the right to contest decisions that affect their livelihoods. This includes the right to a timely, human-reviewed appeal for deactivation, as well as disclosure of shadowbanning or ranking practices.

3. Establish state oversight for algorithmic platforms

Even strong rules are meaningless without enforcement. States should create oversight units to license gig platforms, audit algorithmic practices, and ensure compliance. Funding should also support community-based Worker or Driver Resource Centers that help drivers understand and assert their rights. In Washington state, for example, the Department of Labor and Industries contracts with the Drivers Union to operate a Driver Resource Center for the tens of thousands of rideshare drivers statewide. A similar approach could benefit app-based food delivery drivers.

Toward fairness in an algorithmic-managed economy

When I began delivering, I assumed that following the rules would be enough. But the rules weren’t written down. They weren’t even consistent. Instead, they were hidden in algorithms designed to optimize outcomes for the platform, not for workers or even consumers.

The future of labor is already here; algorithms and machine learning are making real-time decisions about who gets paid, who gets punished, and who gets pushed out. Without updated laws and strong protections, the very technologies that promise efficiency will continue negatively impacting workers.

Authors