The Expanding Scope of “Sensitive Data” Across US State Privacy Laws

Keir Lamont, Jordan Francis / Mar 7, 2024

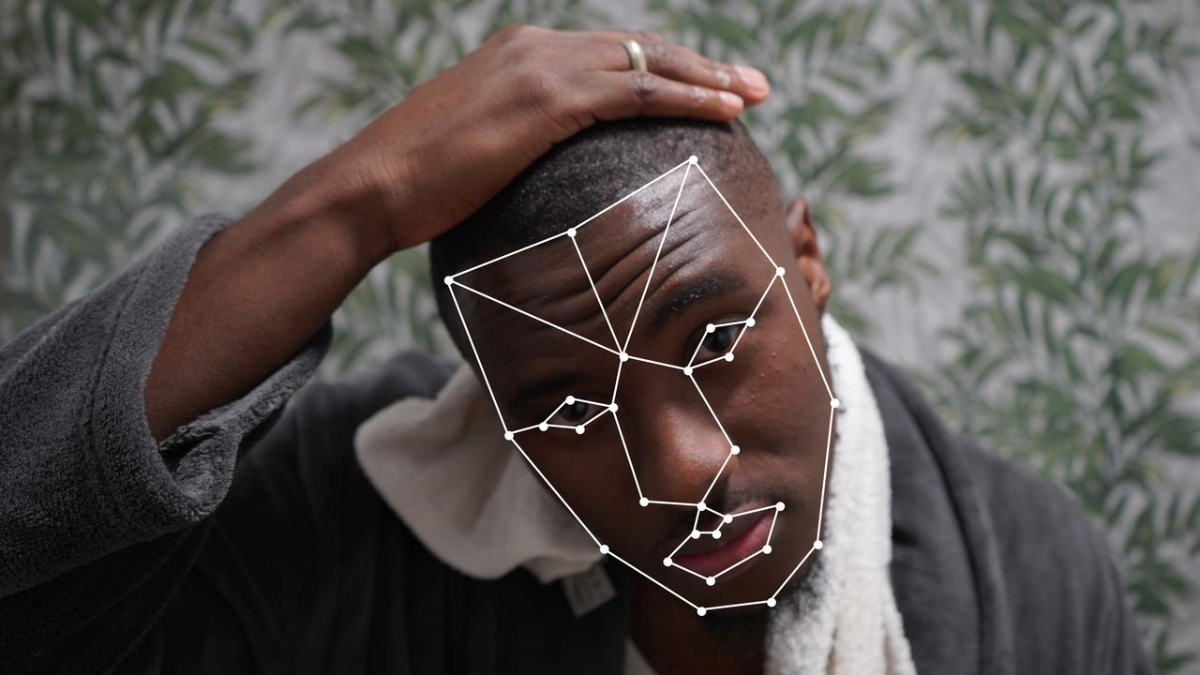

Image by Comuzi / © BBC / Better Images of AI / Mirror B / CC-BY 4.0

A paradigm shift is underway in US privacy law. In the absence of an overarching federal framework governing how businesses can collect, process, and transfer personal data, individual states are stepping into this void to establish baseline privacy rights and protections. Since 2018, fourteen states have passed ‘comprehensive’ privacy legislation designed to establish baseline protections for individuals’ personal data.

While there are numerous substantive differences across this slate of state privacy laws, one bedrock principle they share is the recognition that some categories of personal data pose heightened risks to individuals such that they should be subject to greater levels of protection. Typically, these laws recognize certain demographic information, information revealing health status, biometric and genetic data, precise geolocation data, and the information of known children as inherently sensitive.

However, there are some key differences between these laws. Most notably, recently enacted state privacy laws have expanded definitions of sensitive data in different directions—both by adding new categories of information and broadening the scope of the categories of data used in previous laws, such as biometrics and health information. The following resource represents an attempt to construct an ‘omnibus’ definition of sensitive data that describes how comprehensive state privacy laws use this term.

READ: An Omnibus Definition of “Sensitive Data” Across Comprehensive State Privacy Laws

Protections for Sensitive Data

In using this resource, it is important to remember that not only are there nuanced differences between how states define sensitive data, but the protections afforded to this class of information vary. For example, Utah and Iowa narrowly provide that individuals must be provided with notice and an opportunity to opt out of the processing of their sensitive data. California provides individuals a right to request that businesses “limit the use or disclosure” of sensitive personal data that is used to infer characteristics about them. The majority of states take a different approach by placing the onus on regulated businesses to obtain freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous consent in order to collect and process sensitive personal data. Many state laws also require that organizations complete a data protection impact assessment (DPIA) that weighs the benefits, risks, and mitigating safeguards used in their processing of sensitive data.

Notable Differences Amongst the Definitions of “Sensitive Personal Data”

In the short time since 2018, a flurry of newly enacted laws in 14 states have contributed to an expansion of the definition of “sensitive data” under US privacy law. The following states have had a particular influence on our ‘omnibus’ definition:

- California: When voters adopted the California Privacy Rights Act ballot initiative in 2020, California became the first US state with a comprehensive privacy law containing a concept of sensitive personal information. California’s definition stands apart from subsequently enacted laws by incorporating several elements that are more European-inspired than other US laws, such as information concerning union membership and philosophical beliefs.

- Texas: During the debate over the Texas Data Privacy and Security Act (HB4) enacted in June 2023, a local group opposed to statutory references to “sexual orientation” lobbied for this term to be removed as a category of sensitive data. Lawmakers responded by adding information relating to individual “sexuality” as sensitive data, arguably establishing broader protections than other states.

- Oregon: In July 2022, the Oregon Consumer Privacy Act (SB619) adopted a broader approach to the underlying definition of “personal data” than prior laws. While most laws have adopted a GDPR-inspired standard for defining personal data as information that is “linked or reasonably linkable” to an identified or identifiable consumer, Oregon went further by explicitly including “derived” data and stating that personal data can include an individual's connected device and also encompass information at the household level. Oregon also expanded the definition of “sensitive data” by adding categories such as “status as transgender or nonbinary” and “status as victim of a crime.”

- Delaware: Various states have designated data revealing an individual’s “mental or physical health condition or diagnosis” as a sensitive data category. In September 2023, the Delaware Personal Data Privacy Act (HB 154) became the first state law to explicitly include “pregnancy” as covered health information. Delaware also reworked its exclusion for publicly available information, only carving out information that individuals have made publicly available if included in “widely distributed media.”

- New Jersey: S332, enacted in January 2024, created expanded protections for health privacy by adding mental or physical health “treatment,” in addition to “condition or diagnosis,” to its definition of sensitive data.

Looking Ahead

This year, multiple states are actively considering new comprehensive privacy laws or updating existing laws, and it appears that the definition of “sensitive” data will only continue to expand. At present, three states stand out as the most likely to push the scope of “sensitive” data even further:

- In California, an active regulatory process is underway that proposes to add information of children that are under 16 years of age to the California Consumer Privacy Act’s definition of sensitive personal data, a notable expansion from the other state laws that align with the federal Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act threshold for individuals under 13 years of age.

- In response to concerns about advancements in brain scanning and interface technologies, the Colorado House has passed a bill to add “biological” data to the Colorado Privacy Act’s definition of sensitive data that would explicitly recognize "neural” data, including the activity of the human brain and wider nervous system.

- Privacy legislation is under consideration in Maine that would incorporate the definition of “sensitive data” from the proposed federal American Data Privacy and Protection Act of 2022. That definition includes categories of information such as photos and recordings maintained by an individual for private use, video viewing records, and information identifying an individual’s activities over time and across third-party websites.

Conclusion

Expanding the scope of “sensitive” data, and hence extending heightened protections for new types of information, has obvious consequences for both the individuals protected by these laws and the organizations obligated to comply with them.

However, this trend of defining sensitive data more broadly also raises fundamental questions for the fields of privacy and data protection law. Professor Daniel Solove recently argued in an award-winning paper, that “[i]n the age of Big Data, powerful machine learning algorithms facilitate inferences about sensitive data from nonsensitive data. As a result, nearly all personal data can be sensitive, and thus the sensitive data categories can swallow up everything.” To Solove, this is an existential problem that policymakers must address.

Perhaps lawmakers’ desire to protect individuals through heightened protections for sensitive data is on a collision course with increased technological capabilities. If so, lawmakers could experiment with privacy protections based on harm and risk rather than categories of data. Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), for example, takes a risk-based approach to data breach notifications.

Another potential issue to consider is consent fatigue as more categories of data are deemed “sensitive” and consumers face lengthier and more frequent requests for consent. These laws are just starting to take effect, and the ultimate impact of this approach is yet to be determined. In the meantime, there is little to suggest that the recent trend of an ever-expanding concept of sensitive data will abate any time soon.

Authors