The Illusion of Power: Why Privacy Shouldn't Depend on VPNs and Related Tech

Nina-Simone Edwards / Jul 23, 2024Mullvad, a Swedish company that provides Virtual Private Networks (VPNs)–supplying users with encrypted online connections–has a host of popular advertisements. Many of their ads speak about returning power to individuals or being free from mass surveillance. But what is this power, really?

Although VPNs have existed for decades, advertisements for the service have increased over the past few years as more companies have joined the growing market. Internet users may seek a VPN for more privacy and anonymity when online or if they want to avoid any location-based obstacles. If a user wants to watch a Netflix show that is only available in Canada, they can utilize a VPN to set their location to Canada or any desired region, thereby obscuring their location and online presence. This encryption means that the information is hidden from others who may or may not have malicious intent.

It is true that VPNs offer some privacy protections. Of course, there will always be hackers and those that circumvent the protections, but there is online anonymity and privacy that VPNs can offer. Each company advertises its ability to provide privacy or protection: for instance, ads for ExpressVPN, a Hong Kong-based company, offer the ability to block trackers and malicious sites; the Lithuanian company NordVPN’s ads focus on advanced privacy protection. Curiously, Mullvad often focuses on power.

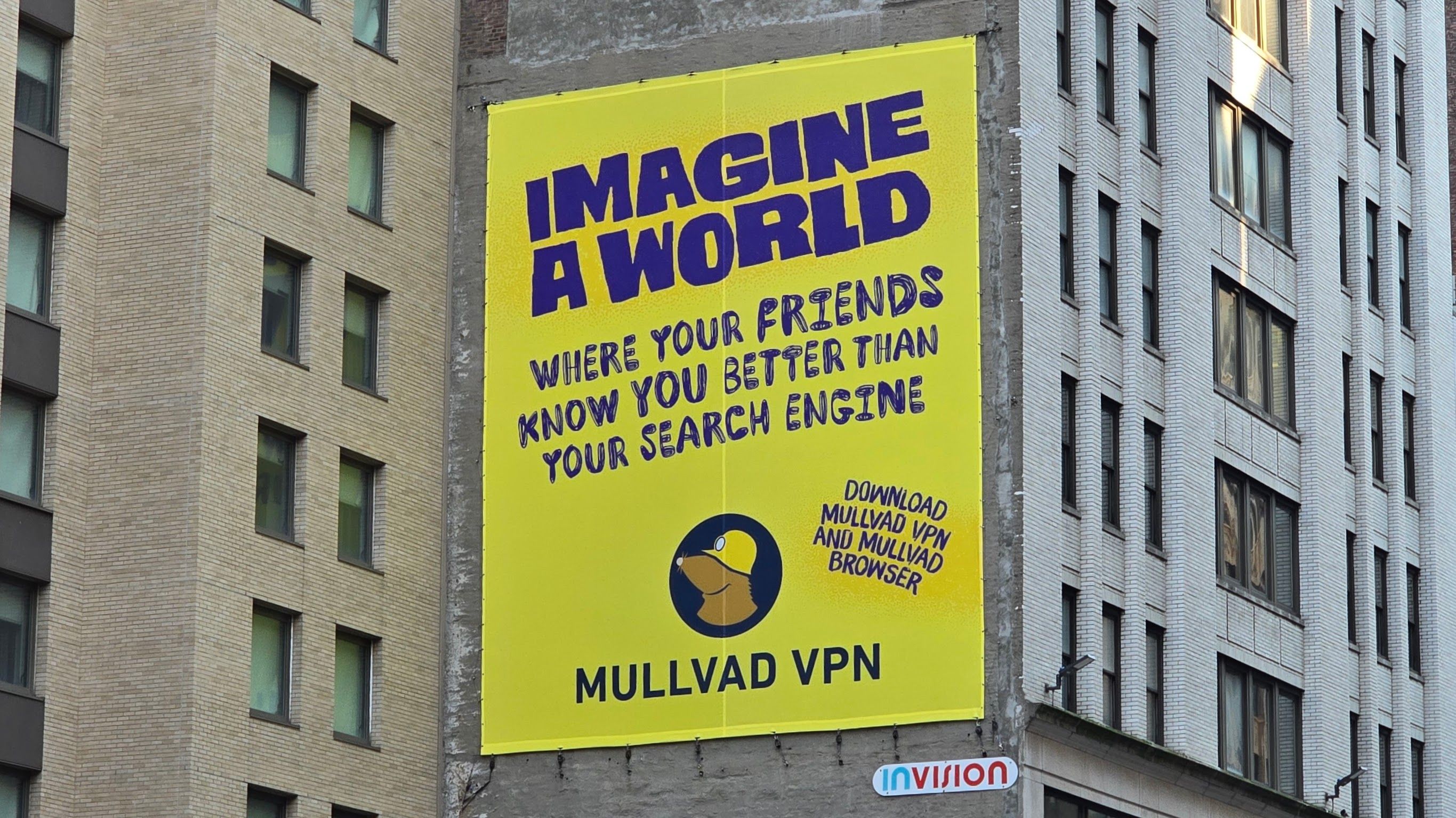

A Mullvad VPN ad in New York City. Justin Hendrix/Tech Policy Press

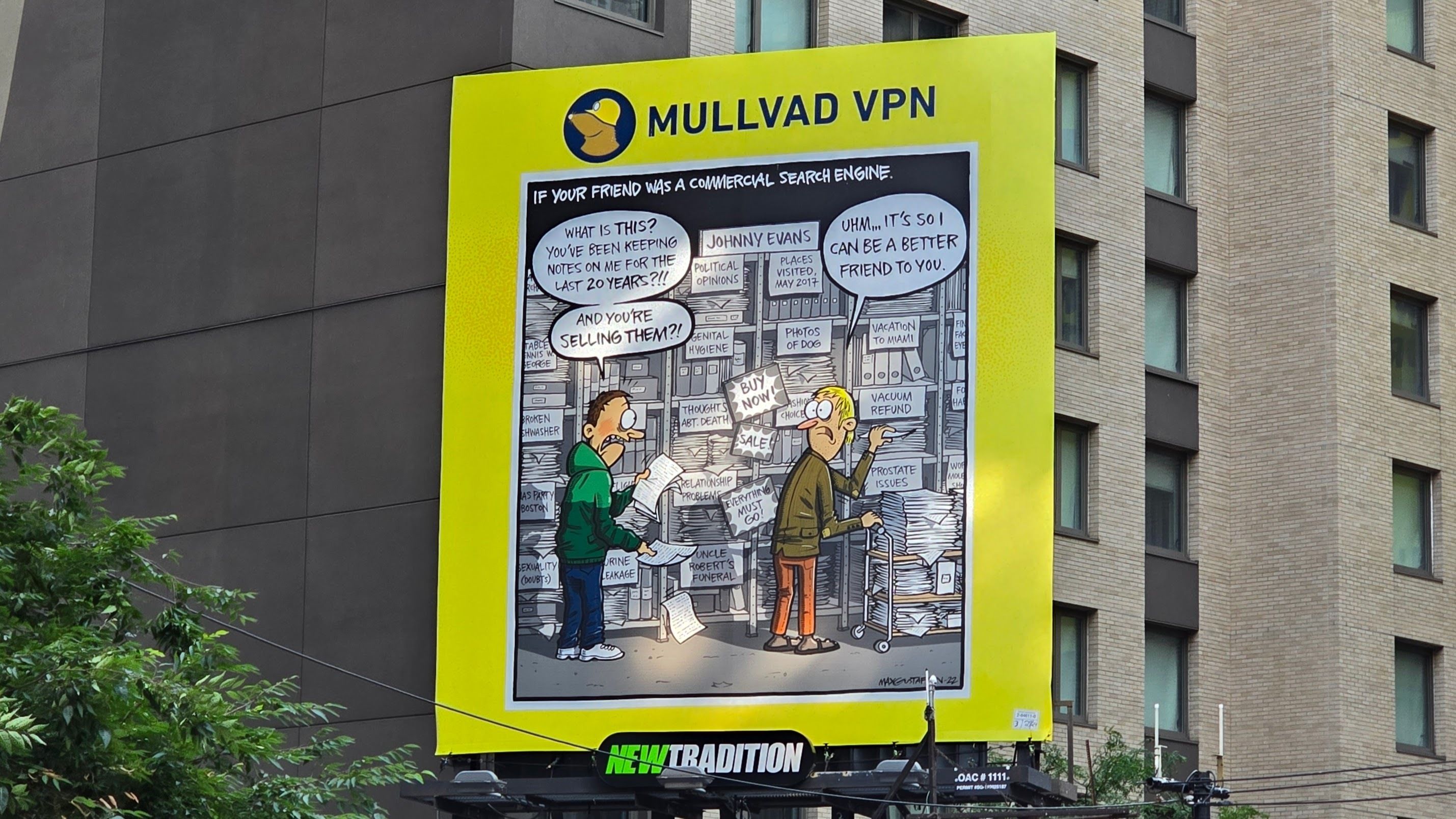

Many of Mullvad’s ads focus on the fact that individuals are, generally, powerless against the collection, storage, and sale of their data. When users get online and use a search engine, everything–location data, personal information, device information, user behavior, content engagement, purchase history–can be collected. A VPN is one way to encrypt that data so that it is not easily accessible. However, this does not equate to the power that Mullvad proclaims. One of their ads states that “you the people have the power,” but while a VPN can obscure some information, that is not the same thing as having power.

A Mullvad VPN ad in New York City. Justin Hendrix/Tech Policy Press

An Over-reliance On Tech–Do We Get Power From Tech Solutions?

Power in this technological age can be interpreted in a few different ways. Here, power is choice, but this concept has changed over time. Thirty years ago, in order to gain an understanding of a consumer’s likes and dislikes to tailor advertisements, there were surveys. Of course, someone could have followed a consumer around a store and noted what they looked at or picked up and returned, but that would have been an incredibly invasive (and annoying) way to collect data. Surveys were probably the best and only way that information was comprehensively collected and analyzed. Regardless of the variety of forms the surveys could have come in, the answers helped advertisers (or anyone, really) tailor their services. The power to simply say no was substantial–if someone did not want to be included in the survey or contribute to the data, they did not have to. Today, in order to gather all of the information one needs to tailor ads and services, a company merely needs to buy data that is already being collected and stored. Unlike opt-in surveys, data is being collected from someone’s personal computer solely because they decided to buy something or look something up.

The solution would undoubtedly be something like a VPN: the opportunity to protect oneself from unauthorized access and collection of data seems like a no-brainer. Yet, VPNs do not truly offer the power that is sought after or even advertised. There is no true choice today as one would have had thirty years ago to say no to a survey. The amount of different services and technologies that someone would need to install to truly shield themselves from unwanted exposure online is extremely daunting–even for more technically capable individuals.

In this way, there is an over-reliance on technology (some would also call it tech solutionism) that has sneakily invaded the consumer and even the policymaker sector. While policymakers are debating and passing state privacy legislation, consumers are tasked with clicking “Ask App Not to Track” on Apple products in the hope that their data will not be tracked and collected. While policymakers fail to enact another federal comprehensive privacy law, consumers seek technology or a service like a VPN (anything from the use of Tor, encrypted apps like Signal, or file encryption services) to encrypt their data. The more tech-savvy consumers may choose to utilize technological solutions involving sophisticated coding solutions. Those without the financial or technological will to purchase privacy tools or to code protections are left at the whim of whatever protections come with the technology they have. Policymakers must recognize that there is a gap between the legal protections being written and the lack of protection in reality–one should not have to invest in, or rely on, specific technologies in order to be safe. Technological solutions are being relied on to fill any gaps that legislation leaves; however, an innovative future should not mean that users are left with no power over their data.

Historically, power–to choose or any other way it can be defined–in the United States could be found in the law (such as the Constitution or intellectual property laws where people have power or protection over their creations). Today, consumers are expected to find their power in the piecemeal of various state privacy laws. In April 2024, the American Privacy Rights Act (APRA) was introduced, with promises of a private right of action. A uniform, federal standard where individuals can fight should they feel wronged is one way to give power to individuals. Another approach could be federal, standardized prohibition of certain data collection, storage, and sale practices. There are a variety of solutions that have been offered in different versions of the APRA (a civil rights section to prohibit discriminatory data practices, the right for consumers to amend or delete their data that companies have, opt-out mechanisms, etc.). This is not to say that consumers do not have federal protections today, but the federal protections (and the state protections, depending on the state) may prompt consumers to supplement the current laws with technological solutions they find for themselves.

Beyond Tech Solutions: A Federal, Comprehensive Privacy Law

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) utilizes its power granted through the FTC Act to protect consumer privacy nationwide. Although the FTC has protected consumers by, for instance, ordering a company to have robust security measures, this is not the same thing as enforcing a law against all companies in a state or country. For example, the FTC may discover the horrific data handling practices of a company, and at the same time, a state privacy law, like the California Consumer Privacy Act, would prohibit similar data handling practices from all companies in California. A federal comprehensive privacy law would ensure the same on a larger scale, but policymakers should prioritize passing comprehensive laws that go beyond the state laws we currently have and any FTC enforcement actions. The recent Supreme Court decision, Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, ends Chevron deference which could also impact the FTC’s rulemaking ability as courts no longer have to defer to agencies if legislation is ambiguous. This in and of itself is a potentially major blow to some of the protections that consumers gain from invasive data practices, which only makes a technological solution even more attractive. Unfortunately, similar to the law, technology is always evolving.

A quick look at the evolution of antivirus software illustrates the futility of relying on technology for protection. In the 1990s, antivirus software was a new and popular concept. People needed protection from attacks and viruses when they navigated the Internet, and antivirus software provided a solution. However, this solution did not last: today, it is not even necessary to have antivirus software because most computers come equipped with protection. Today’s VPN could be the antivirus software of the 1990s; nonetheless, people need the specific protection that VPNs and related technology or services provide. The future will not only provide technological advancements that may be helpful, but it could also hold more danger that will cause people to seek a technological solution. The cycle will only continue without a permanent, standardized solution.

The ongoing discussion of the APRA only highlights the need for a unified federal approach: there will always be disagreements (as seen in the midst of the recent cancellation of the markup of the proposed APRA), but there is a consistent desire and need for a federal standard. Policymakers have a chance to turn the tide and cement protections so that consumers are not forced to rely on technological solutions that will grow antiquated with time. Ultimately, the future of privacy should not depend on the latest technological innovation or the narrow promises of a few pro-privacy companies with limited ability to protect users in an environment dominated by opposing incentives.

Authors