The Most Important Piece of Tech Regulation You’ve Never Heard Of

Dunstan Allison-Hope, Jason Pielemeier / Dec 17, 2024The authors have written this piece in their personal capacities.

Earlier this year, after some significant political maneuvering, the European Union enacted the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D). The result of two years of negotiation, the CS3D is a broad and ambitious law that requires companies of a certain size to conduct human rights and environmental due diligence across their global operations. Those obligations are backed up by regulatory enforcement and civil liability at the EU member state level.

The CS3D builds on the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which came into force in January 2023 and applies to large EU and non-EU companies, regardless of sector (although the financial sector is somewhat carved out). As such, it applies to a broad swath of the world’s most important tech companies, which provide a range of products and services from network equipment to personal devices, search, and social media. As a general law (lex generalis), it complements other, more specific, tech-focused EU legislation, such as the Digital Services Act (DSA), the Digital Markets Act (DMA), and the AI Act. The CS3D echoes key elements of those laws by requiring risk assessment, transparency, and stakeholder engagement while applying to a broader set of activities, geographic contexts, and companies. Importantly, unlike these other laws, the CS3D’s obligations extend to the global operations and impacts of covered companies, and failure to adequately implement those obligations can result in civil liability.

In this post, we unpack how the CS3D applies to tech companies, including the downstream impacts arising from their operations – comparing its scope of application to other relevant tech (and corporate responsibility) laws. We will also explore how the infrastructure of interpretation and enforcement is likely to evolve, examining implications for corporate compliance.

CS3D’s Application to the Tech Sector

1. Understanding the CS3D’s scope of application upstream and downstream

A misperception has emerged that the complex phrasing of the “downstream” responsibilities covered in the law may not cover a wide swath of tech-related harms that result from the “use” of technology. However, this interpretation is inconsistent with existing normative guidance and good practice, as well as the final text of the law and clarifying guidance on CS3D that the European Commission has subsequently produced. Indeed, such an exclusion would be inconsistent with EU political actors’ concurrent focus on significant online “harms” manifesting online and in new technologies, as evidenced by the more-or-less contemporaneous development of the DSA, DMA, and the AI Act.

The confusion stems from language that was inserted as a political compromise in order to satisfy a group of European manufacturers worried about onerous obligations to track and be legally responsible for the human rights and environmental impacts of third parties with whom they do business. To limit this liability, the negotiators restricted the covered activities conducted by companies’ “business partners” to a defined list. They introduced a novel term – “chain of activities” – to describe this set of activities.

The CS3D’s very first Article makes clear that it creates obligations regarding actual and potential adverse human rights and environmental impacts “with respect to [each company’s] own operations, the operations of their subsidiaries, and the operations carried out by their business partners in the chains of activities of those companies” (emphasis added). The term “own operations” is not defined in the law. Still, its juxtaposition with “subsidiaries” and “business partners” makes clear that it refers to activities that a company carries out directly. This includes so-called upstream activities, such as the designing and producing of products or services, as well as “downstream” activities related to their placement in the market and use.

Activities carried out directly or via subsidiaries are contrasted with activities intermediated by a “business partner,” which is defined as any entity with which the company has a commercial agreement (“direct business partners”) or which performs operations related to the products or services of the company absent such an agreement (“indirect business partner”). In those cases, the covered company is only responsible for activities that fall within the business partner’s “chain of activities.” That term is defined to mean upstream activities “related to the production of goods or the provision of services by that company, including the design, extraction, sourcing, manufacture, transport, storage and supply of raw materials, products or parts of products and the development of the product or the service” and downstream activities “related to the distribution, transport and storage … where the business partners carry out those activities for the company or on behalf of the company” (not including products that are subject to export controls).

The important thing to understand is that the “chain of activities” only applies to “business partners,” while all of a company’s own operations are covered, including all direct manufacturing, production, distribution, sales, and marketing. A question then arises as to whether consumers and end users should be considered “business partners” or whether their activities should be understood as continuing to be linked to a company’s “own operations.” While the CS3D does not address this directly, the definition of “end users” and “consumers” found in the draft European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), which were developed to implement the CS3D’s predecessor law, the CSRD, is instructive. Those definitions define both categories as “individuals” and clarify that their activities are not commercial in nature.

Recent guidance issued by the European Commission further clarifies that the impacts of products or services through their use are in scope for covered companies. In response to the question “Which business activities are covered by the due diligence duty?” the Commission clarifies that where a downstream business partner carries out activities “for the company or on behalf of the company,” that company’s due diligence duty only covers “distribution, transport and storage of the product.” It then goes on to state that, by contrast, “[a]s regards the impacts of the products or services through their use, companies in scope are required to identify adverse impacts linked to their own operations, and make the necessary modifications to their business plan, overall strategies and operations, including the design of products/services, purchasing and distribution practices” (emphasis added).

In the same section of the FAQ, the Commission also notes that it understands these obligations “consistent with the approach taken by authoritative international due diligence instruments such as the OECD Guidelines or the UNGPs” (UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights). These foundational frameworks are also referenced explicitly in one of the first recitals of the CS3D. They are generally understood to extend a company’s due diligence responsibilities to potential impacts related to their product or service’s use by end users or consumers. For instance, the OECD Guidelines clarify that “Relationships with individual consumers, who are natural persons acting for purposes that are unrelated to a business, commercial, or governmental activity, are not generally considered ‘business relationships’ under the Guidelines although an enterprise can contribute to adverse impacts caused by them.”

2. Understanding how the CS3D applies to tech companies

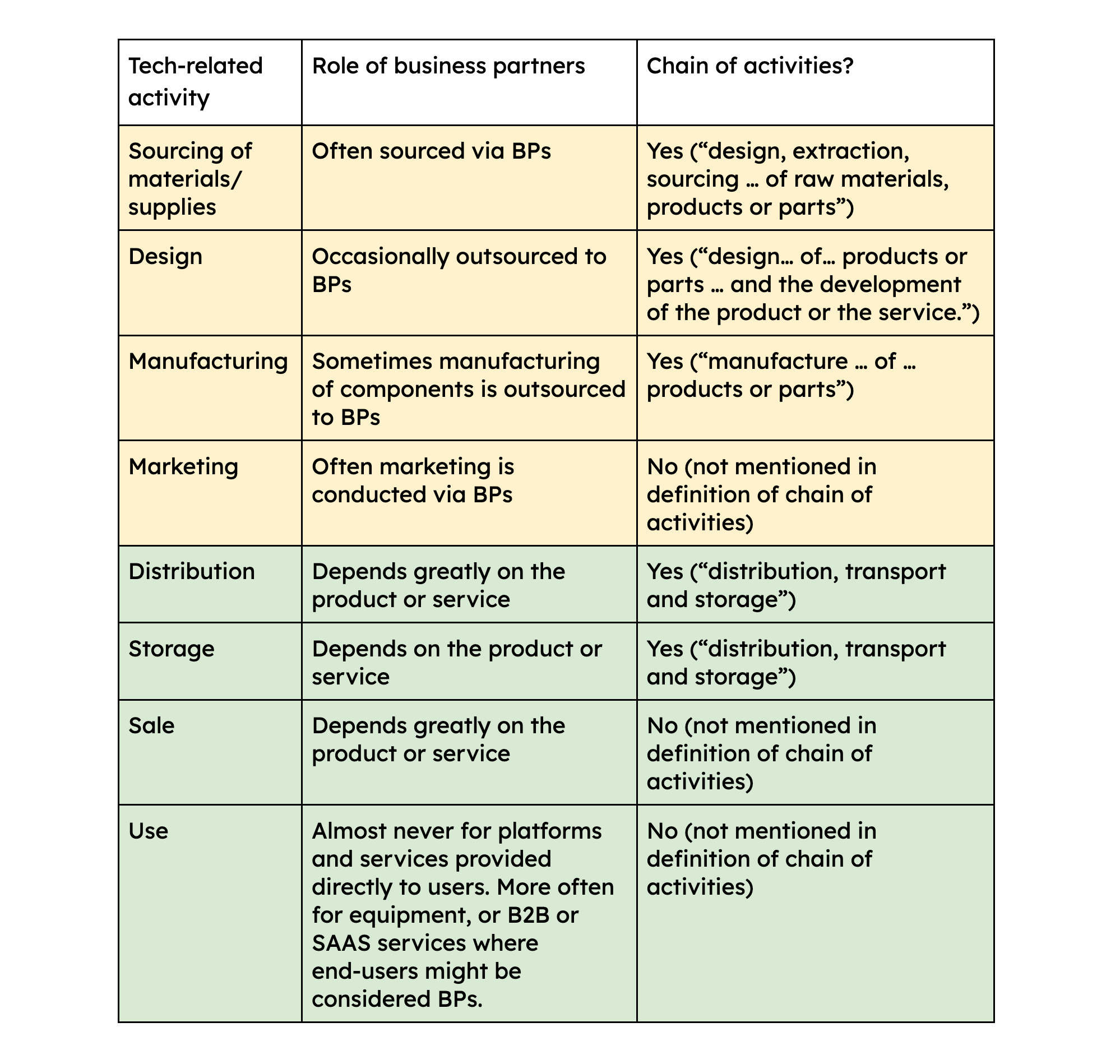

Now that we have parsed the text of the CS3D to understand its scope, it is important to consider how this scope maps to the activities, business models, and products/services of tech companies. The following chart sets out an incomplete list of upstream (yellow) and downstream (green) activities related to a range of tech products and services. It also notes where those activities are often conducted through business partners and whether they would be considered part of those partners’ “chain of activities.”

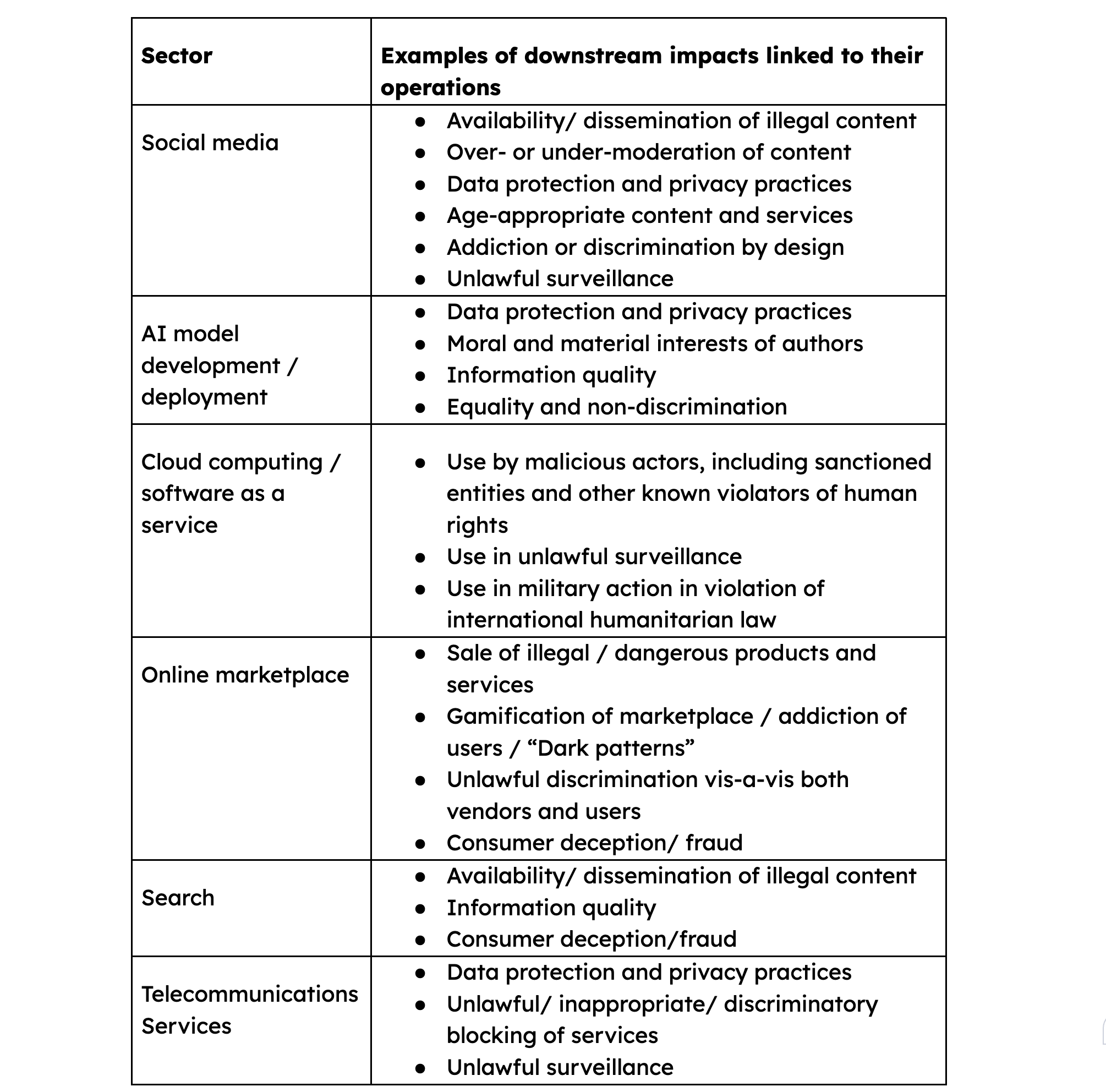

When considering the potential impacts of a tech company’s “own operations,” the term “linked to their own operations” will be important to understand. While the point at which the use of any given product or service ceases to be linked to the operations of a company is likely to be context-dependent, we can envision the following set of incomplete examples of impacts that are likely to be considered linked to tech companies’ own operations:

What should CS3D compliance by tech companies look like?

Tech companies exposed to EU laws face “similar-but-different” compliance requirements, including the CS3D, CSRD, AI Act, and the DSA. To different degrees, each of these requirements utilizes core elements of the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines that companies have long had the responsibility (if not the legal requirement) to implement.

Rather than create bespoke “similar-but-different” approaches to achieve compliance, we recommend that companies establish a single core approach based on the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines from which appropriate information can be extracted to demonstrate compliance with each regulatory requirement. Despite the complexity of the CS3D and other regulations, the same basic requirements and compliance measures can be taken for each, as set out below.

This core approach to identifying, prioritizing, and addressing actual and potential adverse human rights impacts can form the foundation for achieving compliance with specific regulatory requirements. While these steps are conceptually clear, their consistent and appropriate application requires strong internal buy-in and alignment, and specific procedural steps, such as appropriate documentation, executive review, and sign-off. In addition, good practice dictates - and in at least some cases, regulations require - that companies subject their approach to review by external entities, including providing auditors and other relevant independent assessors with the relevant information needed to validate compliance.

- Identify actual and potential adverse human rights impacts (including those upstream and downstream) using international human rights instruments as a reference point since companies may impact any of these rights.

- Prioritize these impacts using the UNGPs criteria of scope (the number of people impacted), scale (how grave the impact), and remediability (whether the impact can be made good), and paying particular attention to the rights of individuals from vulnerable groups or populations, as well as high-risk contexts.

- Identify appropriate action to address these impacts (e.g., avoid, prevent, or mitigate), considering how the company is involved in each impact and the extent of its leverage.

- Track the effectiveness of these approaches over time, including using appropriate qualitative and quantitative indicators.

- Communicate progress addressing impacts publicly, including via inclusion in the company’s mainstream (i.e., public) financial filings, management reports, and/or sustainability reports.

- Use meaningful and effective stakeholder engagement throughout, based on two-way communication, founded upon the good faith of participants on both sides and, wherever possible, undertaken before major business decisions are made.

- Participate in credible, relevant multi-company and multi-stakeholder coalitions that enable system-wide approaches to be taken to identifying and mitigating systemic impacts, especially where no single company can fully address them acting alone.

This last point on the role of industry and multistakeholder initiatives is especially important to note, as the CS3D explicitly identifies such initiatives as a mechanism that can help companies undertake their respective obligations. The European Commission will produce guidance to help companies identify which of these are sufficiently credible and reliable for companies to depend upon but is not expected to create whitelists or blacklists of specific initiatives. Given the extent to which risks and mitigations often extend across multiple layers of the tech stack, such initiatives will be a particularly important mechanism for facilitating CS3D compliance by tech companies.

Conclusion

When reviewing how the CS3D applies to their specific business models and operations, it is important for tech companies to appreciate that the actual and potential adverse impacts arising from using their products and services are in the scope of the CS3D. As a result, they will be expected to make the necessary modifications to their business plans, strategies, and operations – including the design of products and services – to address these impacts.

While there are specific nuances and exceptions provided for in the CS3D, we believe that companies would be well advised to focus on compliance with “the spirit of the law” (i.e., what the CS3D seeks to achieve) in addition to compliance with “the letter of the law” (i.e., what the CS3D actually requires). This approach will position tech companies well for compliance not just with the CS3D but also with other “similar-but-different” EU requirements and other laws and regulations likely to be introduced over the coming years in many other jurisdictions that take the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines as their conceptual foundation.

Authors