The Significance of Tech in the New Atlantic Charter

Justin Hendrix / Jun 12, 2021By August 1941, Britain had been at war for two years. The United States supported its ally diplomatically and with supplies and munitions, but would not enter World War II for another four months. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, in his third term in office, was at the time understood to be on a 'fishing trip' in Newfoundland when instead he rendezvoused with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to discuss the war effort and to lay out a shared vision for the post-war period.

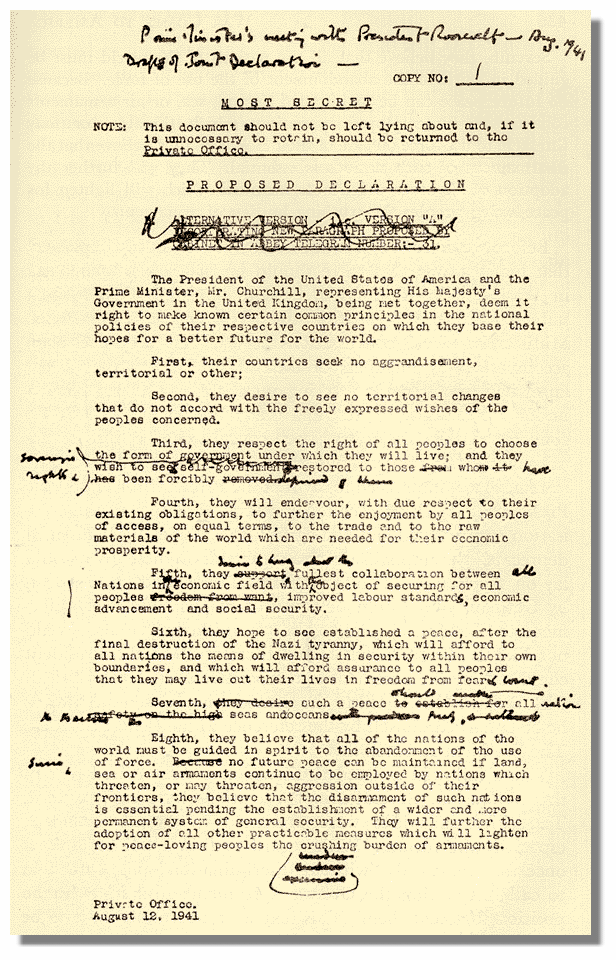

FDR and Churchill aboard the HMS Prince of Wales in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, August 1941: Source

It was at this secret meeting that the two leaders agreed to the Atlantic Charter, a set of eight principles. The Charter had important ramifications- its existence was interpreted by Japan as a potential alliance against it, possibly a calculation in its attack on Pearl Harbor just months later. Ultimately accepted by several countries involved in the struggle against Germany, the charter's principles became the basis for the Declaration by United Nations that formalized the Allied Powers and eventually led to the creation of the United Nations (UN).

"The Atlantic Charter called for self-determination of peoples, freer trade, and several New-Deal style social welfare provisions," writes historian Liz Borgwardt in her historybook A New Deal for the World. "It also mentioned establishing 'a wider and permanent system of general security,' arms control, and freedom of the seas. But this Anglo-American declaration was soon best known for a resonant phrase about establishing a particular kind of postwar order- a peace "which will afford assurance that all the men in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want." Borgwardt observes that the Charter served not only as the basis for the UN, but also prefigured the Nuremberg Charter, which established the tribunal to prosecute WWII war crimes, and the Bretton Woods agreements that created the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

This week, President Joe Biden and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson signed a New Atlantic Charter at the G7 Summit in Cornwall, England. In many ways, the objectives are similar- the defense of democratic values and open societies, international cooperation, collective security, the peaceful resolution of disputes. But whereas the document agreed by FDR and Churchill was concerned with freedom of the seas- the main channel for global trade and arguably still at the time the most important medium for the projection of state power abroad- this new charter focuses on technology:

- First, in its commitment to unity "behind the principles of sovereignty, territorial integrity, and the peaceful resolution of disputes," the New Atlantic Charter also explicitly opposes "interference through disinformation or other malign influences, including in elections" in addition to its commitment to "freedom of navigation and overflight and other internationally lawful uses of the seas."

- Second, the document recognizes that prosperity requires nations to "harness and protect our innovative edge in science and technology to support our shared security and deliver jobs at home; to open new markets; to promote the development and deployment of new standards and technologies to support democratic values; to continue to invest in research into the biggest challenges facing the world; and to foster sustainable global development."

- And third, collective security is not merely achieved by arms and forces in the corporeal world, but must also include "maintaining our collective security and international stability and resilience against the full spectrum of modern threats, including cyber threats."

Further commitments in the document around addressing the climate crisis and strengthening global health systems are also technology dependent. So, will this new charter have similar ramifications to the one penned aboard the HMS Prince of Wales in 1941? Will democracies draw together, particularly on questions around technology, to advance their common interests and those of their citizens?

The document signed by President Biden and Prime Minister Johnson may again precede a range of other important agreements. Politico reports that the "European Union and the United States will announce a wide-ranging partnership around technology and trade next week in an attempt to push back against China and promote democratic values, according to two EU officials and draft conclusions for the upcoming EU-U.S. summit seen by POLITICO." And there is much talk in tech policy circles of the potential ramifications of a "Summit for Democracy", which may take place in 2022.

It is time for big thinking. Globally, democracy has run into a difficult patch, with 2020 perhaps amongst its worst years in decades. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index found that as of 2020 only “8.4% of the world’s population live in a full democracy while more than a third live under authoritarian rule.” In the United States, the twin challenges of a demagogue pushing election disinformation- and indeed inciting a bloody insurrection at the US Capitol- and the fraught public discourse on the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the frailties of American democracy and the information ecosystem that underpins it.

To counter “backsliding on democracy and human rights,” a task force formed last year by American think tanks including Freedom House, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), and the McCain Institute recently released its final report and recommendations for “a New US Strategy to Support Democracy and Counter Authoritarianism.” The report was the product of several expert working groups which put forward “a broad set of ideas to rebuild democratic alliances; strengthen institutions essential to democracy; address the challenges posed by technology; counter disinformation; address corruption and kleptocracy; and harness US economic policy to support democracy.” Tech- often shorthand for the internet and social media platforms in the parlance of the report- is framed by its authors as both a challenge and an opportunity for bolstering democracy that needs to be met with new priorities, organizations, and investments.

It will surely take big thinking to reverse the pessimism many feel when it comes to the question of tech and democracy. Consider the grim views shared by nearly 1,000 expert respondents to survey released last year by the Pew Research Center and Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center. When pressed on the impact of the use of technology by citizens, civil society groups and governments on core aspects of democracy and democratic representation, 49% of the “technology innovators, developers, business and policy leaders, researchers, and activists” surveyed said technology would “mostly weaken core aspects of democracy and democratic representation in the next decade,” while only 33% said technology would mostly strengthen democracies.

In a verbatims alongside the survey, a technology consultant named Kevin Gross identified perhaps the biggest challenge for the decade ahead: “Technology can improve or undermine democracy depending on how it is used and who controls it. Right now, it is controlled by too few. The few are not going to share willingly. I don’t expect this to change significantly by 2030. History knows that when a great deal of power is concentrated in the hands of a few, the outcome is not good for the many, not good for democracy.”

Perhaps it was only coincidence that while President Biden was in Cornwall, Representatives in the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust were preparing five new bills aimed at reining in the power of big technology firms, announced just twenty four hours after the New Atlantic Charter. In a country divided on just about everything, the top Democrat and the top Republican on the subcommittee were singing from the same hymnal. “Right now, unregulated tech monopolies have too much power over our economy. They are in a unique position to pick winners and losers, destroy small businesses, raise prices on consumers, and put folks out of work,” said the Chairman of the Subcommittee, David Cicilline (RI-01), while Ranking Member Ken Buck (CO-04) concurred that “Big Tech has abused its dominance in the marketplace to crush competitors, censor speech, and control how we see and understand the world."

Can world leaders come together to yolk technology to democratic aims? Can a dysfunctional American Congress come together to hold Big Tech to account? Will June 2021 be regarded as a turning point in the years ahead?

The outcome seems uncertain. But then, imagine the challenge facing Roosevelt and Churchill when they met in secret off the coast of Newfoundland in 1941, and all the struggle that was still ahead from that day. It was the right thing then to plot a course forward, based on a few simple principles. Maybe this New Atlantic Charter will have some significance in the decades ahead.

Authors