The Sunday Show: Scoring Social Media Platforms on LGBTQ Safety Issues

Justin Hendrix / Jul 17, 2022Audio of this conversation is available via your favorite podcast service.

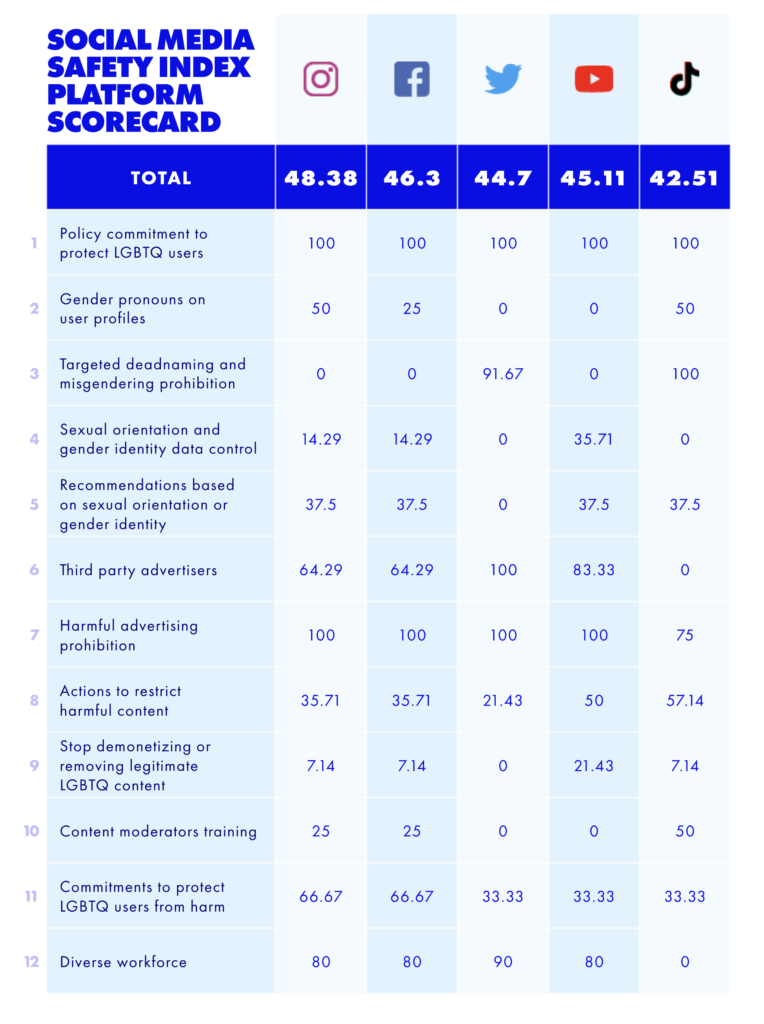

For the second year running, the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation- GLAAD- has released a Social Media Safety Index that finds that major tech platforms are failing to keep LGBTQ users safe. The report was released at a time when the broader social and political context is growing more dangerous- in the US, nearly 250+ anti-LGBTQ bills have been introduced in legislatures this year, even as we see a surge of online hate speech and disinformation about the LGBTQ community, as well as physical attacks.

To learn more about the challenges this community faces in holding social media platforms to account, I spoke to two people who helped author the report and devise the index: Jenni Olsen, Senior Director of Social Media Safety at GLAAD, and Andrea Hackl, a research analyst at Goodwin Simon Strategic Research.

Below is a lightly edited transcript of the conversation.

Justin Hendrix:

Thank you both for joining me. And this is year two, as I understand it, for this social media safety index. Before we get into this report and some of the results, can you just tell me what you set out to do and why this suits the mission of GLAAD?

Jenni Olson:

So last year we issued the inaugural social media safety index report. The idea we had was that we would set out a baseline of the landscape around LGBTQ safety with regard to social media platforms in a variety of categories, obviously things like anti-LGBTQ hate and harassment is a very huge part of the report and what we looked at. But also data privacy, algorithms and AI, all kinds of facets of content moderation, what else? Training of content moderators. Anyway, multiple areas.

In last year's report, we set out kind of what the baseline is and established a bunch of recommendations, met with the platforms and we have ongoing relationships with the platforms around kind of monitoring and rapid response. And then the idea this year was to evaluate them, and get a kind of this LGBT specific scorecard. And so we partnered with Ranking Digital Rights and with Goodwin Simon Strategic Research and brought on Andrea as our research analyst. And so she worked on the scorecard component. I'm excited to hear her talk more about it.

Justin Hendrix:

So Andrea, it might be a good time to ask you a little bit about the methodology and what you all set out to do and how you came up with these figures.

Andrea Hackl:

Yeah, so really in developing those indicators, we look to Ranking Digital Rights and drew their best practices and developed 12 draft indicators to see how tech companies and social media platforms, how their policies impact LGBTQ expression, privacy, and safety, according to those 12 indicators.

And so in terms of methodology development, we first in close collaboration with GLAAD drafted those indicators, received feedback from Ranking Digital Rights, conducted five stakeholder interviews with experts, working at the intersections of tech policy and human rights, as well as feedback from the social media safety index advisory committee. And so based on that feedback, we revised those draft indicators and conducted a policy analysis.

Justin Hendrix:

So let's just quickly, if you were willing to do it, just quickly detail what the 12 vectors are that you were looking at. I think it'd be useful just to sort of list them out for the listeners. So they kind of have a sense of what you were trying to evaluate.

Jenni Olson:

The way that I answer that and like Andrea, in your comment there, you talked about the kind of looking at expression privacy and safety. And they're in these kind of buckets around indicators around public facing policies in terms of protections of LGBTQ users. Buckets around data privacy, particularly around targeting by third party advertisers. And then I don't know, miscellaneous items around training of moderators, options for pronoun inclusion. Andrea, help me out here. What are the other items?

Andrea Hackl:

We also have an indicator addressing prohibitions against targeted dead naming and misgendering, company commitment to diversifying their workforce and then also two indicators addressing targeted advertising.

Jenni Olson:

Right. And I think, so just to jump ahead, talking about and going over these things with the platforms, and we did this last year as well, here's the report, we go over it with them, the draft version of the report, get their feedback on whether there's anything factually inaccurate. And all of the indicators are designed, looking at their public facing policies.

And so there are some examples where they convey to us in certain ways, but not in public facing ways of how they may or may not interpret their own rules with regard to con content moderation. And, I mean, everyone in this field it's like the watch word of the year is transparency. We have no transparency, so we don't know what, how do they make these decisions. And so that is one of the other kind of top level recommendations of the report is there needs to be transparency. How we make that happen is obviously one of the larger questions, but Andrea, do you want to say anything else about that?

Andrea Hackl:

So the other indicator that we included too, was around company transparency around the steps companies take to stop the demonetization and wrongful removal of legitimate content related to LGBTQ issues in ad services.

Jenni Olson:

Let me just jump onto that as well., because that's so important and it is the thing that often gets lost in these conversations because we have so much emphasis on that our request as GLAAD is that the companies do a better job of taking down anti-LGBT content, a content, but that we also want them to stop taking down legitimate LGBT content and that we are disproportionately impacted by those kinds of takedowns. And anyway, it's such an important component of it.

Justin Hendrix:

So I want to kind of get into some of the specific issues and that you raise here, but I just want to pause on the actual scores, which out of a potential score of 100, while you do give each of the platforms you look at, and it's Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, TikTok a score of 100, at least on their policy commitment to protect LGBTQ users. No one on this index scores better than 50% on the 12 indices that you look at. I mean, this is worse than a failing grade.

Jenni Olson:

It was interesting once we had the indicators developed and I thought like, "Oh, they're probably not going to do very well." But I was actually surprised at how badly they did. And I think, there's so much to say. I think the other thing that kind of, back to the transparency thing that is also just missing here, because we don't have transparency is that top line, the first indicator is yes, they actually got 100 on that indicator that they do have policies that say that they protect LGBTQ users. But the enforcement piece, we can't evaluate the enforcement piece because we don't know, we don't have that transparency.

Although if we did, one can imagine they would do even worse given our anecdotal experiences of that. Well, just to lean in on one other specific thing, because with regard to that is the indicator on whether they have a targeted misgendering and dead naming policy or aspect to their hateful conduct policies.

And as we recommended in last year's report, that everyone should follow the leadership of Twitter. Because Twitter instituted that in, I think, 2018. Pinterest actually also has a prohibition against misgendering and dead naming. Targeted misgendering and dead naming. Just to be clear, this isn't if you accidentally misgender someone, this is about really characterizing it that targeted misgendering and dead naming, and is now just an incredibly common frequent method of hate and harassment of transgender people. And so it's a really important policy. And so we recommended that all the platforms adopt that. And we did get in March, TikTok adopted an express prohibition, of course, YouTube and Meta have not.

But our argument is that even if they don't have that policy explicitly, that it actually falls underneath their existing policy and that targeted misgendering and dead naming is a form of hateful expression based on gender identity, which is a protected category in their hateful conduct policies. And these are the back and forth that we continue to pressure them and argue with them and do what GLAAD does as an advocacy organization. But Andrea, do you want to say anything else about this, on this theme?

Justin Hendrix:

There are a couple of other areas, of course, that would appear to be dragging down the rankings here substantially. I mean, one is this sexual orientation and gender identity data control. And another where each of the platforms appear to perform very poorly is around stopping the de-monetizing or removal of legitimate LGBTQ content. Are there anything you want to say about those two in particular where the platforms appear to be performing most poorly?

Andrea Hackl:

In terms of the demonization and wrongful removal of legitimate LGBTQ related content, I mean, there's a huge issue of LGBTQ creators being blocked and demonetized. Which not only prevents them from fully expressing themselves, but also restricting them from economic opportunities. So we would want companies to be fully transparent about how the concrete steps they take on addressing this issue.

And then also in addition to being transparent about the steps they take to address the issue, also disclosing data around the wrongful removal of LGBTQ related content and creators, just to first of all, see what is the extent of the issue and then allowing advocates to track over time, whether or not the issue has improved and whether this content has been reinstated. But yes, as we see in the results, unfortunately there's only very little transparency in this regard.

Justin Hendrix:

You point out a conundrum here. On the one hand you're calling for the platforms to be more, I guess, forceful in their application of their own policies and how to deal with homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, hate speech. And yet you're also sort of course extremely concerned about censorship, censorship of LGBTQ content and expression. I guess this kind of points out what seems to be a conundrum many folks face, which is that these platforms simply don't do a terribly good job of executing against their own policies. And when they attempt to, they make a lot of mistakes.

Jenni Olson:

I was so excited to get to do this interview with you and to go more deeply into this in a way that I feel like we're talking within the field. And obviously this is one of the huge dilemmas. One of my greatest frustrations is that as a field and as a world, we end up having this conversation. And a lot of the times what happens is there's this kind of like, "Oh God, wow. It's like so difficult. I mean oh, well, I guess they're doing the best they can. And like, I don't know what I would do if I was in that position." And then there's this way that it lets the companies off the hook and yes, I get it's difficult.

And I get very agitated about it. Okay, you're a multibillion dollar company, figure it out. And from a consumer standpoint, from other industries that are regulated, fully regulated, are forced to figure these things out and to absorb these costs in particular. And to bring whatever the engineering solutions are to the table. I'm not an engineer. I mean, I do have some background in this. I was on that end of the work when I was one of the co-founders of planetout.com in the nineties, one of the big gay websites. So I get like, it's not easy. At the same time, this is what you built. This is your product, you built it. You need to make a safe product.

If you're in any other industry, there are regulations that say your product has to be safe and you have to incur the costs of making it safe. You don't get to outsource those costs onto society. And I use the examples that the auto industry was forced to install catalytic converters in the 1970s. And they screamed and dragged their feet and "Well, we can't do it. It's too expensive." But our air would be a lot worse if the state of California and then the federal go federal government hadn't forced those regulations.

Or, "Oh, whoops, sorry. We dumped toxic chemicals into the waterways." Oh, well, I guess you're going to have to pay a 10 billion fine. So maybe since there are consequences for that, you will find a solution and again, that industry will absorb those costs. And obviously regulatory solutions, regulatory oversight, those are also very big conversations. And there's lots of proposals out there and many... And we're advocating for regulatory solutions that are carefully crafted and particularly from an LGBT perspective, we don't want to be unintentionally negatively impacted, again. But there is that sense of what we are doing and other advocacy groups are doing is trying to hold their feet to the fire, trying to get public awareness, say they have to do better. They have to do better.

But it's still all voluntary. They can just do honestly, whatever they want. And they're never going to effectively self-regulate as an industry. And anyway, so I start to get very agitated about those things, but I appreciate the opportunity to talk about them.

I just want to say one more thing, which is it's interesting working with the folks inside the platforms. And I mean, our general conversations are all, whatever, confidential. But in a general sense one of the things that we do get back from them is that they are saying, hold us accountable. They are saying that they see the value in this. At the same time, I don't feel naive obviously that they're going to just be like, "Oh, okay. We see all those recommendations, we'll just do all those things." Problem solved.

Justin Hendrix:

It makes sense that you've given an entire page here to just simply listing out the revenues of these social media platforms and their many billions. But maybe on that theme of progress that they are making and effort that they are taking to work with. You have a call out here around the state of conversion therapy policies on social media platforms, how they handle those. And I thought it might be worth just sort of going into that just a little bit, because you've got specific examples here of what each of these platforms have done, in some cases in direct response to your advocacy and potentially in response to at least the last version of this index.

Jenni Olson:

Sure. I mean so just to say we did last year decide strategically that it would make sense to lean into, in these two particular areas, one being the specific language around the urging them to add targeted misgendering and dead naming prohibition. And a prohibition against so-called conversion therapy content. Which is widely decried and including the UN has described it as torture, as equivalent to torture and it's outlawed in 20 plus countries. And can't remember how many states. And it's a horrible, horrible practice.

And we worked with TikTok this past year, and TikTok did add an express prohibition against conversion therapy content. And also actually Twitter added to their ad policy a prohibition against conversion therapy advertising content. And one of the main things that we lean into in the report is all the amazing work of the global project against hate and extremism. They did two reports last year, or earlier this year, going way deeply into the specifically the problem of this content on social media and looking at how widespread it is.

Justin Hendrix:

So I guess just maybe one or two other things I'd love to hit. One of the things that you do detail here as well is the problem of some right wing media, which produce, I suppose, an asymmetric amount of content and problematic content that ends up spreading and ultimately being part of the broader social media content problem. How do you think about that? How do you kind of disentangle right wing media, which are, I suppose-- what's the word I'm looking for-- adversarial to GLAAD's interests on some level, from the broader social media problem, or how do you see them as the same?

Jenni Olson:

Thanks for asking that question. And I got very emotional about this. Let's see how to answer this. I mean, right now in the actual world and on social media, LGBTQ people are under attack and particularly trans folks. But there's more than 300 bills across state legislatures, anti-LGBT bills, anti-trans bills.

And then the attacks in the particularly the last couple of weeks, physical attacks of the proud boys, Patriot Front showing up at gay bars, pride events, events at public libraries. Harassing people, physically, in person. And really terrifying and absolute extremists. And there's a direct connection to social media. There are certain accounts on social media, right wing accounts, not to mention actual Republican elected officials who are... These are people with millions of followers who are bullying and harassing LGBT people on the basis of sexual orientation and gender of identity. Hello, this is in the policies. And so I am furious and terrified. But furious with these figures who are just perpetuating this tidal wave of hate, but then also furious at these companies.

And so this is the thing. Then you get in this like cycle of like, why? Why is it like this? Obviously it's two things. It's the political motivation. And like Sarah Kate Ellis, GLAAD's president and CEO in the introduction to the report, she writes something like targeting vulnerable groups of people as a political strategy is something that we've seen across history. That's what's happening. That is what's happening.

And we are terrified, but everyone should be terrified. And I think people who are thoughtful, intelligent people realize this is impacting everyone. Obviously it's impacting our democracy. It's terrifying for everyone. And we can make corollaries to the 1930s and so it's good to see there are good people who are standing up and who are able to describe what this is. But then the other thing is the money. And that so much of it... There are all these entities that like, you don't even want to name these people or these entities but the right wing media entities where it's a network of like, this is the name of the company and this is our quote unquote talent. These are our people. These are these hate driven personalities, these pundits who are just spewing extremist hate.

And actually Kara Swisher, tech reporter, Kara Swisher, who is on our advisory committee, she has this phrase enragement equals engagement. And I mean, we all know this. It's like, it's why things get... So it's just who can say the most horrible things and that this is going to drive more traffic. But that these media entities are making money. And that they're like subscribe, buy merch... Pay, pay. But of course that the platforms are making money.

And then this is the crux of back to that dilemma. The other dilemma piece here is that they have absolute 100% conflict of interest to not take down hate driven content because they themselves are making money off of it. And there's a million examples of YouTube videos that are totally violative, that have ads on them. And the creator, quote unquote creator is making money and Google is making money and a lot of money. And again, that goes back to the regulatory solutions is like... And it makes sense they're for profit companies, they're not going to reduce their profits. And Frances Haugen has like such great stuff about that.

And it's been an exciting year with the Facebook papers and whatever, and everyone is working so hard in this field/ and I try to have hope, but anyway it's a very scary time.

Justin Hendrix:

It's it sounds to me like you're sort of... And I 100% agree with the way that you've described this vicious cycle which is driven by the economics of our current media and information ecosystem, which seems to be... I mean, of course, bigotry fundamentally is the problem. The first problem, the number one problem, the ever present problem, the problem that was here long before social media. But these economic incentives, these platform incentives, these game mechanics that make it profitable and compelling for individuals to lean into that bigotry and to use it as a tool, to both make money and organize others. I also find it to be an unacceptable circumstance, which is one of the reasons I do the things I do. But it does sound to me like though that you're at least somewhat optimistic that the people close in, the people you're dealing with at the platforms, get it.

Jenni Olson:

Well, I wouldn't go that far. I mean, some do. And I think some platforms, that there are different cultures at the different platforms, and I think some of them do, and some of them don't.

Justin Hendrix:

But at least on the whole, it sounds like based on the grades I'm seeing here and the results of this report, you're not granting that any platform, at least at a leadership level, at a corporate level is prepared to respond to the situation as it is. That very real situation that you're describing on the ground.

Jenni Olson:

Yeah. I mean, I think that is more a function of the fact that they are for profit companies, which it's not surprising. And I mean, Frances Haugen talks a lot about that in terms of like, it's what they're supposed to do is make money for their stockholder. In the case of Meta they're supposed to make money for their stockholders. And I think one of my favorite things to kind of point at point to and that we talk a lot about is that like they do actually have tools at their disposal that they can and do implement at times. And the fact that they can and do implement them at times is a reminder that they're not the rest of the time. That they do have choices.

And of the best example is the, there were a couple of really great New York times pieces about the lead up to the 2020 election and how Facebook in particular did actually implement some kind of speed bumps or friction. Slowing things down in terms of misinformation and coincidentally hate and borderline or low quality content. They want to pretend that it's just like, oh, I don't know. It's just this like neutral landscape and, "God, people are so terrible. And I don't know, we're just this like empty desert. And people are just out there being terrible." But as we know they have very sophisticated algorithms and tools that they use, then they put all their energy into getting us those ads and that they could... Anyway, but the Times piece about the 2020 election lead up was like yeah they were really responsible and hopefully they will be this responsible in the next couple of months leading up to the midterms.

GLAAD is also part of the Change the Terms coalition, we're doing work on that. But then it was like, okay, the election is over. We can turn the dials back to normal. And then what happened after the election. I mean, I was doing this work around January 6th. And I remember messaging to the platforms like, "Okay, I'm setting aside my gay stuff and saying like, here's Stop the Steal groups. Take these things down." Anyway, which they did and which again I get, that these are big jobs, they're big things. And they make less money, but again it's the difference between a safer product and an unsafe product.

Justin Hendrix:

And I suppose democracy or not democracy in some cases.

Jenni Olson:

Yeah. And I mean, these larger level conversations, like we are in a crazy dilemma, the fact that we have for profit companies that are effectively moderating our public conversations. And I get on the one hand that they don't necessarily, in a way, want to be in that position. And like, I wouldn't want to be working at Twitter and have to be the person who is like, literally it's on my shoulders to make a decision, a big decision de platforming some crazy person who is like a huge public figure.

But here we are. And part of that, just to say that's because it's the culture of Silicon Valley. And it's so interesting, the piece that just came out on Monday, the Guardian stuff about Uber. The culture of it is like it's like, how can we basically create a product that is just sidestepping, every regulatory thing that exists? And Uber and gig work, "How can we destroy 100 years of the labor movement progress? We'll just go around it." And so here we are with these essentially unregulated products.

Anyway. I mean, it's exciting to look to the EU and the DSA and to see that maybe the rest of the world can give some consequences to these crazy American companies and TikTok.

Justin Hendrix:

So I want to wrap up in just a second, but there are a range of recommendations in this report, and many of them correspond to the specific indices that you're measuring. So you're making recommendations to particular platforms where they've scored poorly, policy recommendations and the like. But a question I often ask folks on this podcast who are in the business of making recommendations on behalf of any particular group is, if Mark Zuckerberg or one of the other CEOs of these platforms was listening to this podcast, what would be the one takeaway that you'd want them to walk away with from your report? What would be the one thing, the one top line that you'd hope to get across to them? And I'll put that maybe to both of you.

Jenni Olson:

I'm going to say what's coming to my heart. And because I do think like there's something to be said for speaking to in theory to people as people. Which I think about a lot. And I think about a lot really seriously in relation to so all of the companies, they make really incredible statements about their values, which there are values with regard to, in particular, in this instance LGBTQ safety on the platforms.

There's a really great thing that Meta has on their platform about that their values about that people should feel safe and should be free from hate and harassment. And it's a very earnest and beautiful thing. And I would just say, instead of the... I would just say that I would really love for Mark Zuckerberg and other CEOs to look into their hearts and think about their actual personal values with regard to how people should be treated, how people should... And I mean, the truth is that the companies have these actual rules for a reason, so that we can all feel safe.

And I don't mean safe in a quote unquote woke politically, correct, blah, blah, blah, cancel culture kind of way. I mean, that whole way of looking at it has just poisoned the whole conversation. It's just like, we do actually as a society have values about pluralism and about not attacking people for who they are. Which is why the policies exist in the first place.

And there is a line. And I would really hope that they could find a way to take that to heart in an earnest, sincere way. And that's not to be naive and that's not to be contentious. It's just to be like, as people... Just the last thing to say is that we end up stuck in these ridiculous circles of conversation that are predicated on bad faith arguments, disingenuous points that are about honestly hate driven people taking up all of our time. It's the other thing is like, I'm just... It's like go put your... The amount of time and energy that these people put into engaging us in these disingenuous arguments of, I want to be able to say shitty things on the internet. It's like, get a life and stop taking up all of our time with this stupid argument.

It's crazy. Sometimes I think if we spent this much time and energy on something constructive, we could solve climate change. Anyway, thanks for listening. Thanks. End of a TED Talk.

Justin Hendrix:

Andrea, is there anything you'd like to add?

Andrea Hackl:

Yeah, I mean, what I would say is that, I mean, it's really about when companies create these policies and services and products, it's really about keeping their most vulnerable users in mind. And I think a really important aspect related to that is to making sure that the right people sit at those tables and those vulnerable communities are represented in those conversations around policies and products and services in order to make sure their needs are taken into consideration.

Justin Hendrix:

Well, I appreciate the two of you speaking to me today and hopefully bringing some of those needs to the four. And I hope you'll let me know when the next version of this comes out in 2023. I hope perhaps we'll see those scores improve.

Jenni Olson:

Thanks, Justin. I hope everyone will go to GLAAD.org/SMSI and check out the report and yeah, really, really grateful.

Authors