Unpacking China's Global AI Governance Plan

Justin Hendrix / Aug 3, 2025Audio of this conversation is available via your favorite podcast service.

On Saturday, July 26, three days after the Trump administration published its AI action plan, China’s foreign ministry released that country’s action plan for global AI governance. As the US pursues “global dominance,” China is communicating a different posture. What should we know about China’s plan, and how does it contrast with the US plan? What's at stake in the competition between the two superpowers?

To answer these questions, I reached out to a close observer of China's tech policy. Graham Webster is a lecturer and research scholar at Stanford University in the Program on Geopolitics, Technology, and Governance, and he is the Editor-in-Chief of the DigiChina Project, a "collaborative effort to analyze and understand Chinese technology policy developments through direct engagement with primary sources, providing analysis, context, translation, and expert opinion." Webster attended the World Artificial Intelligence Conference in Shanghai. I spoke to him right after his return.

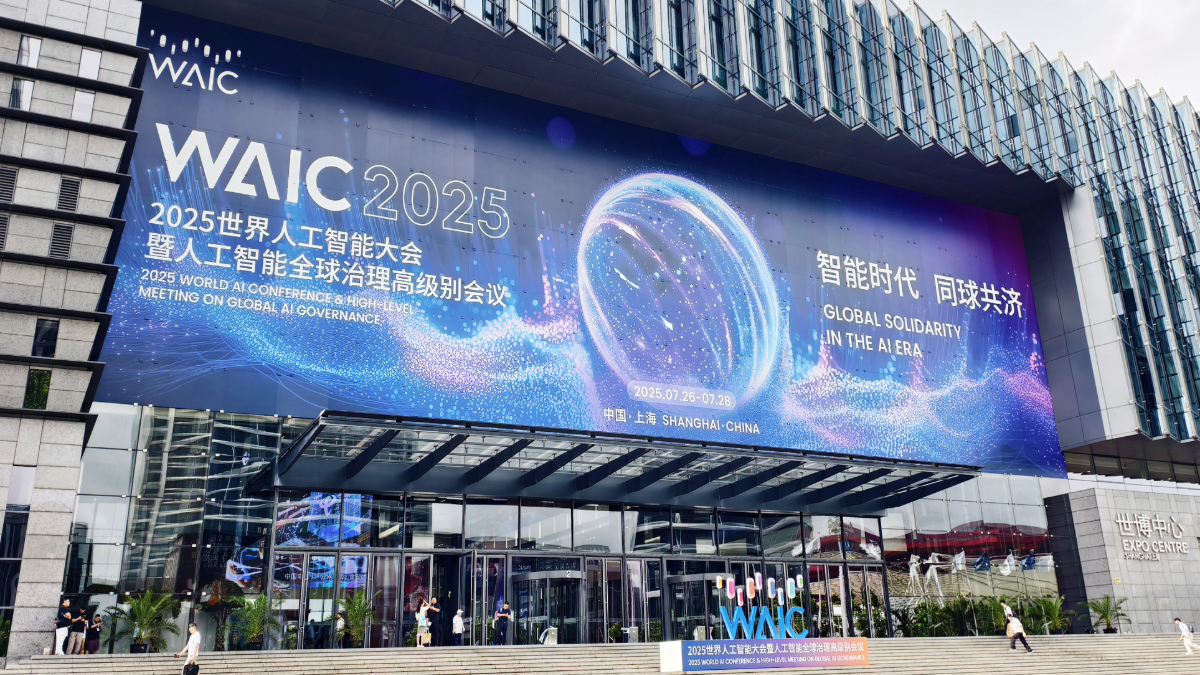

The professional forum of the 2025 WAIC World Artificial Intelligence Conference concludes at the Expo Center in Shanghai, China, on July 28, 2025. (Photo by Costfoto/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of the discussion.

Graham Webster:

So I'm Graham Webster, I'm a lecturer and research scholar at Stanford University in the program on geopolitics, technology and governance, and I run something called the DigiChina Project where we study Chinese tech policy.

Justin Hendrix:

So before we get into this, can you tell us just a little more about the project and how long has it been going and what it gets up to?

Graham Webster:

Digichina has been going for about, I guess we're at about eight years now. It's a network of people from different institutions who've contributed over the years. Originally, we did a lot of just translating the raw policy documents out of China, new laws on cybersecurity and data governance and trying to explain them to the English language world in a way that makes sense and gives some context. In recent years, the translation has been a little less important, but we still have periodic reports that try to go deep on things like cross-border data flows or other specific regulatory topics.

Justin Hendrix:

And you've just come back from China. How long were you there on this trip?

Graham Webster:

I was there, I guess, nine days total.

Justin Hendrix:

Most of that I assume was spent in Shanghai, part of the World Artificial Intelligence Conference that has garnered many headlines, a chance for China to show off its AI innovation in industry and also timed with the release of a substantial policy document from the Chinese government. What was this event like in Shanghai? How would you describe it?

Graham Webster:

This was really a big show. The World AI Conference, as it's called, has been going on in Shanghai for a number of years. A couple of people told me that this year the government took more of a role in organizing it rather than it being mostly industry-led, but there was still a heck of a lot of industry there and it takes place at the World Expo Conference Center, which is an area that was built in 2010 when they hosted the World Expo there. So you've got one big building full of typical trade show displays, really trying to dazzle you with technology. That stuff had, there were a bunch of humanoid robots and dummies of potential robots as well as server racks with blinking lights and showing the new Huawei gear. And as well as booths for individual companies talking about applications, there was one for the national weather forecasting authority, had a whole booth about how they're going to use AI to do different types of things.

And then on the other hand, in a more typical kind of convention meeting type of format, there's another building that was full of what they called forums, which were basically panel discussions or a few big plenary sessions on different topics with people. And those really ranged, it was from the stuff that I was there to participate in and observe was mostly about policy and sometimes the AI safety or security related concepts, but there was also stuff on industries and various types of applications of machine learning technology, green tech, FinTech. I think there was one on power infrastructure, stuff about data resources and supply chains. A lot of talk about agentic AI.

So in a way, it's part of the same industry/policy verve that we have around the world. And so if it's ... The stuff that in retrospect may turn out to be hype was definitely there and the stuff that is signaling ways in which people are going to use big AI systems is also there, but it was heavily China-focused, lots of Chinese there, quite a lot of people from around the world as well. I don't know. Vast majority looked to be Chinese attendees.

Justin Hendrix:

And I do understand that some of the kind of, I guess we could call them AI luminaries as the Financial Times refer to them. Folks like Yoshua Bengio, Geoffrey Hinton, Eric Schmidt were there as well. How would you characterize the kind of US or Western participation in this event?

Graham Webster:

Yeah, I don't have an overall picture of that, but that's right that there were a number of big names that came from the US and the UK. Especially in the conversations framed around the concept of AI safety, we're really several years now into an effort by people both in China and abroad to have that safety conversation be a cross-border one. And it's pretty easy to understand that if you believe that there are existential or catastrophic risks coming from AI development, and you've observed that China is one of the places developing big AI models, yeah, you're concerned about what's going on there as well. But there were also people, I didn't ask for passports, but there were people who looked foreign who I think may have been just looking to do business and figure out what the Chinese companies were up to.

Justin Hendrix:

So of course we've spent a lot of time on this podcast, even in the last couple of weeks talking about AI policy in the United States and Europe. And of course much of the debate about AI policy in the US these days is framed in contests with China. It's framed as this race that we've got to win, and that seems to be motivating a lot of the bigger headlines that we've seen over the last few weeks and months from the federal moratorium that was proposed in the budget reconciliation bill. A lot of what appeared to be motivating the individuals who supported that was this sense that we need to throw off the shackles in order to ensure that we win the race with China.

More recently, of course the Trump AI Action Plan framed in similar terms, this idea of American dominance running through that and through the intent there, trying to get most of the world on American technology, on the American technology or AI stack as it were. I don't want to necessarily make this conversation entirely a comparative one, but I don't know what, did you get the sense the mood in China is when it comes to what it's trying to do? Are they seeing things the same way right now? Is it so US focused there? Is it very much this kind of race mentality?

Graham Webster:

It's a really mixed bag on that because there's definitely a consciousness among people who are from companies or trying to develop large models or who are in the broader AI policy ecosystem. They know that US policy is specifically on semiconductors, has been designed to hold back China's progress on that. So there certainly is a kind of direct competitive consciousness, but that's the background condition of reality. And another reality that's quite vivid is that you have very powerful comparatively on the metrics that people monitor, very powerful models coming out of Chinese labs. So we all heard about DeepSeek, had a really big splash in January. The Alibaba Qwen, as they call it in English or Tongyi Qianwen in Chinese models, are rated very highly and they keep coming out from different firms including Moonshot AI, which released one just over the last couple of weeks. There's both a sense that the US is trying to hold China back and there's this direct competitive element that's implied there and a sense that China's actual production of AI widgets is not so far behind at the moment.

And then the part that's not competitive or that just is a different mentality I would say, is that China's government, and to some extent business discourse over the last several years has been more focused on applying AI systems, machine learning techniques to upgrading various types of industries. And so that type of real development-focused logic I just think is louder in the ... When you go into a space labeled AI in China, you're going to hear more about manufacturing or power system optimization than you might hear in a US space labeled AI where you're going to hear more about large models and catastrophic risks and the potential for an AGI or superintelligence kind of everything machine that might be forthcoming. I do think that there's ... Yeah, they have that competitive view, but it's not the centerpiece I think, and it certainly wasn't the centerpiece for the government's global governance plan that they released at the conference.

Justin Hendrix:

So let's talk about that for a moment. Can you just give us the outlines of what they released and what it's for?

Graham Webster:

It's called the Global AI Governance Action Plan, and this is something, this is a document that was released by the Chinese government. It was effectively announced by Li Qiang, the number two leader, the premier in China, who was the keynote speaker at the opening session, which peons such as myself were not allowed to get into. So this document was, it's really about an inclusive vision of AI governance that focuses on institutions like the United Nations taking into account the realities of, for instance, the Global South, talking about the UN SDGs, the Sustainable Development Goals. It talks about building out AI infrastructure around the world. They're also interested in moving data across borders for artificial intelligence purposes. So there's this mention of "Collaborating to facilitate the lawful, orderly and free flow of data," and they propose a global mechanism or platform for data sharing. There's some stuff about sustainability in there and there's some sort of conflicting ideas that I haven't quite been able to make sense of.

They're quite in favor of open source, but also they repeat this very common Chinese regulatory language about keeping technology secure and controllable or safe and controllable. How do you keep things open but also controllable is not totally clear. But finally they proposed this "Multi-stakeholder governance model," which I find interesting. It's a contrast with China's traditional emphasis on multilateral internet governance, meaning governments only, whereas multi-stakeholder includes non-government characters. So overall, it's a really cooperative, open type of pitch that would be collaborative with many governments and others around the world.

Justin Hendrix:

And how would you compare it to other tech policy statements? You've already indicated that it is this kind of collaborative, multilateral, open, these are words that you've used. How would you characterize it in comparison to say Chinese internet policy or policy on other technologies?

Graham Webster:

Yeah, a lot of this rhetoric is really familiar. Periodically in the last few years you've had the foreign ministry release these, I'm going to get the precise terms wrong, but the global initiative on cybersecurity or the global initiative on data security, and these are kind of uniformly documents that emphasize the sovereignty of individual states and the sort of mutual respect among them. A bunch of these types of principles appear in the new Global AI Governance Action Plan as well. I think where it's a little different is there's a slightly more specific focus on some mechanisms that might be proposed. It's pretty fluffy language. It doesn't commit the government of China to doing anything in specific. It didn't come out with other governments or organizations signing on to support it. So if anything, there are indications there for people who watch Chinese policy initiatives and it may point to what they'll try to accomplish in the next few years, but a lot of it is vibes-based I think at this point.

Justin Hendrix:

How does this plan seem to comport with China's kind of long-term vision of its role in the world or its intent on the geopolitical stage?

Graham Webster:

Yeah, I think that's a fair question. It's a document that reflects some pretty long-standing Chinese diplomatic stances, solidarity with the developing world, the idea that Chinese development models could extend around the world and help lift up others. The focus on the United Nations is very continuous with the Chinese diplomatic stance, the high-minded version as well, the United Nations is the thing that everybody's a member of. The more hard-nosed version is that China is a member of the Permanent Five in the UN Security Council, so they effectively get a veto of anything that goes on at the UN, meaning it's a preferred venue for many things that if the world is going to decide to do something, they'd like to do it within the realm of someplace that has a Chinese veto.

Yeah, I mean I guess it's unsurprising as a China observer, as somebody who studies China's policies that it all is pretty continuous seeming. It's unlike the US where we swerve drastically between policy stances, this is a document that's put together by a group of people who are working in the context of decades of continuous rule by the Communist Party and the government, and at this point, more than 10 years of Xi Jinping's specific rule. So yeah, it is coherent for whatever that's worth. I think that may be worth something diplomatically because governments don't expect drastic changes in approach from the Chinese side, but that doesn't mean that if the deal that the Chinese government was offering or promoting before this document wasn't of interest, then it still wouldn't be of interest. So it's a mixed bag, but it really is ... If you read this alone, you won't get the nuance of all of the stuff that the diplomats have been bashing on about for 15 years, but you'll get a pretty good idea of what some of the other documents do say.

Justin Hendrix:

I do want to turn to the Trump AI Action Plan, which some folks framed the China's release of its document as somehow a response strikes me that's probably unlikely that this conference was planned for a long time. They intended to get it out. It was just a kind of coincidence that these two things came at the same time. Nevertheless, it's useful to perhaps compare them. The Trump administration gave us a 28-page AI action plan and re-executive orders, which lay out some of the intent of that plan. In your read of it, what stands out to you, particularly comparatively to what China's trying to accomplish?

Graham Webster:

It's really interesting that these things came out so closely together. I think it's probably a coincidence, but I do sometimes ... Action plan isn't always what the Chinese government will call its things. And so I wonder if there was some anticipation that the Americans would be coming out with an action plan and so maybe it would be nice to have a Chinese action plan rather than the five other diplomatic proposal words that they could have used. But substantively, that's where the contrast is much more vivid and I'll talk about it just on the limited ... I haven't read the executive orders.

I've had time to study the action plan document itself from the Trump administration, but I haven't gotten into the full packages. I know you have on the podcast and elsewhere, but it's a stark difference with the Chinese document being really collaborative and inclusive in nature and talking about doing things at the UN versus right on the cover, you have an adversarial frame from the US plan, which you've got, "Winning the race" right there above the title of the thing. And right throughout you have references to things like global dominance and keeping adversary technology out of the United States. China's mentioned quite a number of times in the Trump plan, but there are a lot more times when it's not named, but clearly if you're going to win the race with somebody, they're talking about China in this case.

There's actually some parallels I thought. There's encouragement of open models in both of them. There's support for industrial upgrading and I think some consciousness of the risks of job displacement in either both documents or certainly that's present in both countries' policy discourse. There's a sense of reaching out to other countries that is slightly parallel. In the US, they're talking about a like-minded alliance. In China, they're talking about a global, especially Global South, widespread set of mechanisms to try to figure some things out. But yeah, the US effort is framed around beating China and dominating the world, whereas China's is framed around, let's do this together and see if we can figure out how to balance security or safety versus development globally with some sort of more collaborative regulatory approach.

And just beyond the individual documents, it's really important to note that China has a pretty robust ... I mean it's not totally comprehensive, but it's a quite coherent regulatory structure around current uses of generative AI. There's a whole data governance set of regulations, there's a whole field of regulations around using ICTs in the critical infrastructure, government roles and other things like that, whereas the US emphasis is basically on let's deregulate or not regulate and build and only get any sort of barriers in there only where it has to do with dominating or beating the adversary.

And I think that's a pretty vivid difference, which raises to me, I ended up thinking like, okay, if you have China proposing this big international effort to try to meet some of the challenges that come from these technologies and then the US basically saying these companies shall be set free, I'm not sure where there's any leverage to actually regulate the Americans. You might be able to discipline a bit what the Chinese companies do and individual states outside of the United States might be able to circumscribe what the Americans can do there. But if you're worried about emergent existential risks, which I'm quite agnostic on whether this is a serious issue. I just observed that a lot of people are worried about that. You're not going to contain that if the Americans are just letting it lose.

Justin Hendrix:

What more can you say about the kind of domestic AI governance circumstances in China? Here we're having this argument about whether states can play any kind of role. Is it all top-down national level regulation in China or is there a more complex picture that those of us who aren't terribly familiar with how things work there need to understand?

Graham Webster:

The Chinese context is mostly central for AI relevant regulation. Fundamentally, it's based in what I call the three laws, the cybersecurity law, which went into effect in 2017, and then the data security law and the personal information protection law, which I always mix up. I think they went into effect in 2021. But these set out a bunch of obligations for network operators or people who handle and use data in various ways that then have these downstream effects on things like generative media or recommendation algorithms.

So it's a contrast from Europe, for instance, which has the EU AI Act with all its complexity and kind of uncertainty about how that's going to be implemented. In the Chinese case, you know that you're not allowed, for instance, to discriminate in terms of pricing based on personal data you've collected from your customers. There were reports I saw online about US companies trying that, trying to see if they can charge somebody more because they have this sort of surveillance tech, their surveillance capitalism type of data suggesting that I might be willing to pay too much for a photography book because I like photography books. Maybe they'll just charge me more. That's just simply illegal in China, it's enumerated, you're not allowed to do that.

There's also a bunch of stuff that in terms of what they call deep synthesis, which was intended to address deepfakes or deceptive generative AI, and then also more recent generative AI, which came out after the advent of ChatGPT where there's a lot of really detailed requirements there. But the intention is to maintain the integrity of the information space from the Chinese state's perspective, which means some stuff that we would recognize as legitimate public safety and civil law interests, and then the stuff that you would expect, which is political censorship and controlling discourse and making sure that you don't foment rebellion or say things that you're not allowed to say about what happened in 1989 or call Xi Jinping an idiot or what have you.

This is all there and it's all kind of being enforced in various ways, and the providers of models and AI services and the users of other machine learning in China are used to it. It's the background, and this stuff has been there for years, and it comes with various sort of enforcement campaigns. There's one that they announced a thing called the Clean and Bright Campaign every year, the Qinglang Campaign. And the one this year is about making sure that AI generated content is labeled when basically influencers, what's called zimeiti 自媒体, or kind of "me" media, self-published media sources like influencers, make sure that they comply with rules that say that you must label generated content and this isn't some profound bit of encrypted embedded labeling of images. It's, you have to have a conspicuous label that says that this was AI generated and that's just the rules now. And so now they're going out and they're trying to enforce that.

But it also puts it on the platforms. The Chinese domestic equivalent of TikTok called Douyin or if you're another similar platform, they're expected to create mechanisms that will both make sure that if a user uploads something and then they label it as AI generated, that it remains labeled as it goes around the platform. And they are expected to try to detect if there is metadata that suggests that it was generated media or if there's other detectable hallmarks of generated stuff. It's really a quite widespread set of regulations on various uses of machine learning and generative media that all the major players in China are used to. They're also used to using machine learning for detecting illegal discourse to accomplish their censorship obligations. I just find that there's a lot to disagree with about, especially in the area of censorship, but it is a robust and kind of coherent, interlocking developed already operating AI regulatory space.

What it doesn't really have is the sort of future frontier-based stuff. There are a lot more hands off at the moment, and in terms of regulation, a lot more kind of agnostic about whether there's going to be large scale risks. Certainly there's nothing that's seriously contemplating existential risk from some big LLM system that turns into a superintelligence. But there's also a kind of cautious stance on constraining things like, so one of the hot topics at the Shanghai Conference from various sides was the potential misuse of models to produce harmful biological materials in the way that a combination of generating DNA strains and then the ability to fabricate those strains could get bad. There's a more cautious stance on that, although then if you want to go to the people in China who will fabricate some DNA for you, I don't know exactly what their structure is, but they're going to be under some sort of biosecurity regulation as well. There's a whole biosecurity law that exists.

Coming from the US where we don't have centerpiece data privacy legislation, you do have a kind of patchwork state by state. It's much more built out in China at this point and mostly centralized. There's a few sort of experimental zones and different free trade zones for things like cross-border data flows and self-driving experiment zones and that type of thing. But fundamentally, the overall rules are national and pretty established at this stage.

Justin Hendrix:

I know you don't necessarily want to speculate on things like superintelligence, and we've had Mark Zuckerberg just yesterday releasing what looks like a kind of mini manifesto on superintelligence and Meta's vision for that, for instance, that appears to be where most of the big tech firms want to head into AGI or superintelligence or something that they can claim is smarter than a human. But I don't know, did you walk away from this event, either the policy level discussions or anything that you saw at the congress that gives you any insight into what the of achieving that type of threshold might be for the kind of competition as it were between the US and China?

Graham Webster:

Yeah. It's a tough question. One of the things that I struggle with here is the terminology around it. The Zuckerberg statement I thought was really funny because when Meta announced that they were going to be doing superintelligence, I thought, oh wow, they're really going for it. They think they're going somewhere and then you read what he's talking about. And it's been a long time since I went through that Nick Bostrom book, which I think popularized the term or may have coined it, but there that's talking about ... The Bostrom "superintelligence" is like the thing that's going to gobble up the world and maybe it would be benign, but more likely it will destroy us all, and then you got Zuckerberg talking about, "We just want to use all your personal data to create this customized environment to make you more productive." And this is Microsoft Word on steroids. I don't know.

So I think even just in the US there's a confusion about what is superintelligence or AGI or whatnot. I think there's a heck of a lot of confusion between the English language world and the Chinese language world about AGI. The term that is commonly used in Chinese for this translates back into English as general purpose artificial intelligence. And so the distinction is between specialized systems and systems that may be useful for unanticipated things, general purpose. That captures some of the concept of general intelligence, but it doesn't capture this threshold of what I tend to call the Everything Machine or the God Machine, which some people see forthcoming, which would be this sort of inflection point.

And I think there's just a lot of different views in China about what general purpose AI might turn out to mean, and some people certainly, I think it's pretty well documented that the head of DeepSeek, for instance, is looking to build Everything Machine, but a lot of other people are just like we've got, "Okay, LLMs are general purpose in that I can apply them to a bunch of different things. And so it's useful if I have access to an LLM that seems to be useful in a bunch of different contexts, cool, I will use it. I'm not worried about the future of humanity."

So I think that confusion is just very deep for me, and I didn't come away from Shanghai with that cleared up except to say that I'm more confident in my sense that the views on those terms are quite diverse in China, and it would be an error to take any given use of that. The typical Chinese language term for AGI, if you translate that back to mean the Everything Machine or the singularity or superintelligence of the Bostrom sense, then you're going to be confused. We just have to be much more modest and ask follow-up questions about what people mean.

Justin Hendrix:

Absolutely. And we've of course introduced a lot of skepticism about these ideas on Tech Policy Press and certainly in this podcast in the past. And yet I still think it's worth thinking about what these ideas and the argument over these ideas or the possibilities of something like a superintelligence or an AGI, how those seem to be animating the policy debate effectively. There was a hearing on Capitol Hill in the House of Representatives Energy and Commerce Committee in April under the title Converting Energy Into Intelligence: The Future of AI Technology, Human Discovery, and American Global Competitiveness, where Eric Schmidt, the former Google CEO, was one of the witnesses alongside Alexandr Wang from Scale AI. And one of the representatives, Cliff Bentz, a Republican I believe from Oregon, was asking about this race with China. And he put the question to the witnesses in different ways, but at one point he turns to Eric Schmidt and is asking, "How do we communicate the race to the American people? How do we help people understand what's going on here?"

And so the witnesses are trying to find clever ways to communicate the race, and Eric Schmidt came out with this phrase or this set of sentences that ended with this rhetorical question, which I'd be interested in how you might answer actually. So what Eric Schmidt said was, "In 5 to 10 years, every American citizen will have the equivalent of an Einstein on their phone or in their pocket. This is an enormous increase in power for humans. What if that Einstein is a Chinese one?" Pause for a moment. I think that there's something deeply xenophobic in that question that we could probably examine in different ways, but what if that Einstein in our pocket is Chinese? What in the world would that mean?

Graham Webster:

Yeah. I remember that quote when it came out and I'm just going to, at the outset, I want to say that I don't necessarily think that's happening. There's a bunch of stuff about it that just doesn't work for me. One, if it's supposing that you've got systems that are superior or Einstein-ish in capability, there's all these things about what is intelligence? And is it computational in nature? And et cetera, et cetera. And I just am skeptical about that. And I'm also skeptical that you'd put it in your pocket and have enough power to run it there if there was such a thing.

Now, setting aside my skepticism of the general proposition and accepting that highly capable text extrusion machines and systems built around them may indeed come to be, yeah, what if those are Chinese made? And I think there are some relevant things here. One is the Chinese government does regulate the way that the interfaces of chatbots are constructed. For instance, with DeepSeek, if you go to the DeepSeek app or if you go look at Doubao, the one from ByteDance or et cetera, these are designed not to tell you things about things that are politically sensitive in People's Republic of China history. They're censored in that interface.

Now, the underlying models, the sort of weights themselves at the sort of math level, the embodied digital object that is the model may or may not have all of that training in there. And you see Perplexity, an AI company based outside of China trying to sort of de-censor DeepSeek's models and offer those for people to use. So whether they're durably censored or not is also a question. But yeah, I do think it is relevant if you have a regulatory structure that is focused on discourse control and avoiding certain political outcomes that has its thumb on the scale of however your information systems are built.

And at the same time, you have to think through what are the actual concerns that you have with that? If you're getting the benefit of having an extremely useful tool, are you really concerned that it's not going to be useful for you in understanding internal Communist Party discord or the specific history of human rights abuses in China? That's a downside, but he's saying 5 or 10 years, I don't want people going around believing what these machines tell them today, let alone in a decade. I'd hope that by then we're a little more skeptical of the probabilistic and chaotic output of these things. And if anything, I would hope that societies and governments would sort of figure out ways to either coerce or otherwise push the people offering these types of products to have them not be holding forth as confident in things that they actually cannot be truthful about. There's all sorts of problems that I have with it.

But at the end of the day, if I'm trying to do my math or I'm trying to do my vibe coding or whatever, it doesn't matter if it's Chinese, it doesn't. I just think there is a xenophobic thing there.

The bigger issue, which actually is more ... Schmidt has stronger arguments about this stuff and not that I agree with him. He's at the center of a community of people who are concerned that if Everything Machine and superintelligence inflection point occurs, then that machine will be usable in ways that can significantly upgrade military capabilities and intelligence capabilities and counterintelligence capabilities and offensive cyber capabilities and defensive cyber capabilities and all these sorts of national security, geopolitical competition crisis relevant stuff. And as I've said, I'm agnostic about whether this massive inflection point is coming, but if there is some really big moment, yeah, I'd buy it. I don't think it's controversial to say that militaries would use this stuff and leverage it quite well.

So if you're sitting in the Pentagon and your concern is that there might be a war with the other great power on Earth in the coming years, yeah, you're concerned about that and that's totally reasonable. It's your job. So would you prefer that type of critical moment occur in your country or in an adversary country? Yeah, you'd want it to happen at home. I don't think that's all that controversial. What's controversial is for me is this magical moment coming? I really think that's a big bet. I think that if the magical inflection moment comes, that blows everybody's minds, there's also this kind of insane assumption that it will remain under the control of its developers, which is not what a lot of the people who are concerned about AI safety think would happen.

There's also a sense of if it's created by OpenAI or Anthropic, that would mean that it is American in character and would be a democratic AI, which I think is completely nuts. The idea that just because something is made in the United States, it's democratic. That's not really even what we're doing with our currently democratically elected governance. That's bonkers stuff. So it really has to be specified to what you're actually concerned about. If you're concerned about military applications of AI, yeah, that's real. And this is where I part ways with some people who say that all of this is just total crap and who say that there's some people who really don't want to see US-China relations as a sort of geopolitical competition, but you know what? The militaries are building capabilities that are aimed at potentially fighting one another. That's just actually happening. So you've got to think about it. You can tell I think it's a complicated thing, and policymakers have to make bets.

The last thing I'll say is Eric Schmidt went to China. He was there at either at the WAIC or at some related meeting and reportedly was making the pitch that some of these safety issues when it comes to highly capable AI models actually need US-China cooperation. And so I think that's interesting. I think it's obviously true if you believe that there's these really capable things coming and that dangerous capabilities are already coming online, whether it's for the lowest hanging fruit being helping to automate cyber offense and this type of thing, and the proliferation of that being dangerous for cybersecurity defenders in governments and firms and critical infrastructure and all that. That's a real thing. It would be nice, and it's a common interest that the US and Chinese governments and peoples have to avoid various types of mayhem becoming a lot easier to produce by all kinds of different actors states and non-states and groups of nerds in basements and so on.

It's just a complicated field and the thing that I keep pushing people to do is to specify what it is they're concerned about and justify it. And I think that's what we don't get enough of in our US discourse is specifically what are we competing over? The Trump administration's action plan, there is a vision there that's basically capture the value, capture the economic value of this moment and the national security advantage if it's there. There's just not enough for some people of the avoiding the downsides, many of which had been identified in the Biden administration, both in terms of what the AI safety community talks about and what used to be called the AI ethics community worried about bias and discrimination and all kinds of other harms that mount on less advantaged peoples as these systems are adopted.

Justin Hendrix:

The Trump AI Action Plan also has considerations around ideology, and it claims of course that it's protecting free speech, that it is trying to preserve some form of ideological neutrality in artificial intelligence systems. We've had a few pieces on Tech Policy Press which have kind of countered whether that's even possible, whether it's even desirable on some level, but I don't know. How does that kind of contrast with what you're seeing or hearing on the Chinese side of things?

Graham Webster:

That was just such a funny thing to read and it's gallows humor. As an American, I'm really unhappy to see the government talking about how you need to speak in an "objective way" while in the same sentence or in the same kind of page saying that any mention of DEI is illegal. But it's really a hell of an echo for somebody who's spent years translating Chinese tech law and regulation because at the beginning of pretty much any of these laws and many of the sort of implementing regulations, you'll have this sort of laundry list of stuff that it'll say, "Okay, this law is designed to implement this basic principle or this regulation is designed to implement this law." And by the way, if you're a operator of an information service, you shouldn't violate the social public good or there's all this sort of completely vague, could mean anything language that effectively boils down to if we say so your content is illegal. And that's what the Americans are saying now. It's what's objective truth.

We know for instance, that if you ask one of these chatbots that are available on the market today about your own biography, they're likely to deliver to you some false information about yourself, let alone things that you're researching that you can't fact check with your own memory. It's just funny to me that the free speech people are turning around and saying that you must adhere to certain unspecified principles of "correct" speech. It's obviously an oxymoron, it's contrary to freedom of speech and expression in a way that every time you translate it in the Chinese thing, you're like, yeah, this makes sense. It's an authoritarian single party state and they have pervasive censorship and that's the backdrop. There's a lot of good stuff that goes on in China and a lot of people use irony to get around things and there are violations of the censorship and all of that. But anyway, the rule is political censorship. Reading it in the US it's also political censorship, it's just the context. It should be, we'll see how the courts do. It should be obviously illegal, but I'm not a lawyer.

Justin Hendrix:

Putting aside the kind of censorship concerns and the clear differences in at least the realities of our political systems at the moment, the clear policy direction in the US is dollars and dominance. That's where we're headed under this AI action plan, under this administration. Does the Chinese plan preserve a little more of the kind of concern around safety or is this all six in one half, a dozen the other?

Graham Webster:

I think that's a hard question because one of the things that I heard from a few people in China, and it's actually, and then I saw it in the US action plan, is the idea that, all right, the supposedly most advanced Chinese models, meaning most advanced on the metrics that are currently preferred to decide what's advanced, which is a whole separate conversation. The Chinese ones are a bit behind the most advanced US ones. And so I heard multiple people say, "Look, on a lot of this safety stuff, we expect the canary in the coal mine to be with the US models, however many quanta ahead of the supposed ..." This all assumes a unilinear ascent of there's one path, which I think is insane also. But there's that kind of mentality, like the Americans are going to run into the dangers first because they're further out there.

Justin Hendrix:

Well, that's fascinating. So almost there's a benefit to being the challenger, to being second in that regard?

Graham Webster:

I think there's all kinds of benefits to China's positionality if it doesn't turn out that there's a critical winner takes all moment because for one thing, they're banned from buying the most expensive chips, so they're not. And so you have this race to invest in hyper scale, whatever the biggest, most expensive supercomputers ever in the world. And you've got OpenAI trying to do one and Anthropic and Google and everybody's trying to do it at the same time. There's just a hell of a lot of capital that's being expended in this way, and China's spending a lot of capital too between public sector and private sector. They just can't compete at that scale. So they're capitalizing a bunch of other stuff. And if it turns out that scale of compute doesn't get you the ultimate victory, then the Chinese investments may turn out to be more actually productive on average. So there's all kinds of advantages.

For people who are concerned about, I think of the AI safety catastrophic risk discourse in two parts. There's this sort of imaginary stuff, like Bostrom talking about a superintelligence breaking out and taking over the world and killing us all because it doesn't care for us. That's fun sci-fi stuff, which I don't think needs to be taken very seriously in part because by nature of it, these sorts of events are not very predictable. Then there's the more concrete ones. It does look like within however long people will probably be able to figure out how to mess with new sequences of DNA and fabricating DNA sequences is not that hard compared to how hard it used to be. And so if you're a bad actor with a moderate amount of skill and resources, you might be able to do stuff, or if it's cyber offense, I think that's an area that's just going to be growing and growing and it's a lot of AI systems that intensify existing scary risks.

In that field, I think that there's ... I don't know. My hunch is that there's actually a reasonable amount of attention to this, in both the Chinese and the US context. But neither seemed to really have a solution to one big question, which is at what point should systems stop being open source? And that's a background condition that I think the US plan doesn't really figure out, and the Chinese one doesn't seem to have an answer to at this point. They both seem more interested in getting their firms out there with the open models that would get people to use the suite of services that are built around those models and capture some of the economic benefit.

Justin Hendrix:

Graham, I appreciate very much you joining me and helping me and my listeners understand a little bit better what's going on in China, how to think about it in the context of this race as it were, and I hope we can have you back on again in the future to maybe dig more into some of those unanswered questions.

Graham Webster:

Thank you, Justin. This has been a lot of fun and congratulations on such an awesome podcast and publication that you've been building over these last few years.

Authors