US States Struggle to Define “Deepfakes” and Related Terms as Technically Complex Legislation Proliferates

Kaylee Williams / Sep 12, 2024In the absence of federal guidance with regard to the prohibition of nonconsensual, AI-generated intimate images (colloquially known as “deepfake pornography”), many US state lawmakers are taking matters into their own hands by enacting a variety of laws designed to tackle the mounting issue, which disproportionately harms women and girls.

According to the consumer advocacy organization Public Citizen, which launched a new legislation tracker last week, 21 states have now enacted at least one law which either criminalizes or establishes a civil right of action against the dissemination of “intimate deepfakes” depicting adults (as opposed to minors) who did not consent to the content’s creation.

And while the majority of these laws share the same overall objectives, there are notable differences in the ways that they go about tackling this relatively new, technically complex phenomenon.

For example, some state legislatures have opted to amend existing criminal codes pertaining to sexual exploitation or the nonconsensual distribution of intimate images (NDII) to include “modernized” terminology about deepfakes (see NY S01042), while others have proposed entirely new laws which establish nonconsensual AI-generated content as a form of fraud (NH HB 1432) or an invasion of privacy (CA AB 602).

The texts of these disparate bills also reveal that many states have adopted varying — and in some cases, conflicting — legal definitions for some of the fundamental terms and concepts contained therein, including “deepfakes,” “artificial intelligence,” and “synthetic media.” While decisions around terminology choice and legal definitions may seem wonkish or inconsequential to some, they play a key role in the establishment and protection of victims’ rights.

Furthermore, inconsistencies across states with regard to these terms can lead to unpredictable and adverse outcomes for those who do seek legal redress under these newly-enacted laws, many of which have yet to be thoroughly tested in court. With that in mind, let’s dig into some of the key terms we see defined across the existing AI-generated intimate image bills:

The challenge of defining “deepfakes”

The term “deepfake” traces back to a now-deleted Reddit community of machine learning enthusiasts, who in 2017 collaborated to create “face swapping” software that they used to digitally insert nonconsenting women into pornographic scenes, according to Vice reporter Samantha Cole. Despite its nefarious origins, many states have opted to include the word in their related legislation, with varying degrees of technical specificity.

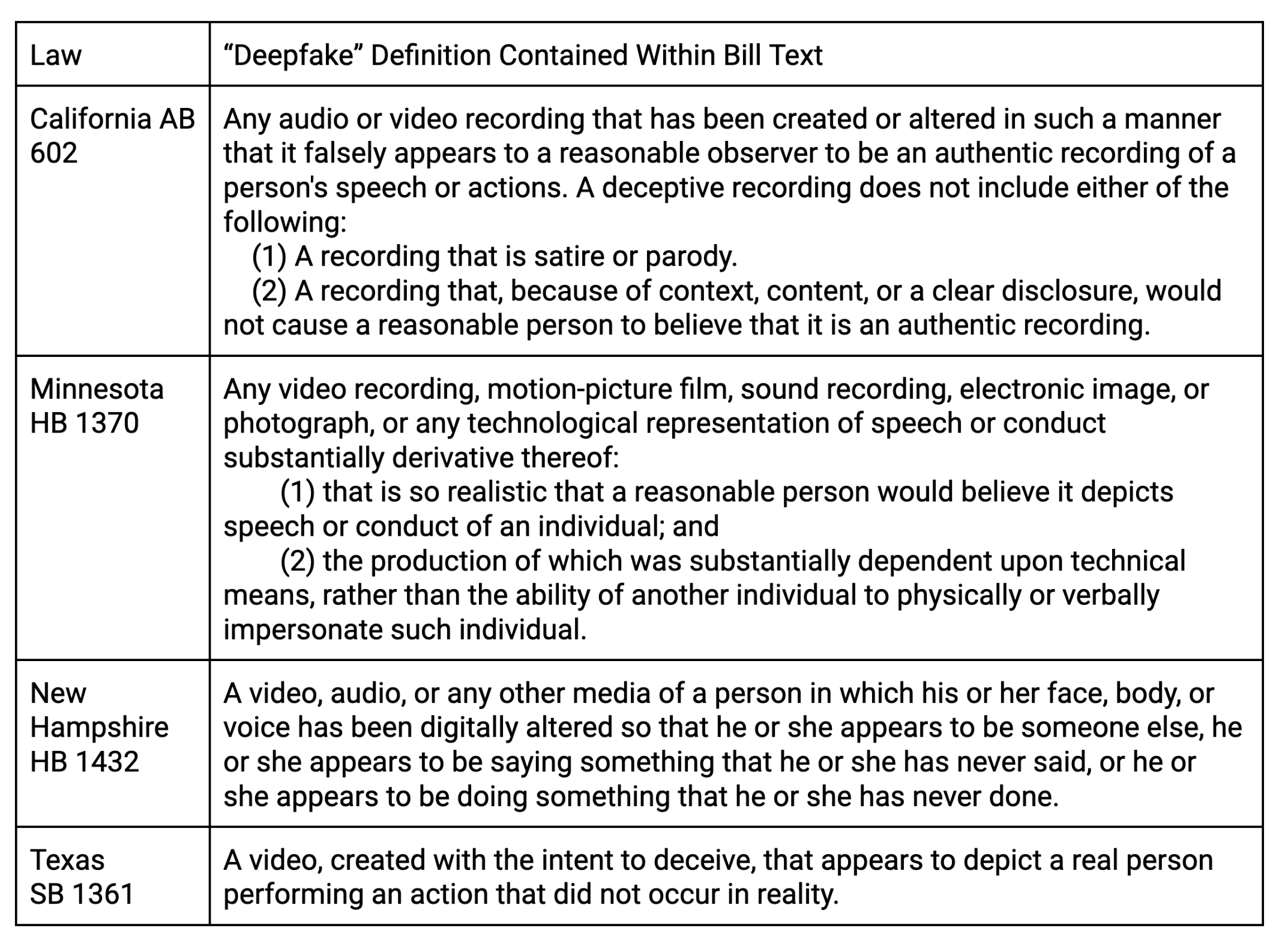

The Texas law (SB 1361), for example, reflects early common conceptions of the word, by defining a deepfake as “a video, created with the intent to deceive, that appears to depict a real person performing an action that did not occur in reality.”

In the years since the popularization of “face swap” or “nudifying” image editing apps, however, “deepfake” has expanded to include manipulated (or, as some might say, “photoshopped”) still images, and even fabricated audio clips. Minnesota’s law (HB 1370) reflects this shift, by defining deepfake as “any video recording, motion-picture film, sound recording, electronic image, or photograph, or any technological representation of speech or conduct substantially derivative thereof.”

Both California and Minnesota have specified that a deepfake must be so “realistic” that a “reasonable” person might be fooled into believing it was authentic in order for its creator to be held liable or charged with a crime. This is a key requirement, in that it will likely prevent obvious Seinfeld parodies and holiday ecards from becoming grounds for lawsuits, but could also complicate matters for victims of abuse whose images are used to create explicit content that is either technically crude or clearly labeled as fake, and therefore might not be considered “realistic” by the court.

Here are a few examples of the full definitions given for “deepfake” in various enacted state laws:

Moving beyond “deepfakes”

In response to the growing ubiquity of the word “deepfake,” advocacy groups such as the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative (CCRI) have advised policy makers against using the term, given its complicated history.

“Wherever possible, we try to avoid using terminology created by perpetrators of abuse and instead seek to use terms that accurately convey the nature and the harm of the abuse,” wrote CCRI Director Dr. Mary Anne Franks in a publication for the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

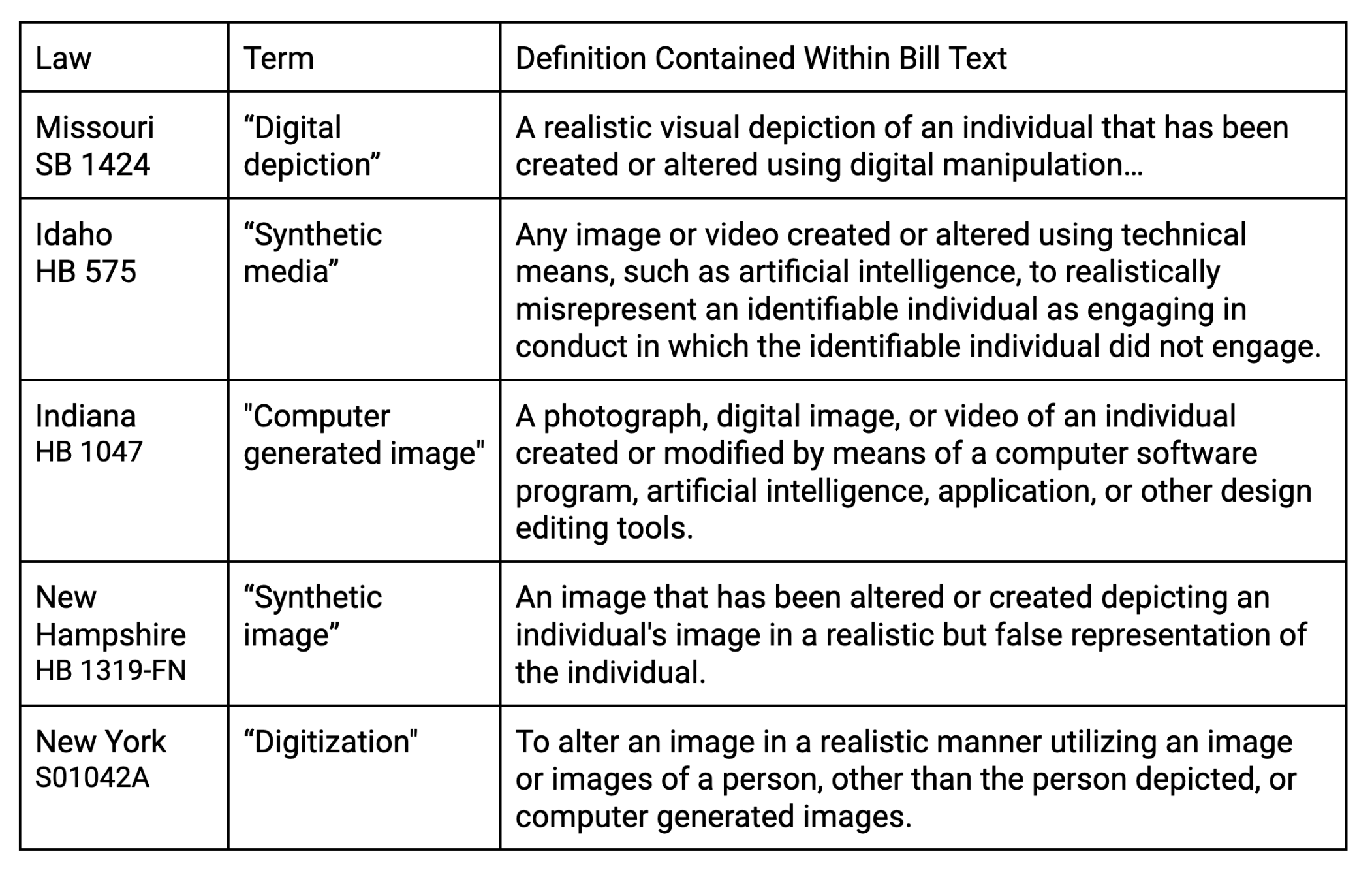

Some states have attempted to heed this advice by employing broader terms such as “synthetic media,” which has become somewhat of an umbrella phrase intended to capture all content (videos, images, etc.) generated or manipulated by machines.

More traditional (and less buzzword-y) deepfake synonyms include “digital depiction” and “computer generated image.”

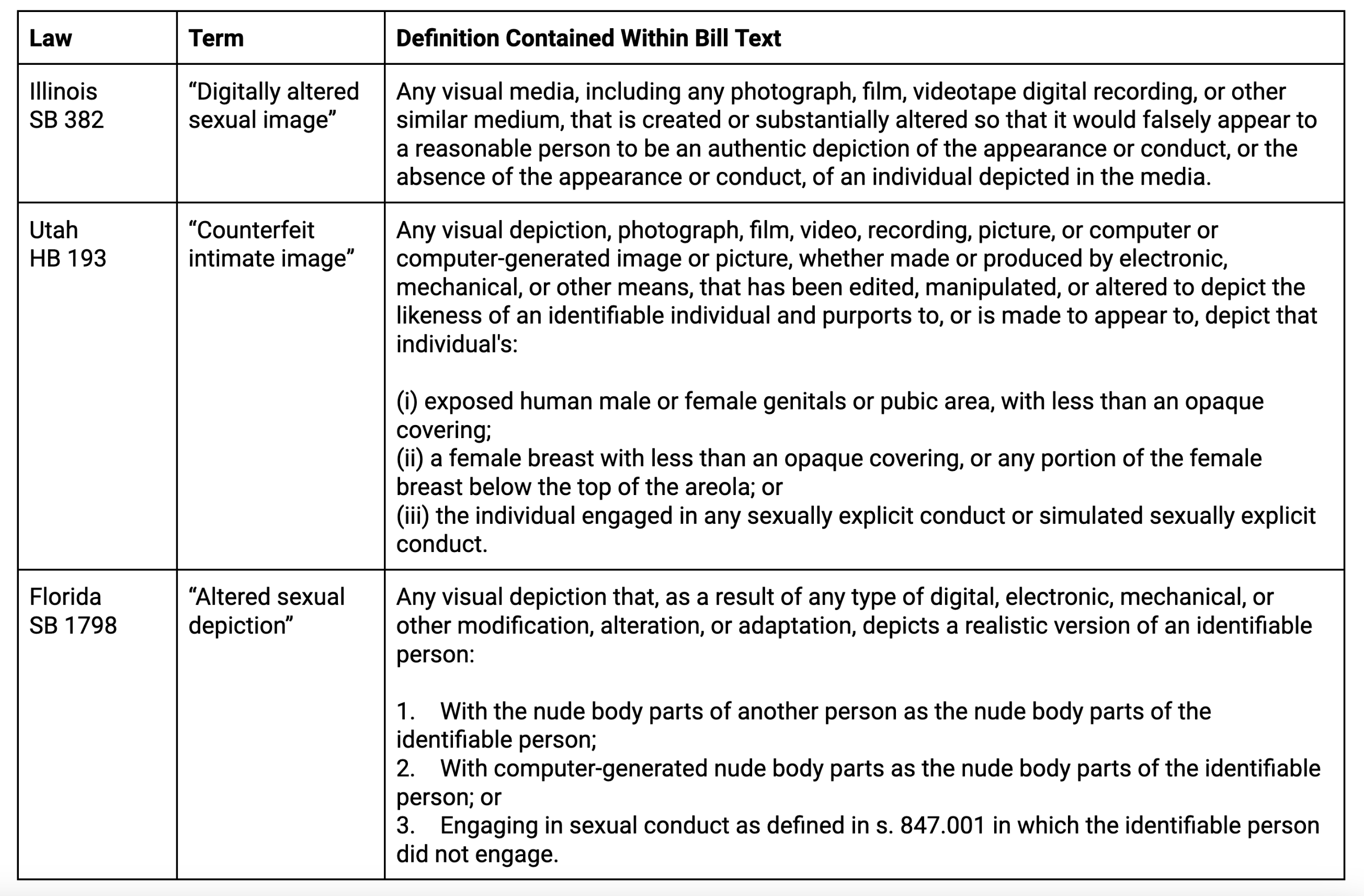

Still other states have chosen to label the abusive content in a way that is specific to sexually explicit depictions, presumably in an effort to avoid stifling AI-generated creations of a more family friendly variety. Terms within this category include “digitally altered sexual image” and “counterfeit intimate image,” the definitions for which appear below:

At this time, it remains unclear whether the use of terms other than “deepfake” will present any specific legal advantages for prosecutors trying cases related to these newly-established crimes, besides the successful avoidance of a term which was coined by some of the phenomenon’s earliest known offenders.

Notably, CCRI’s recommended phrase, “sexually explicit digital forgeries,” does not currently appear in any relevant state-level laws, although it has been incorporated into some federal bills, including the Disrupt Explicit Forged Images And Non-Consensual Edits (DEFIANCE) Act.

What is “artificial intelligence,” again?

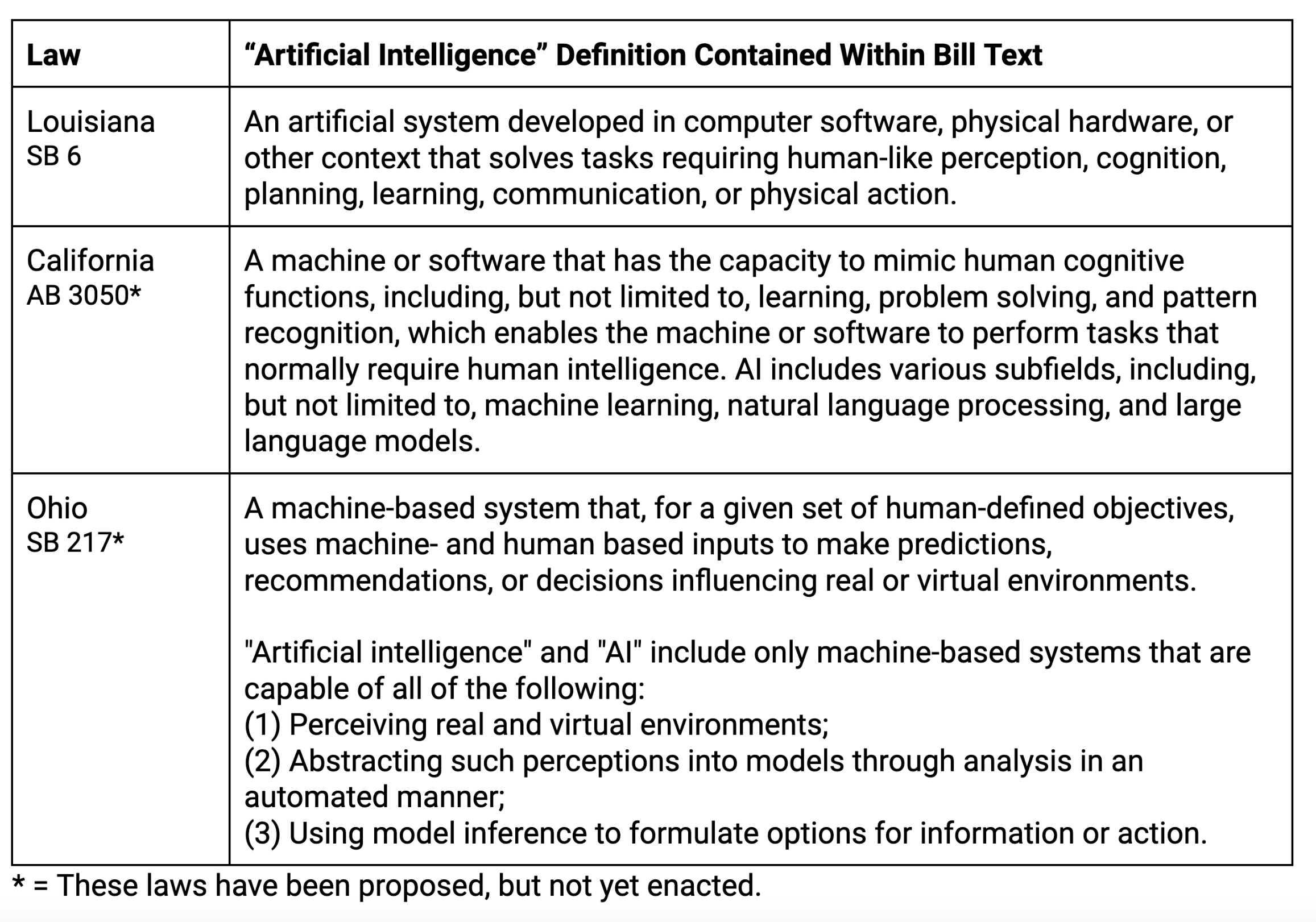

As can be seen in the charts above, several of the newly-enacted laws mention the use of “artificial intelligence” as a tool or a means of creating the abusive content in question. However, close analysis reveals that very few of them present actual definitions of this fashionable phrase. This is likely due to a few reasons.

First, AI is famously difficult to define. Department of State Foreign Affairs Officer and machine learning PhD Matt O’Shaughnessy wrote in 2022 that even “Subtle differences in definition — as well as the overlapping and loaded terminology different actors use to describe similar techniques—can have major impacts on some of the most important problems facing policymakers.” Dr. O’Shaughnessy argued this is because the term is often over-employed, both by relatively non-technical researchers, as well as by marketers who hope to give even simple statistical models an aura of sci-fi mystique. And the trend of labeling any and every software product as “AI-powered” has only worsened in the years since the public launch of OpenAI's ChatGPT and other popular large language models.

Additionally, legal scholars have posited that adherence to too-specific or overly-technical legal definitions for complex concepts (such as AI) can be risky, given the rapidly-advancing nature of the technology. In other words, if policymakers aren’t careful, they run the risk of enshrining definitions into law which will become obsolete in a matter of months, if not weeks.

There are, however, a smattering of states which have opted to provide “AI” definitions in spite of these risks. Here are a few examples:

The “intent to harm” clause

The most significant non-definitional discrepancy between these state laws, however, is the differing approaches to “malicious intent,” a legal concept referring to perpetrator’s presumed intentions at the time of disclosing the abusive content.

While Washington (HB 1999), Iowa (HF 2440) and a minority of other states have criminalized the publication of deepfake intimate images in every instance, the law in Georgia (SB 337) only applies “when the transmission or post is harassment or causes financial loss to the depicted person, and serves no legitimate purpose to the depicted person…” Similarly, Hawaii (SB 309) only penalizes explicit AI content disclosed “with intent to harm substantially the depicted person with respect to that person's health, safety, business, calling, career, education, financial condition, reputation, or personal relationships or as an act of revenge or retribution…”

While these clauses are intended to limit restrictions on the basis of freedom of speech, survivor advocates and legal experts have warned that they could create a loophole which perpetrators might exploit by claiming that they had no desire to harass or harm the person whose image they co-opted for explicit content. News reporting — particularly out of South Korea, where policy makers are facing a “crisis” of AI-content targeting popular music artists — demonstrates that many deepfake creators do think this way, and often contend that they generate intimate images of women (especially celebrities) who they admire or are attracted to, rather than those they wish to harass online.

The problem with inconsistency

While state-level legal protections against AI-generated intimate images are undoubtedly preferable to no protection at all, the fact that these terms and others are named and defined so differently between states is likely to result in 1) widespread confusion among victims, and 2) significant disparities in the ways that the laws are employed and enforced on the ground.

A similar problem already exists with regard to nonconsensual pornography (colloquially known as “revenge porn”), which is banned in 49 states and DC, but still not regulated federally. For over a decade, legal scholars have been arguing that the wide variations in legal severity across state lines have resulted in an unequal system in which victims in some states enjoy more protections from abuse than those in others. Furthermore, this “confusing patchwork” of laws has prevented states from requiring platforms which circulate abusive content globally to comply with local law enforcement efforts. In other words — and as any others have pointed out — the internet is not limited by state lines.

Without federal legislation, deepfake laws appear on track to meet a similar fate. As things currently stand, despite the fact that both states now have deepfake pornography laws on the books, a young woman whose Instagram profile photo has been used to generate an explicit image would likely have legal recourse in California, but not Texas. If the resulting image isn’t considered “realistic,” it may be deemed criminal in Indiana, but not in Idaho or New Hampshire. If the person who generated the image convincingly claims to have done so out of affection, rather than malice, the victim could seek justice in Florida, but not Virginia.

The hypotheticals go on and on, but all of this suggests that intimate deepfakes may only be the latest iteration of the unceasing dehumanization of women and girls in the digital sphere; a rampant problem that Congress has thus far refused to meaningly address.

Authors