Why Africa Is Sounding the Alarm on Platforms' Shift in Content Moderation

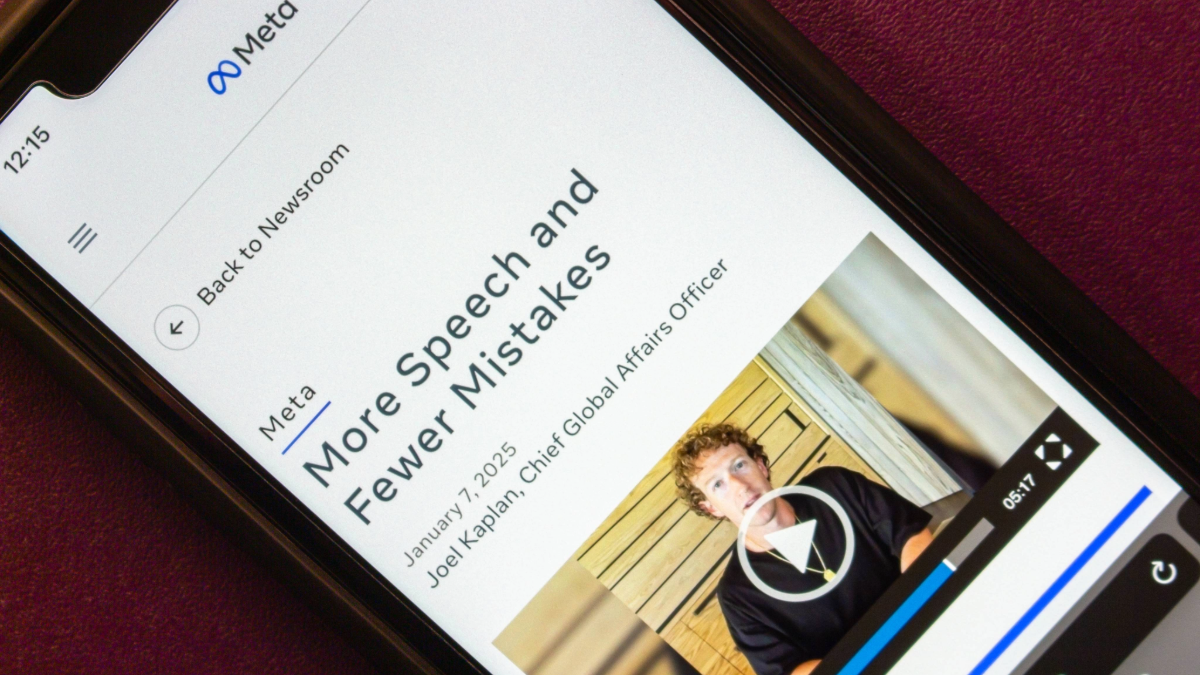

Yohannes Eneyew Ayalew / May 13, 2025On March 11, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Commission), an organ of the African Union (AU), adopted a landmark Resolution 630/2025, expressing concern over recent regressions in content moderation and reduction of fact-checking services by social media platforms—developments that undermine information integrity and the protection of free expression and access to information in Africa and beyond. This resolution emerged after major social media platforms such as Meta and YouTube recently announced a ‘Community Notes’ system to tackle disinformation, which, in turn, is cutting back on professional fact-checking services on their platforms.

This blog post first scrutinizes social media platforms' latest rollback in ending professional fact-checking services and replacing them with the Community Notes system. It then explores whether and how such a move may undermine their due diligence obligations under African and international human rights law.

Community Notes: a replacement for or retreat from fact-checking services?

Technically, Community Notes are a form of crowdsourced content moderation, where users write brief assessments of potentially misleading or inaccurate tweets, posts, or videos (see definitions on X, Meta, and YouTube). While Community Notes are praised for encouraging user participation in content moderation and fact-checking, thereby reducing disinformation, critics show that the system is ill-equipped to address harmful, hate-driven narratives often rooted in disinformation. Not to mention that Community Notes could face the daunting challenge of seeking consensus across divergent perspectives in an increasingly polarised information ecosystem, which could be even more pronounced in conflict-affected regions in Africa and beyond. Moreover, Jude and Matamoros-Fernández reveal that replacing professional fact-checking with the Community Notes model is reductionist, as it targets a narrow view of disinformation—focusing solely on falsity rather than its historical, social, cultural, economic, and political dimensions. Furthermore, one of the major risks of Community Notes is its vulnerability to user manipulation. On X, for instance, there is little to prevent users from coordinating their voting behaviour to game the ranking system—often using multiple accounts (see e.g. Bovermann). These risks are further amplified in the African context, where state-sponsored disinformation networks and entrenched structural inequalities persist.

The key normative statement of the African Commission is that Community Notes, on their own, are neither an alternative to corporate social responsibility nor a substitute for independent fact-checking. The Commission underscores that (preambular 6):

[C]ommunity Notes mechanisms are not an alternative to the companies own responsibilities to uphold their corporate responsibilities and ‘community standards,’ and declaring further that ‘community notes; are also not a substitute for independent fact-checking and registering our concerns that ‘community notes’ are susceptible to be captured by forces that do not respect human rights.

Why is effective content moderation and fact-checking needed in Africa?

In fact, many practical instances in Africa have seen social media platforms criticized for their inadequate content moderation efforts. These platforms have been particularly ineffective, for example, in protecting users from external interference during election periods in countries like Kenya and Nigeria, and have also struggled to effectively regulate hate speech and deepfakes in Ethiopia and Sudan, which has contributed to inciting violent ethnic strife and armed conflicts.

That said, several reasons motivated the African Commission to adopt this timely resolution and clarify its position on one of the pressing issues of our time. Primarily, the Commission recognizes that information disorder—whether through disinformation, AI-generated deep-fakes, shallow-fakes or propaganda—implicates not only the rights to non-discrimination and freedom of expression, as outlined in Articles 2 and 9 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, respectively, but also a broader set of digital human rights (see preambular 2-3). The recent announcement by major social media platforms of rolling back the established practice of professional fact-checking in favor of the Community Notes system is a key reason for the African Commission to raise a deep concern. It cautions that this step backward by Big Tech companies could seriously impact human rights in the digital environment (see preambular 4).

The other reason is linked to the prevalence of linguistic blind spots in content moderation, arising from the lack of coverage of African languages in platform governance and the inadequacy of large language models (LLMs) in handling African languages (see preambular 5). In a paper on the international human rights-based approach to content moderation, I argue that platform content governance, even when supported by automated tools and large language models (LLMs), still falls short of addressing the interests of users in the Global South, particularly Africa—let alone discontinuing independent fact-checking altogether. The African Commission is also deeply concerned about the weaponization of platforms and their related AI services, which, instead of remaining neutral, risk advancing political agendas—including foreign interference in elections across Africa (see preambular 7). In fact, African elections have served as a testing ground for foreign interference, as demonstrated by the Cambridge Analytica scandal. In a continent where the digital divide remains stark and is compounded by poor media literacy, where content moderation has repeatedly failed and many democracies remain fragile, scrapping independent fact-checking in favor of a crowdsourced Community Notes system is tantamount to putting a bandage on a bullet wound. At best, the Community Notes system is poised to fail—and at worst, it may be dead on arrival—when it comes to achieving its intended goals within Africa’s current information ecosystem.

Skirting around due diligence duty?

The decision to scrap fact-checking and loosen content moderation services means platforms are skirting their responsibilities to respect and protect human rights under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). In this regard, the African Commission reiterates that (see preambular 8):

(…) digital companies that provide services in Africa to adopt transparent human rights impact assessments as part of due diligence for any changes being contemplated, or for any upcoming risk situations in line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, applying these assessments especially in cases of elections, health crises and the possibility of violent conflict.

This suggests that while platforms are required to moderate contents as part of an ongoing duty of due diligence for any changes being contemplated to prevent or mitigate harms or foreseeable risks arising from their operations as per Pillar 2 Principle 17 of the UNGPs, they are not living up to expectations when it comes to content moderation and fact-checking in the context of armed conflicts. For example, in several cases involving African countries such as Alleged Crimes in Raya Kobo (2021) and the Tigray Communications Affairs Bureau (2022), the Oversight Board recommended that Meta conduct a due diligence assessment on how its platforms, including Facebook and Instagram, have been used to spread hate speech and unverified rumours that heighten the risk of violence in Ethiopia. However, the company has notadequatelyheeded these recommendations to date. In fact, Meta was supposed to complete the due diligence assessment within six months (i.e., by July 13, 2022) from the moment it responded to the Board’s recommendations, which was on January 13, 2022. Nevertheless, according to its update on June 12, 2023, Meta has not yet published its full due diligence assessment report on Ethiopia, perhaps hinting at its non-compliance with the Board’s decision.

Conclusion

The adoption of Resolution 630/2025 by the African Commission represents a much-needed clarification and stance on the recent regression in content moderation services by major social media platforms, which could potentially impinge on several human rights in Africa and beyond.

One of the key recommendations of the African Commission in this resolution is a call to action for the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa to develop guidelines—through a multistakeholder approach involving civil society, regulatory bodies, and technology companies. These guidelines help guide States to effectively monitor platform performance and support efforts to strengthen information integrity online, including the role of independent fact-checking in the African context. While the call to develop guidelines is a step in the right direction, it cannot be the end of the road. Lessons from Europe show that the European Commission not only has clear normative rules, but is also beginning to crack the whip on very large online platforms (VLOPs) through enforcement actions under Article 73 of the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Code of Practice on Disinformation.

As such, the African Commission should go further, including launching investigations into major platforms that are shirking their due diligence obligations under African and international human rights law, as mandated by Article 45 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

Authors