Why Global Majority Leadership Matters for Tech and Migration Policy Today

Petra Molnar / Feb 19, 2026Petra Molnar is a fellow at Tech Policy Press.

Refugees and people-on-the-move create the first-ever Manifesto on border technologies in Nairobi, Kenya, November 2025

In April 1955, representatives from twenty-nine Asian and African countries gathered in Bandung, Indonesia, for what would become one of the most consequential political meetings of the twentieth century. The Asia-Africa Conference brought together states and movements emerging from colonial rule to articulate a shared vision of self-determination, non-alignment, and resistance to imperial domination. Bandung was not merely a diplomatic event. It was a declaration that knowledge, leadership, and political imagination did not belong exclusively to Europe and North America. It insisted that those most affected by global power asymmetries must be central in shaping the world to come.

Seventy years later, that lesson feels urgently relevant again.

Today’s geopolitical terrain is marked not only by renewed authoritarianism and militarization but also by the rapid expansion of surveillance technologies, artificial intelligence, and data-driven governance. Nowhere is this more visible, or more consequential, than in the domain of migration. Borders have become testing grounds for high-risk technologies: biometric databases, predictive analytics, drones, social media monitoring, and spyware are increasingly deployed to sort, track, deter, and criminalize people on the move. These systems are often developed and exported by powerful states and private companies, then implemented in contexts such as the border or in places of occupation like the West Bank or Gaza, where legal protections are weakest and accountability is hardest to secure.

Against this backdrop, the Migration and Technology Monitor (MTM) convened a mini-Bandung conference, a first in-person Gathering in Nairobi in November 2025. Like Bandung, Nairobi was chosen deliberately. It was a Global Majority space in which people most affected by surveillance and border technologies came together not as subjects of research or policy experimentation, but as knowledge-producers, political actors, and experts in their own right.

The gathering brought together MTM Fellows, all with lived experiences of migration and occupation, and partners from across Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Many traveled on precarious visas; some were unable to attend at the last minute due to restrictive migration regimes, a stark reminder of the very systems under discussion. Over three days, participants shared research, reflected on their lived experience, and collectively articulated principles for how technology should and should not govern human movement. The outcome was not just a meeting and a report, but the foundation of the MTM Manifesto: a living document grounded in care, accountability, and resistance to technological harm.

Participatory methodologies as policy intervention

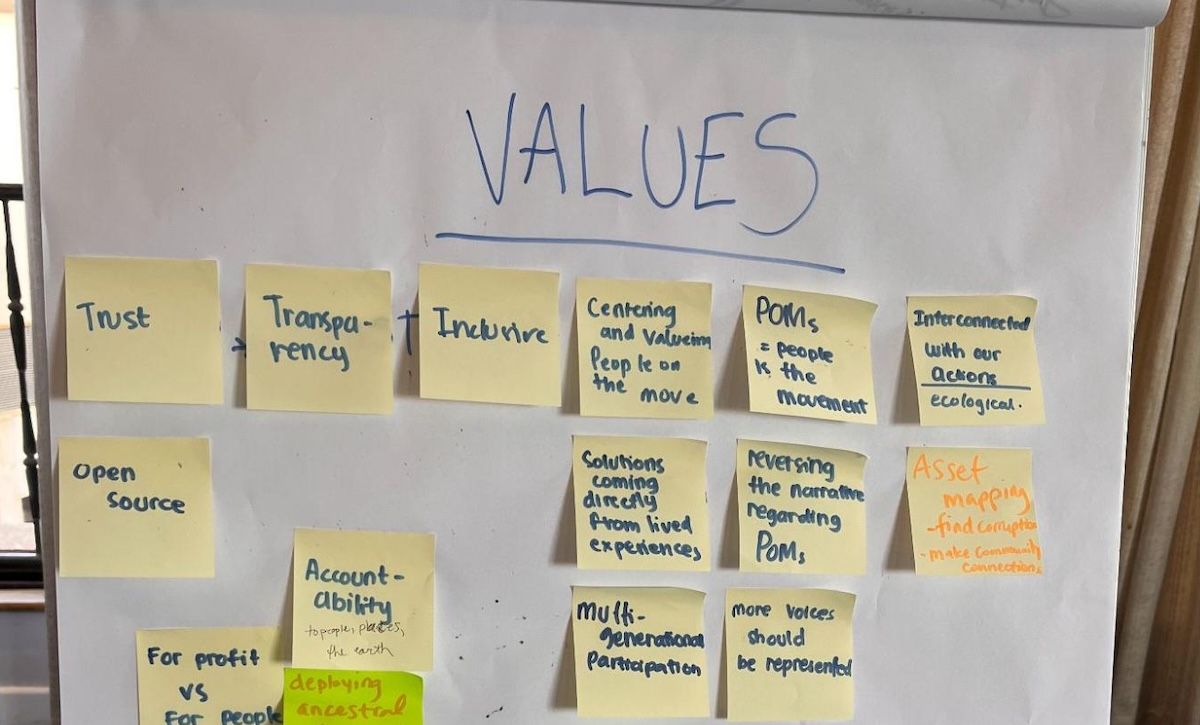

The work of the Migration and Technology Monitor is anchored in participatory methodologies, not as a buzzword or consultation exercise, but as a political and ethical commitment.

Participatory methodologies have emerged globally as a response to centuries of extractive research practices in which communities, especially those marginalized by race, class, gender, and migration status or occupation, were treated as objects of study rather than as knowledge producers. Across Majority World social movements in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, participatory approaches are not simply techniques but also political commitments to shift power differentials. They challenge top-down, western-centric models of expertise by insisting that people closest to social and technological harms must drive the questions, methods, and solutions.

A touchstone for this work is the long tradition of Indigenous, disability rights, and community- organized knowledge production, grounded in collective decision-making, horizontal structures of authority, and the refusal to replicate colonial patterns of knowledge extraction. These methodologies begin not with academic or funder agendas but rather with the lived realities and political goals of communities themselves, exemplified in the powerful rallying cry “nothing about us without us. ” This principle demands that no policy, technology, or research concerning a community should be designed without the community’s meaningful participation and leadership. Globally, participatory methodologies also explicitly decenter Western epistemologies, which often privilege technical expertise and elite institutions over lived experience.

New report by the Migration and Technology Monitor, Feb 2025.

Decolonial thinkers from Linda Tuhiwai Smith to Boaventura de Sousa Santos argue that true participation requires dismantling the hierarchy that treats Majority World knowledge as anecdotal or peripheral. Instead, our participatory frameworks at the MTM recognize that communities living through surveillance, displacement, and technologically driven harms and violence hold forms of expertise that cannot be replicated from the outside. Expertise grounded in lived experience understands system failures intimately, knows which interventions are harmful or helpful, and can articulate needs that conventional research overlooks. Participation is therefore not a checkbox or a tokenization metric to be checked off. It is a daily practice of redistributing power, authorship, and decision-making. It requires co-design of research tools, shared ownership of data, and accountability structures that answer to impacted communities rather than funders or institutions.

Done well, these approaches produce knowledge that is more accurate to the lived reality of communities at the grassroots level, more grounded in liberation ethics, and more capable of generating real-world solutions. In an era when technologies of migration control are rapidly expanding, often without oversight and accountability, participatory methodologies offer a radically different approach: one where affected people determine the terms of research, resist technological harms, and imagine alternative futures grounded in autonomy, dignity, and collective liberation.

Participatory approaches matter deeply for policy. When affected communities are excluded from policy discussions, powerful actors like states and the private sector push out technologies that are misdesigned, misused, and harmful. Yet, when lived expertise is centered, research becomes more accurate, governance more legitimate, and interventions more effective. Participatory methodologies are not only ethically necessary, but they are also a proactive and corrective approach to policy failure. We have already seen this failure all around the world, from the EU’s AI Act falling short on rights protections at the border to the US actively weaponizing technologies to detain, harm, and kill people on the move and their allies.

Nairobi as a counter-model to extractive tech governance

The Nairobi Gathering stood in sharp contrast to dominant global tech policy spaces, where conversations about AI, surveillance, and border control are often led by governments, multilateral institutions, and private firms, with limited to no representation from those most affected. In many such forums, migration technologies are either discussed in abstract terms, such as efficiency, interoperability, security, or explicitly conflated with military technologies deemed necessary to secure the world’s border, while the human costs remain peripheral.

In Nairobi, the starting point was different. Discussions and sharing circles centered on how technologies operate on the ground: how biometric registration can expose refugees to future harm; how data collected for “humanitarian” purposes can later be repurposed for enforcement; or how digital traces are later weaponized against people seeking safety. However, there was also space for joy and resistance. Participants also shared strategies of resistance: community mapping, encrypted communication, documentation, storytelling, and refusal.

Importantly, the gathering also confronted the role of the private sector. Border technologies are not neutral tools. Instead, they are products of a growing and lucrative multi-billion-dollar border and surveillance industry that profits from racism, exclusion, and border violence. Defense contractors, data brokers, and tech startups increasingly shape migration governance through opaque contracts and proprietary systems, while avoiding accountability and oversight. Any serious policy response must therefore grapple not only with state practices but also with the political economy of border tech.

The MTM manifesto and a policy agenda from the ground up

The MTM Manifesto is both a critique and a roadmap. At the MTM, the principle of participation shapes everything from fellowship design to research outputs. Fellows who are people with lived experience of displacement and occupation. They are not asked to validate pre-set policy agendas. Instead, they define the questions themselves. The Manifesto, written by MTM Fellows and allies who attended the Nairobi Gathering, is both a snapshot as well as an online ‘living sculpture,’ where the MTM invites people with lived experience of migration and occupation to comment, contest, and co-create the next version.

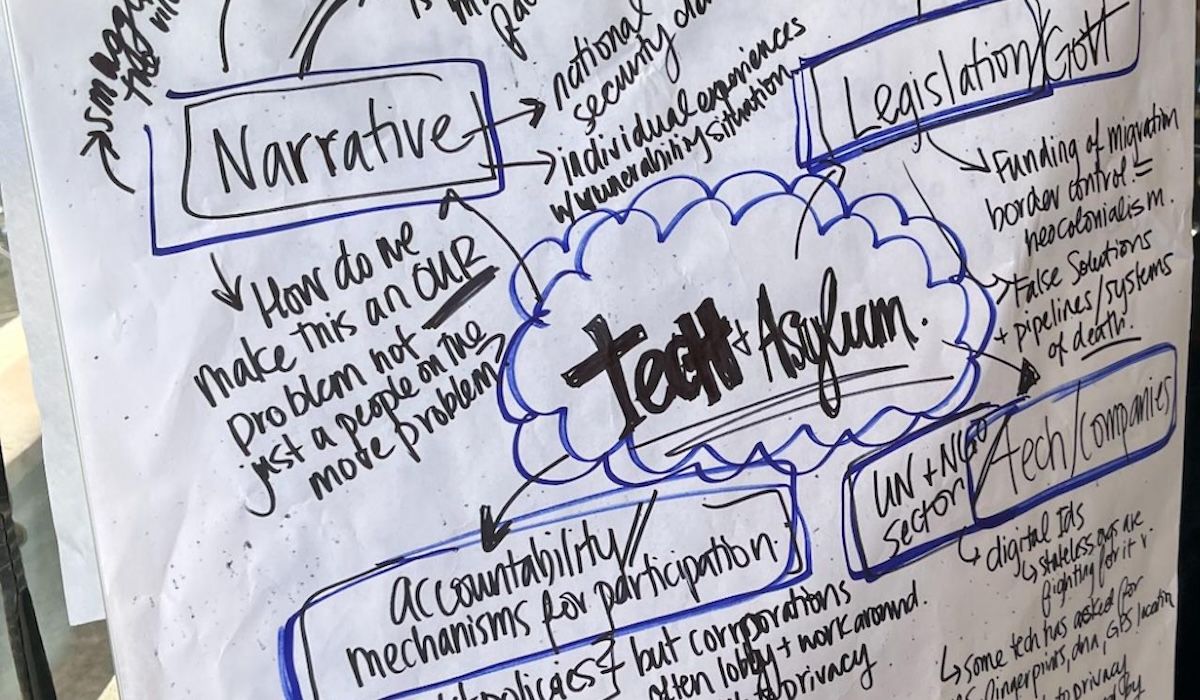

First drafts of the MTM Manifesto, Nairobi, Kenya 2025.

The manifesto articulates 10 principles for technology governance rooted in dignity, consent, accountability, and community leadership. It rejects the normalization of experimentation on marginalized populations and calls for binding safeguards, transparency, and the right to refuse harmful technologies. Its ten demands highlight the universality of migration and human movement and that it is not a crime. The manifesto also calls for a turn away from technological exploitation, instead placing human dignity, transgenerational learning, and the protection of fundamental human rights at the centre of any technological development and deployment.

The Manifesto also reflects real-world issues, such as the need to upskill communities in repair skills to decrease waste culture and encourage social cohesion, pushing for accessibility, and technological development rooted in justice and equity. Privacy remains a central consideration, especially given the very sensitive data collected in spaces of migration, as well as the demand for minimization of algorithmic decision-making in high-risk spaces like borders and refugee camps. Lastly, the MTM Manifesto calls for the centering of lived experience, with solutions coming directly from lived experience.

For policymakers, the implications are clear. First, affected communities must be meaningfully involved in the design, evaluation, and oversight of migration technologies, not as an afterthought, but as a condition of legitimacy. Second, impact assessments must go beyond technical performance to address racialized and geopolitical harms. Third, public institutions must resist over-reliance on private vendors whose incentives are misaligned with human rights. And finally, participatory knowledge production should be recognized as a form of policy expertise in its own right.

Why global majority perspectives matter now

70 years ago, the Bandung conference reminded the world that those historically excluded from power possess not only grievances, but visions for alternative futures. Nairobi reaffirmed that insight in the context of twenty-first-century technological governance and its impacts on people crossing borders. Importantly, this technology does not stay at the border. As surveillance systems proliferate, the lessons learned in migration contexts will increasingly shape broader forms of automated governance in all facets of public life. If policies are built on exclusion at the margins, those logics will travel inward. Conversely, if accountability, care, and participation are established where power is most aggressively exercised, they can set precedents for more just technological futures.

MTM Gathering, Nairobi, Kenya 2025.

At a moment when technology policy is often driven by speed, competition, and profit, the Migration and Technology Monitor offers a different starting point: one grounded in lived experience, collective ethics, and the insistence that people-on-the-move are not problems to be solved, but partners and experts in shaping the rules that govern us all.

Authors