X Polls Skew Political Realities of US Presidential Elections

Przemyslaw Grabowicz / Sep 20, 2024Questionable voting patterns in X polls might contribute to an inaccurate impression of Donald Trump’s electoral performance, writes Przemyslaw Grabowicz, drawing on empirical research.

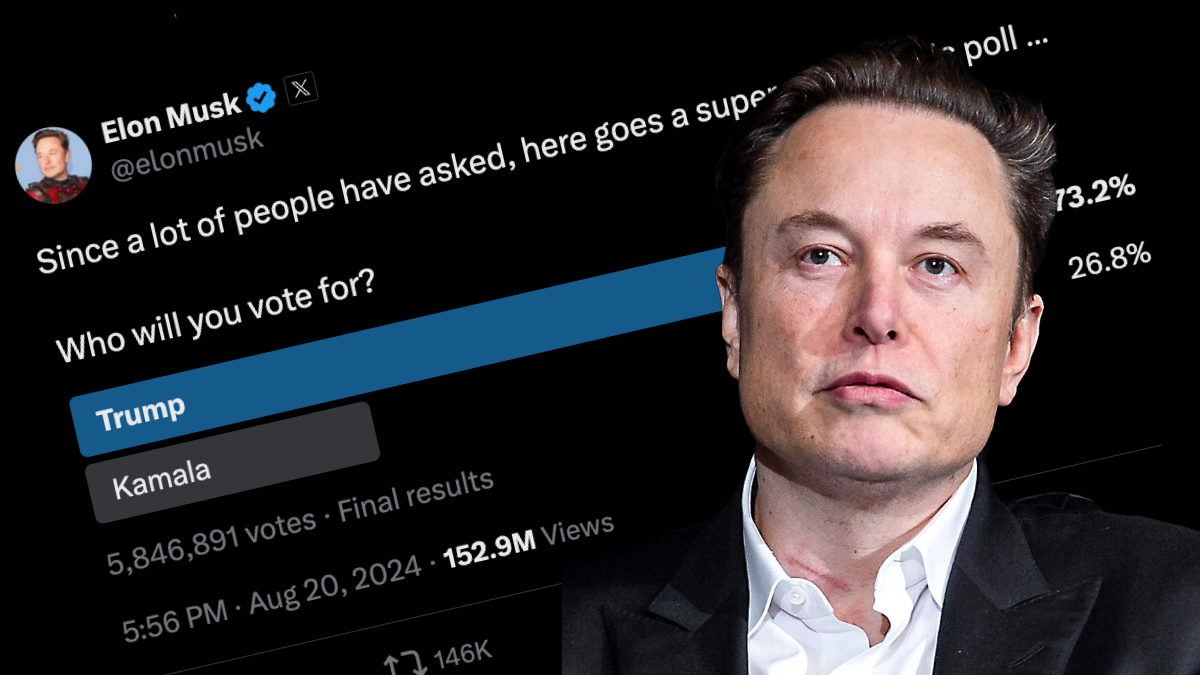

Informal political polls have grown in popularity on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter. For instance, one such poll, conducted recently by billionaire X owner Elon Musk, received over 5 million votes. It showed former President and 2024 Republican nominee Donald Trump leading over Vice President and 2024 Democratic nominee Kamala Harris by a landslide, 73% to 27%. Trump publicly featured the results of multiple such polls on his social media platform, Truth Social, presumably to create the impression of his overwhelming popularity.

However, during both the 2016 and 2020 US presidential elections, such polls were significantly skewed by questionable votes, many of which may have been purchased from troll farms. This conclusion, reached by a team of scientists I led when I was a research assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, shows that X’s poll feature reports biased public vote counts. On average, the results of such informal polls during 2020 favored Trump over Joe Biden, 58% to 42% in a head-to-head comparison. This year, they favor Trump over Harris, a whopping 76% to 24%, according to measurements updated daily at our website, socialpolls.org.

Additionally, our team found that in 2020 there were approximately 50% more questionable votes in pre-election polls than in those following the presidential elections, suggesting that skewing social polls is likely a deliberate tactic to try to influence political outcomes. We use the term “questionable votes” to refer to unexplained votes in polls, which recently were noticed by billionaire investor Mark Cuban. In a post on X, Cuban asked Musk to explain the origin of such questionable votes, but did not appear to receive an answer.

My research lab and I have studied biases and questionable votes in election polls on X for a few years now. The results were published recently in the Journal of Quantitative Description and will be published at the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM) of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI).

Ahead of the 2020 presidential election, there were over 20 million votes cast in more than 100,000 straw polls on X/Twitter. These polls together had Trump winning a landslide victory, when in reality, Biden won the election. We wanted to take a closer look, to see if the polls were legitimate and what they could tell us about how social media influences American politics.

This was no small task. We estimate that there are over 1 million social polls of all kinds published on X/Twitter every month. These social polls could ask anything—do you prefer cats or dogs, jazz or heavy metal?—and so we eventually narrowed the results down to purely political polls asking some version of the question, “Who will you vote for?” or “Who will win the election?,” and which listed both Biden and Trump (or Clinton and Trump for the 2016 election) among the candidate options.

What we found was striking.

Social polls consistently predicted a landslide election win for Trump in both the 2016 and 2020 presidential contests. On average, the 2020 social polls had Trump winning by 58%, though he came in at only 47% in the popular vote.

According to our research, both the 2016 and 2020 social media polls were predominantly crafted by accounts that appeared to be male and who had a pronounced bias for Donald Trump. Compared to traditional exit polling conducted on election day, voters in social polls were more likely to be men. Furthermore, the political ideology of those authoring and responding to social polls skewed right, while those who retweeted and liked social polls were even more likely–by over 10 times–to portray themselves as conservative.

But political identity alone didn’t explain what our research team was seeing. In an international twist, it seemed that Polish politics might.

In 2020, the Polish state media outlet TVP INFO ran a detailed article on the results of a Twitter poll it conducted asking who won a Polish presidential debate. What TVP INFO claimed is that out of 35,202 votes, 19,539, or 44.5%, had been bought from troll farms. We wanted to know if something similar might be happening in the US.

At issue is a discrepancy in how X/Twitter displays poll votes. There is a public number—that anyone who engages with or votes in the poll can see—but there is also a private number, available only to the poll author. In the case of the TVP INFO’s Polish presidential debate poll, the public figure was 19,539 votes greater than the private number—and the public had no way of knowing this.

In other words, there’s no way for the public to tell the difference between a purchased vote and a legitimate one.

To see if something similar was happening in the US, we ran our own polls asking respondents whom they would vote for: “Potoo from Arizona, Walrus from Alaska, or Sheep from New York,” and then purchased votes for these polls from various troll farms.

Once we analyzed all the data, we found that the discrepancies between public and private vote counts closely, though not perfectly, conformed to the number of purchased votes. Somehow, it would appear that X may be taking the purchased votes out of the poll-author’s view, but no one knows how or why. But without seeing X’s source code and data, we cannot confirm that all questionable votes are purchased votes.

We also surveyed 984 authors of 2020 Twitter social polls, asking to see their private vote count. While only a handful responded, the results were consistent across all the studied polls. Strikingly, there appeared to be about 50% more questionable votes before the 2020 presidential election than afterward, suggesting that social poll manipulation is a deliberate tactic to skew voter perception of public opinion.

And finally, some of the questionable pre-election social polls predicting a Trump landslide were used to reinforce voter-fraud beliefs once the actual election results came in. This phenomenon took place again in 2024. For example, Elon Musk’s poll result showing Trump winning 73% to 27% was posted with a comment, “𝕏 debunked the mainstream media's false polls and claims that reported an even contest between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris,” by an X account called DogeDesigner, which Elon Musk often retweets himself. That post was viewed over 7 million times.

According to over a thousand social polls published this year on X, Trump leads in the 2024 race, winning an average 72% of votes in contrast to Harris’s 28%. We developed socialpolls.org to track such polls and correct their apparent biases. After correcting the demographic and partisan biases, socialpolls.org shows a close race, nearing 50% support for each of the presidential candidates.

Our work cautions that social media platforms lack transparency, even for things as important as informal polls on national elections. If it’s happening in that context, then we should be concerned whether it’s happening in many others, as well.

I recently accepted a faculty position at University College Dublin. My move is, in part, motivated by the introduction of the Digital Services Act (DSA) in the European Union, a regulation that facilitates the study of social media platforms and their impact on democratic societies. Without such regulation, it would be practically impossible to continue studying polls on X, because X has limited academic access to data since Musk bought the platform.

Authors