X’s Updated Misgendering and Deadnaming Policy Should Concern All Social Media Users and Believers in Democracy

Belle Torek / Mar 14, 2024The saga of X’s recent updates to its abuse policy should concern LGBTQ+ people, social media users, and all believers in democracy. While the platform’s express refusal to enforce its own misgendering and deadnaming policy, except when required by law, is unlikely to shock the tech policy community, this turn of events has disconcerting implications for online harassment, free expression, and digital democracy. The decision to simply sidestep voluntary moderation efforts altogether could set a dangerous precedent for other platforms’ approaches to abuse and other harms, anti-LGBTQ+ and otherwise.

X reinstated its misgendering and deadnaming policy, but won’t enforce it voluntarily.

A few months after his October 2022 acquisition of Twitter, Elon Musk eliminated the platform’s misgendering and deadnaming policy, which had prohibited users from referring to a transgender or nonbinary person by the name they used before transitioning or from purposefully using the wrong gender for someone as a form of harassment. At the time, Musk offered the explanation that targeted harassment of transgender users was “at most rude,” and that disagreement with another person’s personal pronouns is a free speech issue more than anything else. We at the Human Rights Campaign denounced the move, recognizing that it jeopardized LGBTQ+ users’ free expression and safety while inviting bad actors to target two-spirit, transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive users both on- and offline. When news arose last week of X’s quiet reinstatement of the policy, we expressed skepticism of the revived but altered rule, which was already a shell of what it once had been.

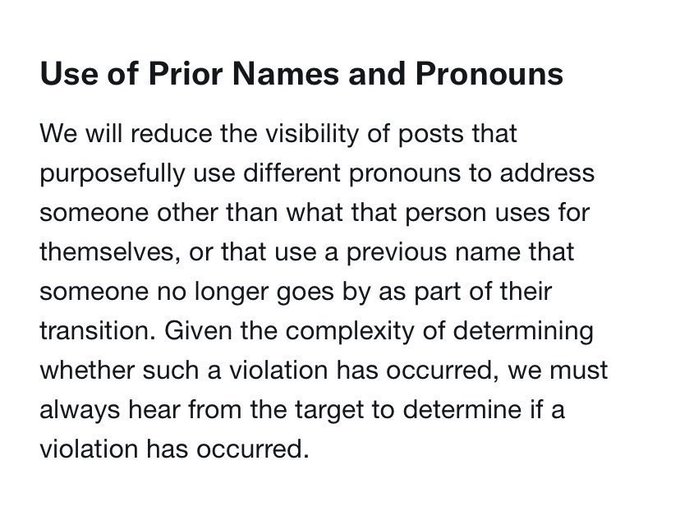

Before Musk’s acquisition of the platform, targeted misgendering and deadnaming were prohibited on Twitter altogether, with enforcement actions ranging from content takedown to account suspension. As of Friday, March 1, though, X’s Use of Prior Names and Pronouns policy only mentioned reduction of the visibility of targeted misgendering and deadnaming – not removal – and only if reported by targeted users themselves, as opposed to allies and witnesses of anti-LGBTQ+ abuse.

A screenshot of X’s misgendering and deadnaming policy as of March 1, before further limiting changes to enforcement reported by March 4.

When prominent far-right users, including Libs of TikTok founder Chaya Raichik, demanded preservation of their X-endowed permission to target transgender users on the platform and deliberately misgendered and deadnamed notable transgender people to stress-test X’s enforcement, Musk reassured them in a series of posts that X would not enforce its policy against their abusive conduct. The shell policy – paired with the hefty burden it places on targets of anti-LGBTQ+ hate, its lackluster enforcement, and its exemptions for high-profile far right users – was a far cry from the steps necessary to prevent the severe harassment and abuse of LGBTQ+ users.

By the next Monday, X’s policy had changed yet again, with the added preamble of five words that confirmed our worst suspicions: “where required by local laws.” Now, only laws – not the good-faith content moderation efforts X users had once relied on – could protect LGBTQ+ users from the kind of abuse that chills community engagement and forces them out of the “de facto public town square” altogether. The catch, of course, is X’s knowledge that these laws overwhelmingly don’t exist.

A commitment to follow the law is no commitment at all. Further, while the First Amendment does not compel platforms to remove hate speech, common decency does.

X’s commitment to act, but only when the law requires that it do so, is an insidious sleight of hand for two reasons. Firstly, any policy that agrees to comply with existing law is naturally performative, since complying with the law is a requirement, not some voluntary feat of valor.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, there are no US laws that require a social media company to limit the spread of targeted misgendering and deadnaming on its platform. In fact, there are almost no laws in any jurisdiction that prohibit this. When far-right users again decried the existence of X’s misgendering and deadnaming policy, even in its current state, Musk again reassured them the policy “should not apply outside of Brazil.”

In another Tech Policy Press piece, Jenni Olson and Leanna Garfield of GLAAD’s Social Media Safety program have correctly called for an understanding of misgendering and deadnaming as a form of hate speech, which social media companies generally prohibit on their platforms, and remove voluntarily. An illustrious body of First Amendment jurisprudence has long protected hate speech in the United States, insofar as it doesn’t rise to the level of a few categories of unprotected speech: for instance, true threats, fighting words, and incitement. The threshold for each of these standards is necessarily high, in order to avoid chilling necessary expressions of dissent. Still, the First Amendment only applies to government actors and does not bar private companies from voluntarily removing hate speech. Moreover, there is also a long body of federal case law, including precedents from the Supreme Court of the United States, finding that speech can be restricted when it amounts to harassment of an individual, as opposed to merely unpopular speech.

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, entitled “Protection for private blocking and screening of offensive material,” broadly shields platforms from liability for content its users post. At the time of Section 230’s 1996 adoption, the applications to today’s social media platforms weren’t necessarily foreseeable. At the same time, Section 230 has always encouraged private actors like social media platforms to make good-faith efforts to remove harmful and offensive content, such as misgendering and deadnaming, without fear of liability. While US law as it exists does not force platforms to take down anti-LGBTQ+ abuse, it clearly empowers them to do so.

In short, X recognizes that it has no legal obligation to take down anti-LGBTQ+ abuse, but what is most concerning is its rejection of any social obligation to do so. Through its updated misgendering and deadnaming policy, X is implicitly capitulating to hateful and extremist ideologies, jeopardizing the safety of LGBTQ+ users, and giving carte-blanche to every bad actor who wants to use X to peddle anti-LGBTQ+ misinformation, hate, and abuse. While X’s disturbing precedent poses the most immediate risk to X’s LGBTQ+ users, it raises the questions of which other forms of abuse X will disregard next, and whether other platforms will follow suit. The answers to some of these questions may become clear in the coming months, as the United States Supreme Court considers the long awaited Moody v. NetChoice and NetChoice v. Paxton, rulings which could set new parameters for platform content moderation.

The Net Voice of NetChoice: the impact of these cases on platforms’ voluntary moderation efforts remains to be seen.

While platforms’ authority to implement and enforce their desired content policies has historically been taken for granted, things have changed over the last couple of years in the wake of Moody and Paxton, which concern Florida and Texas state laws that curtail platforms’ discretion to moderate content that violates their policies. The Supreme Court is at last deliberating whether states’ efforts to impose content moderation restrictions are consistent with the First Amendment, and discerning the degree to which such legislation interferes with Section 230’s Good Samaritan provision. Of course, this issue differs from social media users’ general objections to platforms’ content moderation efforts because, in this case, it is state governments – rather than privately owned social media platforms – that are restricting moderation.

Several civil society organizations have written amicus briefs effectively siding with NetChoice, the trade association that represents some of social media’s behemoths, including Meta, Google, Snap Inc., TikTok, and X. While it may initially seem counterintuitive that so many of Big Tech’s staunchest critics sided with the very entities from whom they seek greater accountability, they understand that platforms’ exercise of editorial discretion has the power to steer online spaces toward safety, inclusivity, and democracy.

Conversely, X’s hands-off approach to addressing misgendering and deadnaming affords us a horrifying glimpse into what social media platforms could look like if the NetChoice holdings favor states’ restriction of platforms’ content moderation efforts: spaces in which platforms are required to carry the most odious and harmful content on equal terms with all other content – and where no members of marginalized communities can feel welcome or safe. This image is anathema to democratic values, and should alarm us all.

While the future of trust and safety hangs in the balance, it is clear that online safety and democracy alike rely heavily on platforms’ good-faith efforts.

When Elon Musk acquired Twitter and rebranded it X, he voiced his vision for the social media platform to serve as a “digital town square” and a bastion of free expression for all. Unfortunately, this promise has rung hollow to X’s LGBTQ+ users, and many others, who have watched the platform become a hub for the proliferation of hate, harassment, and abuse. While X was once the preeminent social media platform for organizations, government actors, journalists, and the public to engage around current events and key social issues, its increasingly hostile environment has been a factor in many users’ moves to rapidly growing competitor platforms like Bluesky, Mastodon, and Threads.

If X genuinely wants to advance free speech as its owner boasts, it must promote the safety and inclusion of all its users—not just its far-right voices. Rather than apathy and toothless policies, this will require an active commitment to good-faith moderation efforts and the enforcement of content policies that the law – at least for now – empowers X to pursue.

Authors