Across the US, Activists Are Organizing to Oppose Data Centers

Justin Hendrix / Sep 14, 2025Audio of this conversation is available via your favorite podcast service.

Demand for computing power is fueling a massive surge in investment in data centers worldwide. McKinsey estimates spending will hit $6.7 trillion by 2030, with more than $1 trillion expected in the U.S. alone over the next five years.

As this boom accelerates, public scrutiny is intensifying. Communities across the country are raising questions about environmental impacts, energy demands, and the broader social and economic consequences of this rapid buildout.

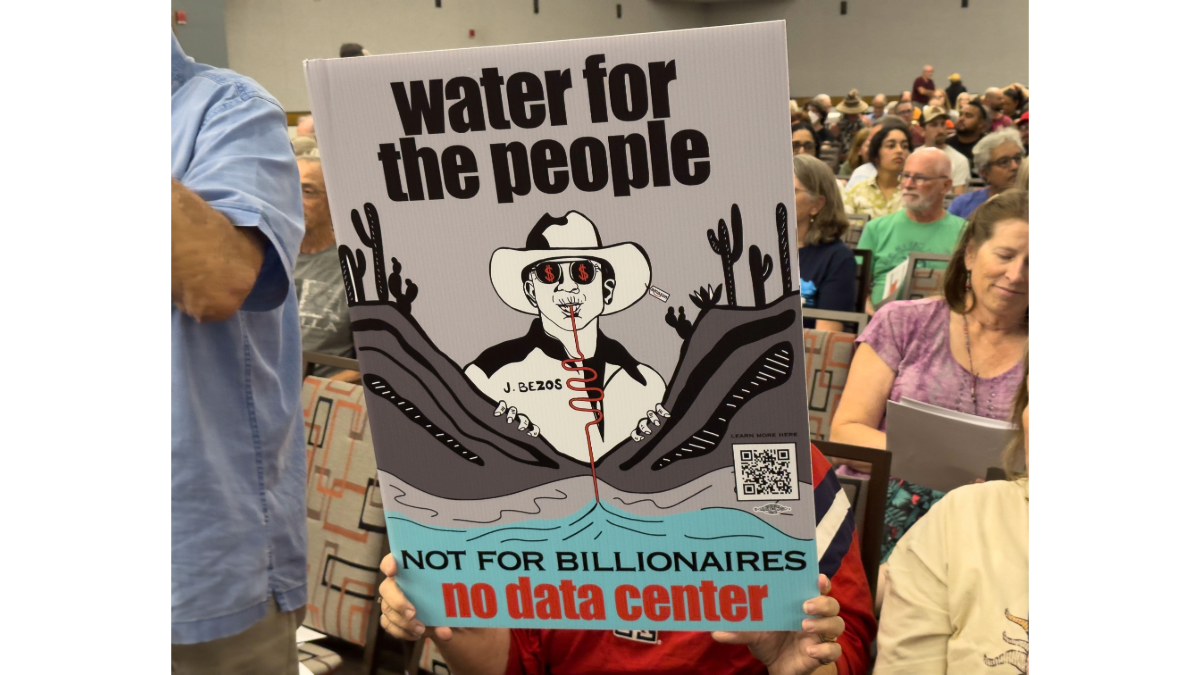

Community meeting at the Tucson Convention Center on August 4, 2025, a public forum to discuss pros and cons of "Project Blue," a massive data center installation proposed by Amazon Web Services, one of the largest economic development projects ever considered by the city and county.(Photo by: Wild Horizons/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

To learn more about these debates—and the efforts to shape the industry’s future—Justin Hendrix spoke with two activists: one working at the national level, and another organizing locally in their own community.

- Vivek Bharathan isa member of the No Desert Data Center Coalition in Tucson, Arizona.

- Steven Renderos is executive director of MediaJustice, an advocacy organization that just released a report titled The People Say No: Resisting Data Centers in the South.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of the discussion.

Justin Hendrix:

I'm so pleased to have the two of you here. We're going to talk a little bit about some of the work that both of you have been doing with regard to data centers. But Steven, I do want to start with you and just how you come to this work, why MediaJustice feels the political battle over data centers is one it needed to wade into?

Steven Renderos:

I'll give you the quick context for MediaJustice. We historically were a Black-led media accountability organization. We were founded way back in 2001, and at the time, the focus was really to try to organize communities of color to fight back against the corporate consolidation of the media system. And that was particularly in the Bay Area. And eventually we took a national focus around that, but broadened our horizon to focus on broader sets of issues related to communication rights, right as the internet was coming of age. And as technology continued to evolve in large part pushed forward by the internet, our focus also shifted moving from fighting on affordable broadband issues to fighting against high-tech surveillance to hate speech on online platforms. I think the common through line through all of that work has been really seeing the role that giant corporations are playing and really defining what media and technology does in our lives.

So last year we launched a new strategy called Shifting Terrain. And in that strategy we're hyper focused on how do we actually build the power, community power we need to weaken these giant corporations. And data centers became very relevant front of the struggle because if you pay attention to what Microsoft and Google and Meta, where they're investing the bulk of their capital, it's in building these data centers. So you have to ask yourself why. What's behind that for them? It's clearly an interest area because they're popping up in just about every community you can think of from rural to urban centers. And so it felt like an important place for us to be paying attention to.

And what we found is that in this moment where AI is everywhere, AI relies upon infrastructure, real brick and mortar infrastructure for it to accomplish like some of the more complex things that tech giants like Sam Altman and Elon Musk saying these devices, these tools can do. And it's a place where it's a raw deal for the communities that are building them. They're coming in with promises of jobs and economic development, but the reality is far different than that. And so we took it upon ourselves to play a role in helping to build the community resistance and build on top of community resistance that's already there to try to fight the expansion of this infrastructure, which really presents a bad deal for the communities that build them.

Justin Hendrix:

Vivek, I want to bring you in. You've just had experience with this type of battle. I want to ask you to just inform the listener a little bit about what's gone on there in Tucson, about Project Blue, and where things are at the moment.

Vivek Bharathan:

Sure, yeah. Thanks Justin for having me on. So yeah, I'm a member of the No Desert Data Center Coalition, which is a group of individuals. We don't have any formal organizational support and we're a group of Tucsonans who came together once we heard about this massive data center that was going to be built just east of Tucson, sitting on 290 acres of living desert space. And this happened, it started, I mean what we know now is that this started a long time ago in 2023, but from we found out about it in June and we found out about it shortly before the Pima County Board of Supervisors and Pima County is where Tucson is. Before the Board of Supervisors voted to sell this parcel of land of 290 acres to a corporation called Beale Infrastructure, which is a subsidiary of this huge private banking firm called Blue Owl.

And the crux of it was basically that they wanted to build this giant data center. They wanted to partner with TEP, which is Tucson Electric Power, which is a private utility electricity company and with Tucson Water, which is a public utility that supplies water to Tucson and they wanted to use these data centers. They're basically these giant computers sitting in these warehouses and holding all of our cloud infrastructure. So when you think of the cloud, it's not some abstract thing sitting out there. It is these very much real computers that occupy these giant buildings all over the country and all over the world. And this one was particularly egregious because these things generate a tremendous amount of heat and they want to put this thing in the desert, which is already hot. In June when we found out about this, I think our temperatures were exceeding the 105 already and they went up to 114 over the period of this campaign and they wanted to cool it down with the precious water that is extremely scarce and that we're losing some of it.

They wanted to use potable water for some of it. They wanted to use reclaimed water for it that already has purposes and uses within Pima County. So that's how we found out about it. A bunch of us gathered, we went to the Board of Supervisors meeting, encouraged them to vote no. Unfortunately, they did not. They voted a three-two to sell the land. I am just going to summarize here, but I would like to get back to the dynamics of that meeting a little bit later. And so at that point we knew that it wasn't just a group of us trying to get our Board of Supervisors to vote no, it became very real that this was going to be a campaign. So we organized with other coalitions that have already been forming in Tucson since inauguration and that predated inauguration who've been organizing here for decades.

And we came together and through a series of protests through attending the public information sessions that the city of Tucson put together, which were really propaganda sessions that the city manager facilitated, we got the city council to vote no to annex the land that was required in order to get Tucson Water to supply water to the project. Unfortunately, well, we were successful in getting city council to vote no. So that was a huge win and that's the one you all heard about and that made a splash. Unfortunately, now, we're in a position where TEP has over the wishes of the people of Tucson come into an agreement with Beale infrastructure, that corporation to go ahead and build the data center just without water. We're not sure what exactly that looks like. We're not sure if they know what that looks like, but right now the processes with the State Corporation Commission, and so that's going to be a much tougher fight for us. We're going to have them mobilize statewide for that.

Justin Hendrix:

And when you say without water, you mean without water from the public utility there?

Vivek Bharathan:

Yeah, that's right. We're not sure if they're trying to find water of the same volume elsewhere, it's unlikely that they will be able to do that or if they're changing up to another form of cooling these massive data centers that they're about to build.

Justin Hendrix:

And one thing that's been interesting to me in observing some of these points of opposition to data center development across the country has been that the politics aren't exactly as one might predict. Is that true there in Tucson?

Vivek Bharathan:

It's absolutely true, and I think it's because the bottom line is we were able to lead with your power bills and water bills are absolutely going to go up. This is what we know from other parts of the country, including our neighbors in Phoenix. What we know from Phoenix is that they've faced a tremendous amount of energy demand increase over the last few years and what we've learned is that data centers cause 94% of that increased demand. If you take them out of it, just consumer demand, household demand remains pretty flat. But those consumers, because these are private electric companies in the state including TEP and the one in Phoenix, all they have to do is announce a rate hike and take it to the State Corporation Commission. And this corporation commission generally approves all these rate hikes. So we were able to explain that to folks.

There's the power issue, there's the water issue. Water is a precious resource, it's a very incredibly scarce resource in the desert, and these were some of the easiest conversations I had with folks within 15 to 30 seconds as soon as we made it clear that they wanted to use Tucson Water for this giant project to just cool these computers and that power bills would go up, those were winning arguments. Additionally, there was the secretive nature of the process just in terms of being hidden by NDAs.

We didn't know who the company was until one of our fantastic local newspapers, Arizona Luminaria broke that story that it was Amazon. Just the nature of these meetings were... What struck me about that initial Board of Supervisors meeting where they voted to sell the land was that everyone who had time and space to talk and engage with the Board of Supervisors to speak at length, to present their crappy PowerPoint presentations and get questions from Board of Supervisors, all of them were in favor of the project. They were all speaking on behalf of the project. They wanted it to go through. Everyone who spoke against the project and who wanted the Board of Supervisors to vote no, we're community members. We were not paid speakers. We were not paid to be there unlike the folks who were speaking on behalf of the project. And we were given two minutes to state our case, and I think we did a fantastic job under those circumstances.

Justin Hendrix:

Steven, I want to come to you and bring us over to the American South. You write in the introduction to your report, “From Bessemer, Alabama to Memphis, Tennessee local communities are showing up to call out the public health, environmental and economic harms of data centers and the bulldozing of democratic processes to green light them.” Tell us a little bit about what you've observed in these five states. Take us into perhaps one of them. I mean, we can pick one out to focus on. We've talked in this podcast before about what's happening of course around South Memphis. Folks who are listening might be aware of the very large Facebook data center that's under development in Louisiana and other projects in Georgia and South Carolina, Mississippi and elsewhere. But take us into the south.

Steven Renderos:

The story of this report, which is titled “The People Say No,” is both a story about in this moment of huge technological innovation and a push towards an AI arms race in the way that the president has talked about it in his AI action plan. This is a story about who gets sacrificed along the way in that arms race. And for us, it was important to highlight the south both because it is a region of with a historical context of deep extraction, and it's also a region of historical resistance to that extraction. And around technology, the same story is playing out. It is both the place where many tech companies are moving towards. So it felt important for us to highlight that the south is now becoming the next sacrifice zone and will become the heart of a lot of data center infrastructure. And we're not just talking about the supercomputers, the warehouses for these computers, but we're also talking about the energy that's going to fuel them.

What we're seeing all across the south is the construction of new methane gas pipelines, more gas refineries, coal plants coming back online who have been shut down because of their harmful polluting effects to the local community. We're seeing the construction now an increase in nuclear reactors coming online after many decades of a decline, and it's where this infrastructure is being built. That was particularly important for us to highlight. I think Memphis is a great example in a historically Black neighborhood, Boxtown, where Elon Musk decided to build his giant, I think it's called Colossus Data Center. And in order to power it, they had been approved to run gas turbines. They decided to build 35 of them because that is how tech companies operate. They will come in and they will consistently push the boundaries and they will do so in a way and in a place where cancer rates are already high enough as it is in Boxtown.

And there's been a long historical environmental justice fight in that community, in the region known as Cancer Alley down in Louisiana between Baton Rouge and New Orleans where many extractive plants have been built. It's also the place where Meta is investing a deep amount of infrastructure, and so it's only going to make those conditions worse and it's happening in communities that are historically Black. And I think that's a really important thing to call out. These tech companies are very intentionally building these things where they think there will be a path of least resistance. But what they're coming to find out, and even in Tucson and all across the country we're learning, is that there is resistance possible to these things because one of the myths that tech companies sell us that many politicians actually adopt is that these things are inevitable. The AI age is inevitable.

The construction of these data centers is inevitable. In fact, I actually remember in some of the messaging from some of the city officials in Tucson, they were very much echoing this understanding that like, "Hey, look at Phoenix. They've built over a hundred data centers there. We only have seven. The industry is coming here. We got to prepare and we got to make the best deal possible." And what the No Desert Data Center Coalition proved is that in fact you can say no. No is a complete sentence and you can push back. And that's happening throughout the south as well from North Carolina to Bessemer, Alabama to what we're seeing the pushback in Memphis to folks organizing in Baton Rouge, folks organizing in Mississippi.

And we wanted to call attention to that. And we also wanted to use this report honestly as a way to throw up the bat signal so that folks can pull us in as an organization with a history of organizing as our primary methodology. We want to be in the fight with people with groups. So we definitely encourage groups to read the report and to reach out to us if you're looking to get down in a fight against a big tech corporation because when you organize, we can win.

Justin Hendrix:

I want to focus on one of your calls to action, which Vivek has already brought up, the issue around NDA's secrecy. It is, I suppose in their defense, a lot of economic development projects start with NDAs between corporations and local or other government entities, certainly with economic development entities, but in particular, these NDAs appear to be a sticking point in communities across the country, particularly when it comes to energy usage and generally plans, who the owners are ultimately of these massive facilities. That seems to be a common thing that the biggest corporations want to hide their identity as long as they possibly can in these processes, I suppose, in order to fend off political opposition or more scrutiny perhaps. Vivek, can you talk a little bit about how you all negotiated that, how you got to getting information and what that process of secrecy and trying to pierce it meant for you as an activist?

Vivek Bharathan:

Yeah, that's a really good question, and I think I'm still, someone asked me a few weeks ago whether it would've made a difference if we didn't know it was Amazon. And I'm honestly not sure because I think the three main points we led with were the power of the water and the process. So no matter what this process was completely one-sided. Even if we had known it was Amazon, it would've still been one-sided. It just, it did help... It did make a difference just to know that the company behind this was a secret and we didn't really understand why that was necessary.

And most of all, we didn't understand how it was possible for our public institutions to actually agree to a process where that was not only hidden from us the public, but it was hidden from them. The county administration knew who the corporation was. Our elected officials agreed to a process that the county administration set up for them where they didn't have all the information that they needed to vote, but they voted anyway. And I think that's the dynamic we're seeing across the country is that municipalities are engaging in this race to the bottom that completely betrays their constituents and benefits these resource extractive corporations.

Steven Renderos:

It's interesting because with some history of organizing against companies like Meta and Google during the heyday of some of our work trying to pressure these platforms to be more accountable to its users, they often had the playbook of inviting you into their headquarters and asking you to sign NDAs. Meta was particularly famous for doing this. You would show up to Menlo Park and to learn about changes they're making to their content moderation policies and to their practices on how they deal with election disinformation, for example. And they'd want you to sign NDAs in order to get inside and be in the room. We always refuse to do that, because there's just no way you're going to tell me you're going to give me information and I'm not going to go back to my community and tell them what's going on. And this is us, an organization, a nonprofit organization, and we got to demand that standard should be there and above that for public officials.

So NDAs is very much a part of their playbook, but also, I think writing the rules is very much a part of their playbook. Trump's AI action plan was written by tech billionaires, and that's as true at the federal level, but also at the local level. I know Vivek shared with me how the local coalition folks were reacting to the city manager. I think he even mentioned it earlier where it's like the line he was pushing, the story he was telling was the story that was being directly shaped by the tech companies themselves. And I think it's interesting to note, I think around data centers as well that this is one of those issues that has tapped into something for people. And I'll say as a former Tucsonan, I still subscribe to the Nextdoor, think I've shared this with Vivek. I still get a digest of the top posts in my neighborhood and actually lived in East Tucson where the data center was going to be built.

And the top post a few months ago was a post about the project blue. And this is before anybody knew anything about Amazon. And I can tell you from experience, the top posts in that neighborhood are always missing dogs, coyote sightings and porch pirates. And here, as someone who's worked on tech issues for a while now, this is the first tech issue I can really think of that's motivated people to get up and show up to a city council meeting in the middle of the day. So I think that's really important to note because I think it's clear to people the connection between the infrastructure, the tech, and the harm that it will produce in a very material way if it's taking away my water, if it's taking away my electricity, if it's eating up all this land and we're just giving it away and it's happening in a way in which the public doesn't even get a say into, that's completely wrong. And that's motivating all kinds of people to show up to the fight, which is really exciting.

Justin Hendrix:

Well, let me ask a follow-up question there. Maybe wondering about how in the communities you looked at in the South or, Vivek, there in Tucson, the extent to which community concerns are voiced that go beyond just energy, electricity, beyond just the typical fears around construction or the siting of these things, are there broader concerns about AI's impact on labor, on the economy, on jobs, other types of concerns that you're seeing expressed, not necessarily by yourselves as activists, but by the citizens around you?

Vivek Bharathan:

Yeah, for sure. At one rally, someone walked up to me and was like, "Look, I'm a designer. I'm a graphic designer. I understand that there's not only an environmental impact because I live in the affected area. My parents live in the affected area, but I stand to lose my job because of facilities like this and because of generative AI." So I think there is that understanding among folks just by virtue of the fact that it was Amazon. When we found out it was Amazon, there were a couple of other angles to take too, including that Amazon works with Palantir on surveillance. It has been surveilling immigrants for years, which folks can learn more about in the No Tech for ICE report that Mijente put out a few years ago, but now they're going to be surveilling US citizens as well.

And that was a point we could make once we found out it was Amazon. Throughout this process, the local tribal councils and indigenous people communities were completely left out of the process and the Pascua Yaqui Tribe Nation and the Tohono O'odham Nation. And yes, so the answer to your question is we have had folks join us because they're apprehensive about the quality of generative AI as it stands its capacity to take jobs away. And yeah, just what exactly it is that we're giving up this many resources for for some folks who, like Tracy McMillan caught him just right as it's mid, it's just not the quality is not worth the resources that we're giving up for it and that our communities are asked to go up for it.

Steven Renderos:

In addition, I think something else that's really, I think, shaped people's understanding of this moment has just been what we've seen happen nationally politically. When a tech oligarchy shows up at inauguration and is sitting front row, that stands out, and they were a very key factor in the election of Donald Trump. And when you think about the agenda that the administration has pushed forward, technology has played a very central role, the complete displacement and firing of federal workers, many of whom are being replaced with artificial intelligence, the deployment of ICE agents and ICE operations all across the country. It's both the actual agents on the ground, but it's the technology that's being used like Palantir to identify people and to track people down to surveillance technologies that are being used by federal and local law enforcement agencies to target and criminalize protests. And so I think some people are definitely making that connections, particularly true in Louisiana where we have good relationships with groups on the ground in New Orleans who are fighting surveillance tech of different forms, but they know that the data that is collected through those technologies, it all lives somewhere.

Like Vivek said, cloud infrastructure is not things in the cloud, it's actual brick and mortar, it's physical and data centers are that site. And so folks are able to make that connection. But it's also what's interesting about data centers is it brings people from very different motivations to the table where you can build really interesting big tent like multiracial coalitions. And in a way, I've seen it, I think seeing how people engaged in the fight in Tucson and in Bessemer, the way that people are engaging in their local democracies, which feels really important in this moment when just democracy in general is progressing towards authoritarianism, that these local fights around data centers can be a way to also push back against that regression.

Vivek Bharathan:

I tell people sometimes it's like the Stefon character from SNL, it has everything. It really does.There's so many terrible things that we can all fight against.

Justin Hendrix:

I want to ask you a question about how you educate yourselves as activists around the technical claims that come along with data center development. I know there in Tucson for instance, a lot of the discussion as you've already mentioned was around water usage and there were different proposals put forward about first, of course, rely on water that would come from sources that also supply drinking water. But then there were various claims made about eventually moving to a closed system and being able to go with a mechanism that would allow for much less water to be used or wastewater to be used. I don't necessarily want to litigate whether or not those claims are necessarily true or not.

I'm more interested in asking you a different type of question, which is about that asymmetry of technical information about how these things are to work, how they may work in future, what the time horizons are for different types of upgrades. I mean, a lot of times it seems like the data centers get built and there are in some cases, as we've seen in Memphis, as you mentioned with the gas turbines, temporary solutions that are put in place. And the promise of course is that a cleaner technology will be installed eventually or built eventually to service those things. But how do you evaluate technical claims as activists? Who do you go to right now? Where are the sources of information that you can trust?

Steven Renderos:

It's a great question. For us as a, and I'll go ahead and out myself, I'm not a techie, I'm not a technologist. I am also not a policy monk. I come to this work as an organizer. That's my primary orientation. But one of the things that has really been key to our ability to organize around media and tech issues that as you're describing, Justin, are like a moving target where there are claims of one thing and evolving technologies that shift into something else, into something else, and there are new claims that we have to confront. One of the things that's been key to our success has been our ability to also build with other national organizations. As a racial justice organization, we have the ability to build on the ground with communities of color and to be trusted ambassadors of information for them. And we've been able to build bridges with national policy groups and research groups that are studying this in a myriad of ways.

And in Tucson, in fact, this was beneficial. When we took a step in to support the No Desert Data Center Coalition, part of what we did was really help them debunk a lot of the public messaging and the marketing from the developer. We did that by pulling in national allies like the AI Now Institute that has done a ton of research on the AI industry and industrial policy both here in the US but abroad. And so they're looking at the larger supply chain and bringing in that perspective has been helpful. But also, as we've been connecting with different communities, there are regional players like the Southern Environmental Law Clinic that is actually suing xAI at this moment and their legal expertise has been beneficial to learn from and build from. And so I think that's, we play that bridging role. I think bridging relationships, I think that's been key to our success. I'll give you the plug, Tech Policy Press. It's really helpful to have outlets that are out there that are writing about this.

And I'll say some of the... In Arizona, AZ Luminaria was very key. Their investigative journalism was very key to the community, being aware of what was happening. But frankly, one of the people that I started reading years ago that now is doing the roundabout with a book is Karen Howe, her writings on data centers in the Atlantic and in other places, I think was really key to shaping my understanding of what was happening. So we have to go out there and seek out the information because we're not the technical experts, but also we can build relationships in a way that allows us to connect the dots and key moments. And that's been our approach to it. But I also know in places like Tucson, and Vivek can speak to this a little more clearly, there's local expertise, people who understand many of the things that are being brought up. And Tucson is fortunate to also have a university in town. It's a university town, so you have academics and researchers that are actually focused on water and energy use that have been helpful thought partners as well.

Vivek Bharathan:

Definitely. One of those professors is Dr. Michael Bogan. He's been huge, huge in providing resources to us in terms of understanding water. Another organization that we're blessed to work with here is the Watershed Management Group, and they've been around for a while. They do trainings about for folks on rainwater harvesting, and they also have a lot to say about water policy and they work with the city. And so I think because water conservation is just such a part of our daily lives here and so much of a part of our messaging, it was really unfathomable to so many of us who've had to make adjustments to our lives to conserve water that the city would be prepared to give away so much of that work, the county would be prepared to give away so much of that work to this resource extractive corporation.

One thing I learned during this process is that over the past 20 years since I moved away from Tucson, I just moved back a few years ago after having grown up here, is that Tucson's per capita water use is on the decline. And Tucsonans have made a huge effort to limit our water consumption and there have been policies put in place to help that happen. So yeah, this would've given all of that away and that was just unacceptable.

Justin Hendrix:

Steven, obviously doing this report and then through your work with MediaJustice, you are in touch with many communities you're organizing, you're serving as a, as you say, bridge, but you're also in coalition across various groups. Are you observing a national infrastructure being built around data center opposition or the contestation of data centers? Does it seem as if that has coalesced?

Steven Renderos:

Yeah, it's coalescing. And I think what's going to be key in fighting data centers is maintaining some level of nimbleness. There is the way you fight centralization, and that's what we're up against. We're up against centralized opposition, big tech corporations that have control of infrastructure at multiple layers of the ecosystem. And the way you fight that is through some level of decentralization. So we're certainly a part of coalitions that are coming together, and I'll name a couple like the Athena Coalition. We're a member of a data center working group with some national organizations that's helping to be a repository of information sharing on what we're seeing out in the ecosystem. There's also a cross state working group of state-based organizations that are fighting data centers much in the way that Vivek has brought up where the fight in Tucson has evolved into. Now, it's a state fight because we're dealing with a state corporate commission.

And so there are places where those groups are coming together. Another thing I think I'll shout out, and this is more of like how do we create informal opportunities for relationship building. We're going to be hosting a gathering next year in the spring called Take Back Tech. It's the third of its kind. And actually, I think Vivek went to the very first Take Back tech, which took place in San Jose back in 2019, and we hosted one last year in Chicago in the summer. We're doing another one next year. And that's going to be a space I would imagine a lot of groups on the ground that are not necessarily tapped into state organizations or big national organizations. That's going to be a space where they can come and build relationship with other groups that are moving similar work and to share relationship and share resources.

But it is coalescing in different ways. And I think that one thing I'll throw out there is that there's just, with data centers, even just in the south alone, and we said this in the report, there's $200 billion worth of data center projects moving just in the south. And that's not to speak of what's moving throughout the United States, and that's certainly not to speak of what's moving globally. And so the fight is everywhere, and I do hope that more and more infrastructure comes together that helps to weave these fights together. But what we also need more than anything really though is a national story.

And I think one of the things we were seeding through this report, and I'll just repeat it again, is that there's nothing inevitable about these data centers. You can and should push back. You can and should say no. And we hope that the demands, even though they're specific to a report about the south, are also as true in every other region in the country. You can say no to these things. You can demand a democratic process where there is not one happening. You can connect data centers to the extractive surveillance tools that you see in your backyard, even if you don't have a data center being built in your community. So encouraging folks to organize, to connect with us if they'd like.

Justin Hendrix:

I want to maybe just ask you one last question, which is to that point about a national narrative. I mean, there is a national narrative that appears to be operative at the highest levels at this commanding height to the government at the moment that building this infrastructure is not only in the country's economic interest but also in its national security interest. A lot of the policy around artificial intelligence is framed in the race with China, and there seems to be almost a sense of we need to clear the decks, steamroll obstacles, and perhaps even make sacrifices so that the country can maintain its edge against another superpower.

Steven Renderos:

I think what's important to recognize, and I think this will feel especially true for people who have been dealt a raw deal, whether that's through systemic discrimination and racism, through underinvestment, through the loss of economic industry, seeing the economic powerhouses leave your town and take your jobs elsewhere, I think there's a common experience of there are people in these rooms that we don't get to be a part of that get to make decisions about what happens to our lives. And I think the national narrative being like, this is so imperative to the national security of the United States, that has been a story that has been very intentionally and deliberately positioned by tech giants themselves.

They are saying our economic interests is the same as the national interest. And what they're really saying is my ability to generate more profit to, in the context of Elon Musk, to become the world's first trillionaire. That matters more than any other consideration. That the push for AI to win the AI arms race matters more than to poison people in South Memphis. That's what they're saying, that there is a necessary sacrifice and that sacrifice is a human sacrifice that certain people are worth sacrificing for technological progress. And I think it's indicative, I think of a moment in time when you think back to the construction of the interstate highway system throughout the United States. It was like urban planners, engineers, Robert Moses in New York, very intentionally bulldozing through Black and brown neighborhoods all over the country for the sake of products.

And it's that sacrifice that we're seeing happening again around data centers. So I guess what I would say is that no matter who wins the AI arms race, whether it's China or the United States, the people who will lose are communities of color, the people who will lose or the communities that have historically been under invested in. It's the communities that will be dealt the raw deal being told that all these jobs are coming to town. Come to find out that in the fine print, it's no more than 50 jobs and most of those are contract jobs, so they're not even actual technical employees of many of these companies. Those are the communities that will be sacrificed and lost for the sake of someone else's technological products.

Vivek Bharathan:

I said a little earlier that these are the kinds of deals that our municipalities are engaged in in a race to the bottom, and that's because they're cash strapped. We do need economic development, and I think for us as No Data Center Coalition, we're starting to get a little more proactive in terms of figuring out how to reach out to other folks and other organizations in our community to think through what economic development can look like in a way that supports our community and is sustainable. Much of the way that our municipalities at the county and city level, the administrations are going about economic development. From what I understand, this being my first foray into local politics here is that they're chasing these big projects that ostensibly come with a lot of money, and they also come with a lot of blood, and like we've said already, they come with a requirement to sacrifice a lot.

We want to think through, what are some economic development projects that we can engage in here and be proactive about that are smaller? What are the kinds of things that folks in our communities could invest in? And I'm not talking about tax revenue, I am not talking about where can we allocate tax revenue better, but what are projects that our communities, that the county and city can facilitate, that people who have a stake in our community, who live here, who are invested in continuing to live here, who want their children to have a choice about whether or not they live here, what are those projects that we can put our own money into and see some return on investment?

I've been a non-profit worker. I've been working in higher ed for most of my career, and I have a very small retirement account that's in 401k portfolios, and a lot of those are in tech firms. Apart from just how I feel about this, I have zero material interest in my money being invested in those places if those same corporations are coming and extracting resources from my community and pushing my power and water bills up, like zero material interest. So in a second, I would pull my money from there and if there was an opportunity to put it into something local that I knew would support myself and support my communities.

Justin Hendrix:

Sounds like you're trying to cobble together essentially an alternative future for your community, one that's different from the one that Silicon Valley wants to sell you.

Vivek Bharathan:

Yep, that's exactly right, and we can do that together.

Justin Hendrix:

Steven, Vivek, thank you so much for joining me.

Vivek Bharathan:

Thanks so much for the opportunity, Justin. It's been great to chat with you. Thanks, Steven.

Steven Renderos:

Thank you, Justin.

Authors