Many Latin Americans Living Near Data Centers Don't Feel Welcome in the Future

Pablo Medina Uribe, Francisca Skoknic, Alberto Pradilla, Laura Scofield, Justin Hendrix, Julia Gavarrete / Sep 12, 2025This article is part of the project "The Invisible Hand of Big Tech," led by Agência Pública and El Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), with the participation of 15 other organizations — including Tech Policy Press — from 13 countries. Read more about the project and find other articles in the series here.

Illustration by Alejandra Saavedra.

Sandra García, a 38-year-old factory worker who lives with her husband and son, opens a faucet in her home, but no water comes out. This has become the new normal for her and many of the inhabitants of Colón, a small municipality in the central Mexico state of Querétaro, a region increasingly hit hard by drought. In May this year the local water authority, Conagua, declared that 17 out of the state’s 18 municipalities had not received enough rainfall, leaving its dams running dangerously dry.

The situation was so bad that the local government began to ration water with some families only getting access one day out of three. García cannot always wait for her share and makes the trek to her landlord’s house to fill jerry cans just to get by.

While many residents of Colón make the connection between failing rains and dry taps, fewer are aware that they face a major new industrial competitor for their scant water resources. The state of Querétaro is fast becoming famous for another thing: it is one of the Latin American hubs for the rapid expansion of the data center industry. According to the Mexican Data Center Association, there are 14 facilities in the state. The local Development Secretary listed 19 permits responding to a public information request by our reporters. Most of these datas centers are in Colón or El Marqués, both municipalities near the regional capital, also called Querétaro.

The cloud is a loaded image that evokes weightlessness and the idea that we are pulling down the digital services that many of us rely on from some ethereal space. But the reality of the cloud could scarcely be more grounded. Google Drive, OneDrive, Amazon Web Services (AWS) and others require gigantic physical infrastructure. The nodes in this network are data centers, buildings stacked computers called servers that store reams of information from your personal details, to the images and texts that load when you doom scroll on social media or the encrypted data that allows you to bank online.

Data centers have existed for decades but the full implications of this industry are only now beginning to come into focus. Since the emergence of generative artificial intelligence, new, more complex, and more expensive AI data centers have been built, or are planned, across the globe. This new generation infrastructure requires generally more power and water than their earlier counterparts. These greater demands are driving a global expansion that makes comparatively less exploited regions like Latin America, a target for the biggest technology companies since many countries have vast natural resources, cheap energy and governments willing to lower taxes for these companies so as not to miss out on the future.

The real-world industry that lies beneath the cloud is more than just the Big Tech titans in the US and its counterparts in China. It also includes actors from real estate, construction, energy and hardware. And this industry has been investing in strengthening its relations with national authorities, often influencing regulations that will later benefit them. Latin America, with its mix of fragile governance and resource riches is now witnessing what this unprecedented infrastructure campaign means at ground level.

Data center companies argue that AI is the future of the economy, and that countries who refuse to embrace its potential will be left behind, missing out on tax revenue, jobs and services. Critics who warn that the industry consumes water and power at the expense of communities and the environment are told that AI will solve these problems in the near future as it advances sufficiently to develop new technologies.

At the heart of the construction campaign in Latin America is an industry wish list around deregulation and tax cuts and an unproven economic manifesto promising future prosperity. For nine months a coalition of 17 newsrooms in 15 countries have used freedom of information laws, confidential sources and community reporting to capture how this wish list has been pursued and to test the promises made against the reality on the ground in Brazil, Chile, El Salvador, Mexico and Paraguay. The resulting investigation, “Big Tech’s Invisible Hand,” led by Brazil’s Agência Pública and El Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), found that promises of hundreds of thousands of direct and indirect jobs to be created are unfounded; economic benefits for local economies remain unproven; that industry claims of renewable energy disguise the deployment of new fossil fuel facilities to power data centers; and that multinational corporations’ complex structures deflect regulation and complicate efforts to monitor environmental impacts and resource consumption.

Time and again this investigation found that promises of near-future solutions were being made to push through decisions that do not make sense in today’s technology and resource context.

Keep it cool

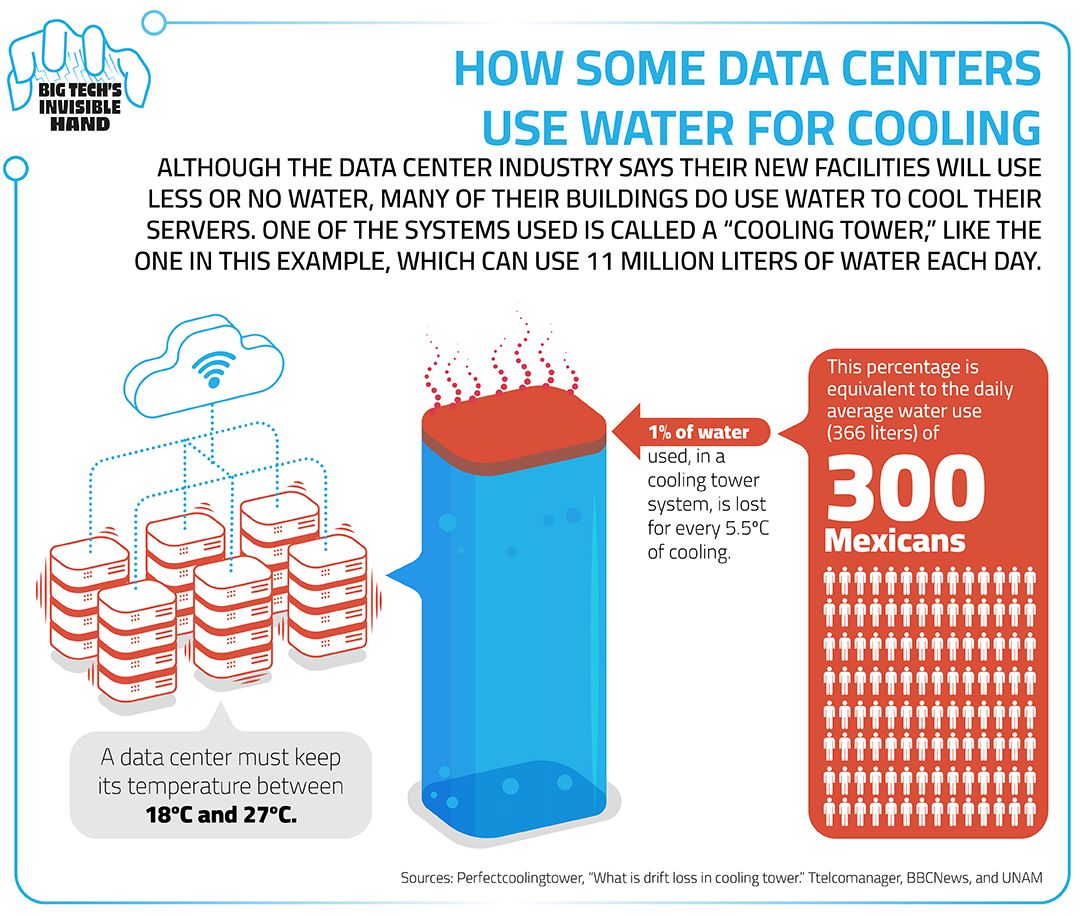

One of the central design challenges for data center providers is cooling. This is where the need for water comes from. Servers are comprised of boards with processing units that provide the compute power. These servers run constantly and must be kept within a stable temperature range, most often using cooling systems that rely on heavy water consumption Central Processing Units (CPUs) were the key component in data centers providing cloud services until recently when General Processing Units (GPUs) were found to be much more effective at meeting the computing demands created by AI. The new generation of AI data centers run far hotter and therefore require far more water.

“Water is often the last consideration when making siting decisions for data centers because it’s cheap compared to the cost of real estate and power,” Sharlene Leurig, a managing member of Fluid Advisors, a water consulting firm, told Bloomberg.

Infographic by Oldemar González.

When authorities do question water consumption, then companies, including Microsoft, argue that they are solving the water issue by creating a “closed-loop system” in which, theoretically, no water evaporates, so there is no need for continuous water access.

In Mexico’s Querétaro state, our coalition partner N+ discovered that both the state and federal governments launched a new strategy to attract data centers, despite reports from the Comisión Nacional del Agua, Conagua (the dependency of the Ministry of the Environment in change of regulating the use of water), which recommended not granting new water-use permits. The state capital faced its worst drought in a century in 2024 –when 14.8% percent of the population lacked drinking water and farmers struggled to irrigate crops.

N+ found that Big Tech companies and international agencies worked together to present AI infrastructure as part of the solution to water shortages. Microsoft partnered with United Nations agency, UN-Habitat, in a joint call for an 82 million Mexican pesos (about $4 million) investment to boost the local economy in Querétaro. The accompanying report, coming after visits to eight communities, identified drought as one of the main challenges. However, the report did not recommend investments to solve this drought. Instead, it recommended investing in infrastructure for the region, such as paving roads or building a roof for a town square. The report claimed that “data centers represent an opportunity for the socioeconomic transformation of the state of Querétaro, and more specifically, for the municipalities of El Marqués and Colón.

Despite the international backing and the resources of Microsoft, it has made no investment in infrastructure to combat drought or any other socioeconomic problems in the state, as this investigation verified by visiting seven of the eight municipalities mentioned in the report and talking to local authorities. However, Microsoft did build a “data center region” in Querétaro, which began operations in early 2024.

This investigation reached out to Microsoft and asked about the purpose of this report, and whether its data centers could aggravate the water shortage in the area. Microsoft replied with a link to a fact sheet.

We also reached out to Amazon, a company which announced this year that it would launch a data center region in Querétaro, to ask about the water use of its data centers in this state. The company replied saying that this data center region will use a design that will not use water for cooling. They added that this will get them closer to being water-positive by 2030.

In Chile, it is another of the world’s richest companies that has led the way in constructing data centers. Google built a facility in 2015 before announcing, in a press conference with then-President Sebastián Piñera and some members of his cabinet, a $140 million expansion in 2018. By the time the tech giant announced plans for a second data center on the outskirts of the capital, Santiago, it already faced resistance. The plans for public protests and local authorities complained at the potential scale of water consumption. (See full story by La Bot, a partner in this investigation here).

The dispute reached the Chilean courts, which revoked the license for the second facility, after which Google committed to drafting a new plan for a data center that would use waterless refrigeration.

The court decision and the apparent concession by Google was celebrated as a win by campaigners concerned at the impact of runaway AI infrastructure but reporting by our partner LaBot shows that the Chilean government had quietly allowed the data centers constructors to bypass environmental assessments and gain permits.

The government decision, which was not made public, ended the need for impact assessments that are meant to ensure that resource consumption is clarified and that communities are consulted on the potential effects of developments. When LaBot raised questions about it, Chile’s environment ministry acknowledged the change and stated that being able to assess the amount of water consumed by data centers would require new regulation.

The battle over data centers in Chile has led to an emerging awareness of the potential harms and in turn to a questioning of who this infrastructure actually benefits. While some data centers provide services to nearby communities -- like higher speed streaming television -- AI data centers can be dedicating their compute to the training of Large Language Models like ChatGPT with little or no benefit accruing to local people or economies.

Half the data centers in Brazil, including those in planning, construction and operation, are in the state of São Paulo, mainly around the city of Campinas, according to data obtained by Núcleo Jornalismo, a partner of this investigation. This number includes both AI data centers and also older facilities, according to information from Data Center Map, which plots site locations worldwide. This part of São Paulo faces regular water crises, the most serious came in 2014 when many municipalities in the state, including Campinas and the city of São Paulo, faced extended water rationing.

Other locations identified by the industry in Brazil have faced similar droughts. Data obtained by a freedom request by Agência Pública, another partner of this investigation, showed that nine of the 14 cities slated to host new data centers, were classified by the Water Risk Atlas as at medium high overall water risk, and the other three are high risk. Those high-risk cities, include Campo Redondo, in the state Rio Grande do Norte; Igaporã, in Bahia; and Caucaia, in Ceará—all in Northeast Brazil. TikTok is building a data center in the latter municipality, even though it can be expected to worsen the drought in the area, according to a report published by the Intercept Brasil.

This investigation reached out to Luis Tosse, vice-president of the Brazilian Data Center Association (ABDC), for comment, among other things, on the impact of water consumption by data centers in areas with serious shortages. Tosse said that “we have water available,” and therefore this shouldn’t be considered a problem in Brazil. Andrei Gutierrez, president of the Brazilian Association of Software Companies (ABES), added that “it’s the same thing as saying: ‘ hey, we’re not going to build a road because the road makes the soil waterproof.’ Do you understand? I think it’s all a matter of needing planning.”

With the exponential growth of data centers, even if each individual facilities uses less water, more energy is going to be needed to power them. The scale and pace of this infrastructure boom is expected delay or reverse the energy transition away from fossil fuels and deepen the climate crisis, putting water-stressed areas at even more risk.

Keep it on

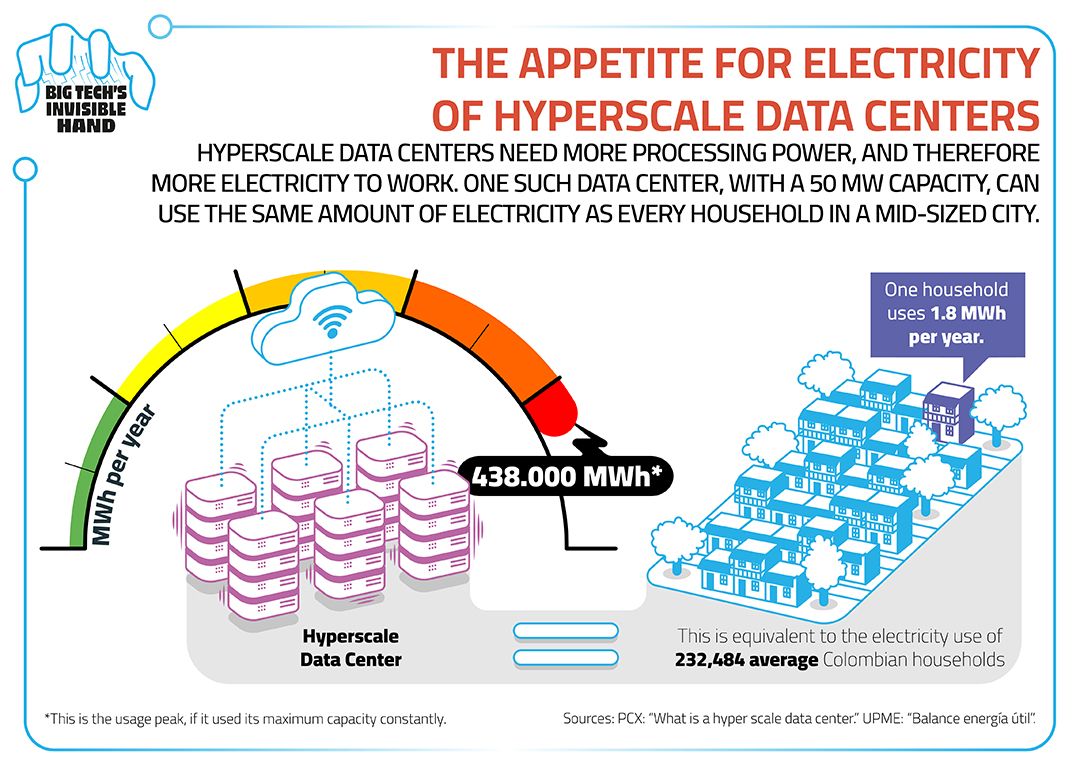

The energy consumption of AI is difficult to calculate, each individual query depends on various processes created previously, whose costs are difficult to individualize. the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated that a traditional Google search consumes 0.3 watt-hours. On the other hand, a ChatGPT query, on average, consumes 2.9 watt-hours.

The IEA published a report in which it calculated that data centers consumed around 1.5% of all of global electricity production in 2024. This is equivalent to 415 terawatt-hours. The IEA said it expected this number to more than double by 2030, a forecast which other experts judged to be conservative.

Infographics by Oldemar González.

Ireland deploys the highest share of overall electricity production into data centers at 21% in 2024 –mainly by burning fossil fuels. This proportion led Irish authorities to restrict new data centers around the capital, Dublin, out of fear of creating blackouts. Data center companies claim they are solving this problem. Meta, which is one of the world’s main data center players, has five facilities in Ireland (Data Center Map lists 133 data centers in this country). But they also have offices in the country, where they said that they had partnered with Brookfield Renewable Energy Partners “on a long-term renewable energy supply agreement to provide 100% renewable wind energy to the Clonee Data Center and Meta's Irish offices.”

An accurate assessment of energy use by sector is prevented by the companies themselves who claim this information is an industrial secret. Data from Cushman & Wakefield, a real estate firm, shows that, in 2023, the US and China were the countries in the world that used the most electricity to power data centers, as measured by megawatts capacity (1 megawatt, or MW, can power about 1,000 homes). This same data also shows three Latin American cities among the global top 50 electricity usage by data centers.

The city of Querétaro in Mexico made the list with a capacity of 150 MW consumed by data centers; São Paulo, in Brazil, with 122 MW; and Santiago, in Chile, with 61 MW. However, these numbers are changing fast, and it is difficult to give a precise updated figure. For example, a report from JLL, a real estate company close to the data center business, claims São Paulo, in 2023, had a 670 MW capacity for data centers already in operation, with an additional 382 MW capacity under construction and a further 388 MW capacity planned.

Agência Pública asked the Ministry of Mines and Energy for a list of all data centers in Brazil that requested access to the country’s basic energy grid, along with information on how much energy they consume. The response included only 22 data centers. Thirteen of the 22 requested confidentiality (as the country’s law allows them to do) of their energy use data, so the data was not made available. Among those requesting non-disclosure was TikTok, for the facility it is building in Caucaia. Data obtained by Núcleo with Data Center Map shows there are an estimated 170 data centers in Brazil, a number that includes AI facilities as well as older ones designed solely for data storage and processing.

While an accurate picture remains obscured by secretive industry practices and incomplete public data, the pressure from some of the richest companies in the world to expand electricity production is intense.

In 2024, Mexico’s Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) announced that it would increase Querétaro’s electrical grid capacity by 50%, citing the building of data centers in the region as one of the main drivers. The Commission announced a new power station, El Sauz II, which uses gas to generate electricity, adding more climate emissions. In an email sent to this investigation, Ascenty said: “The claim that the installation of new data centers in Querétaro, including those developed by Ascenty, would have motivated the construction of a new fossil fuel-powered plant is unfounded.”

In an interview with N+, Arturo Bravo, General Manager of Ascenty Mexico (one of the data center companies in Querétaro), said his company finances part of the reinforcement work needed to cover the electricity demand of its data centers, that it is constantly talking to CFE and CENACE (the National Energy Control Center), and that its petitions for electricity demand are always accompanied by studies.

Digital Realty Trust, which has a 49% stake in Ascenty, said in response to written questions sent via email by this investigation that “the total capacity at Querétaro is 8 megawatts (MW) - <0.01% of Mexico's total reported grid capacity (total installed capacity of ~89 gigawatts (GW) in 2023.”

While some data centers promise to use renewable energy—such as DataTrust in El Salvador which says it uses photovoltaic energy for its power, an assertion that has been impossible to verify— fossil fuel consumption keeps increasing.

In the US, the rapid development of data centers is driving a surge in demand for electricity that the Trump administration intends to meet by burning more fossil fuels. The US AI Action Plan released in July and an Executive Order on “Accelerating Federal Permitting of Data Center Infrastructure" both seek to clear regulatory obstacles, including environmental protections.

In last year’s environmental report, Google admitted that its greenhouse gas emissions have increased by 48% since 2019, mainly due to “increased data center energy consumption and supply chain emissions.” In the same report, Google said that “as we further integrate AI into our products, reducing emissions may be challenging due to increasing energy demands from the greater intensity of AI compute.” The company now assesses its much-vaunted net-zero goal in 2030 as “extremely ambitious.”

A Guardian investigation last year found that the emissions from data centers owned or operated by four of the largest tech companies’ in the world, Google, Microsoft, Meta and Apple, were potentially 662% higher than they officially reported.

Data center associations contacted by this investigation deny that the industry is looking to build more fossil fuel energy plants. Gutierrez, from ABES, in Brazil, said: “I don't see anyone building data centers wanting to encourage the use of thermoelectric, coal energy, diesel energy, which is more expensive.”

In their written response, Digital Realty also said that their company “has a validated Science Based Target initiative (SBTi) to reduce Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions in accordance with climate science.” And that Digital Realty “has further committed to climate neutrality for its European operations by 2030 in accordance with the Climate Neutral Data Centre Pact. In 2024, the company matched 75% of its global energy footprint with clean electricity, including 185 data centers matched with 100% clean power. Digital Realty has executed more than 1.5GW of renewable contracts to support our decarbonization efforts.”

While Brazil’s hydroelectric resources mean its grid is greener than most countries’, with 86% of the electricity coming from renewables and 64% from hydroelectric plants, climate change has affected rainfall, so energy production by thermoelectric plants has grown in recent years.

The scale of the data center explosion has brought nuclear energy back to the forefront. In Brazil, the minister of mines and energy, Alessandro Silveira, argued that the demand for new projects made nuclear energy the only solution, and that this would demand costly investments by the government. In the US state of Pennsylvania, the Three Mile Island power plant, which was the scene of the worst nuclear accident in the country’s history, will reopen to power Microsoft's data centers.

In Argentina, President Javier Milei has proposed a plan to increase the country’s production of nuclear energy to power new data centers, among other things. Nuclear is considered clean, since it does not emit carbon gases, but its development costs are much higher than other energy sources, it has a checkered history of accidents and there is no long term solution to nuclear waste, making it very controversial among environmental experts and activists.

Countries with clean energy to spare, like Paraguay, are also being courted by the industry, our investigation partner El Surti reports. In May, the US Secretary of State Marco Rubio proposed using Paraguay's energy surplus to power AI data centers. Paraguay owns the Itaipú Hydroelectric Plant, along with Brazil, and for now it produces more energy than it can use, so it sells its surpluses to Brazil and Argentina at below-market rates.

The courting of Paraguay comes as locals have begun to question the expansion of crypto-mining data centers — the use of power intensive compute to generate BitCoin and similar tokens on the blockchain. These facilities also produce serious noise pollution that impacts nearby communities.

"We've already suffered from the extractivism of our electricity, yielding it to Brazil and Argentina at miserable prices,” Mercedes Canese, former Vice Minister of Mines and Energy in Fernando Lugo's government told El Surti. “Now we also have crypto-mining and other digital services, which don't create jobs. The United States' interest is just another chapter in this extractive logic, which we're familiar with. It won't change the reality in Paraguay.”

Paraguay’s current Minister of Information and Communication Technologies, Gustavo Villate, dismissed these concerns and welcomed US interest that “positions us in an unprecedented way.” Villate told El Surti that the government has been working to close deals with data center companies.

Keep it secret

Despite the industry’s resistance to disclosure of its power and water consumption there is an awareness of the negative impacts. Internal documents obtained via the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s EDGAR public-access tool, show that one of the board of directors at one of industry’s leading actors, Digital Realty Trust, were asked by a shareholders group to “create a comprehensive policy articulating our company’s respect for and commitment to the human right to water.”

The board rejected this request, arguing that three out of four data centers in their portfolio do not use water for cooling, and Digital Realty, in response to written questions sent by this investigation via email, added that “shareholders overwhelmingly (~90%) voted against the shareholder's proposal at the 2025 Annual General Meeting (AGM)” and that ”42% of Digital Realty's global water use is sourced from recycled water supplies, minimizing the impact on local freshwater resources.” The same document found on EDGAR, however, shows that some of their facilities still use local resources and could impact communities.

“I’ve spent years trying to break down [the data center industry’s] financial records,” Max Schultze, director of the European thinktank Leitmotiv, told this investigation. “But [they] don’t break down where they pay taxes at all. They don’t even break down revenue per country... We have yet to see a cloud provider release the actual energy consumption or water consumption, or something like this, in a way that was either independently verified by a third party, or in a way that we can verify it independently.”

Schultze’s organization was among those who successfully lobbied the German government to enact a law forcing the industry to report water and energy consumption. However, “half of the data centers in Germany simply refused to report it,” he said. “They are all getting a fine of a hundred thousand euros for not reporting, but they don’t care about a hundred thousand euros.”

Tech Policy Press, the US partner in this investigation, asked environmental and consumer advocates how much information they could access on national data center projects. Most of them said it can be very difficult to get details, especially before the projects’ approval.

This asymmetry is exacerbated by the widespread use of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) signed by data center companies and local governments. “It’s very difficult with the NDAs, prior to them actually being approved, to know what is going to be in the facility,” Julie Bolthouse, director of land use at the nonprofit Piedmont Environmental Council told Tech Policy Press. “We don’t know how much water they are going to use, we don’t know what kinds of emissions, and we don’t know how much electricity they will need or what type of service they will require,” she said. “So basically we gather information after the fact.”

Free Press, a US nonprofit that monitors media and tech, has been tracking efforts to pass meaningful transparency laws. “A lot of companies release data in aggregate, which makes it difficult for folks in communities to understand what the specific impact will be,” said Jenna Ruddock, the organization’s advocacy director. “It’s important to pass those laws to make more information available earlier in the process, before the permitting and development is underway, when it is too late for the communities to have their say.”

This opacity also allows the data center industry to make promises about job creation and return on investment with little evidence or oversight.

Schultze said the industry’s “press releases work to make politicians believe that we need to digitize every country in the world, and that the only way to do it is with their infrastructure. But none of that is true.”

He points to a study his organization provided to the German government that showed that a data center building, on average, creates three jobs per megawatt used. By comparison, BASF, a large chemical company in Germany, uses 200 megawatts and creates 50,000 direct jobs. “What most cloud providers claim is that they are going to create millions of indirect jobs,” said Schultze. “No other industry gets away with that.”

Heleniza Campos, an expert in urban planning and a professor of urbanism at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) in Brazil, has been following the construction of a large-scale data center in Eldorado do Sul—a municipality where 90% of the territory was flooded in 2024—and studying other similar projects. She points out that new data centers are being proposed in cities lacking public resources, which “will accept anything, just for the money.”

“We need to understand that cost and figure out how to deal with it in a way that doesn’t harm the places where [the data center] is going to be built,” she told Agência Pública.

Keep good allies

Many Latin American countries have resources that data center companies want: cheap electricity, lax regulations and a willingness by governments to accept the promise that the AI race will bring a huge return on investment and lead to job creation. This investigation found that the relationship between technology companies and governments is complex and opaque. In some instances, governments desperate for foreign investment are working to attract data center companies, in others it’s the companies striving to convince governments and parliamentarians to let them build more facilities.

In Chile the government, led by President Gabriel Boric, has been one of the most eager in the region to bring in these companies and it has enacted a national Data Center Plan called PDATA. Chile’s pitch is simple: the country is politically and economically stable, is committed to investing in technology and to facilitating investments in the sector, particularly by easing bureaucracy and weakening the environmental licensing process. PDATA, launched last December, includes clarifying regulations for data center companies.

But PDATA did not come about in isolation from the data center lobby. During its framing, the Asociación Chilena de Data Centers, that includes the industry’s main players, such as Ascenty, EdgeConnex, Equinix, Google, OData, Scala, Nexstream, the specialized news outlet Data Center Dynamics (DCD), and real estate companies was created. The association has argued against a bill proposed by the government to regulate AI, claiming that it limits innovation and contradicts the National Data Center Plan.

Amazon has not joined this alliance, but lobbyists for Amazon and AWS have met at least 350 times with public officials, according to Chile’s public lobbying records. The same register shows Aisén Etcheverry, who was Minister of Science and Technology until recently, met with executives from Google, AWS, NVIDIA, Equinix and Meta.

In Brazil, industry groups have also influenced new regulations. Last year, the discussion of an AI bill was postponed several times due to industry lobbying. One of the reasons for that, sources told Agência Pública and ICL Notícias, was that the National Confederation of Industry (CNI) joined forces to encourage the creation of a data center hub. This hub would “generate employment and a fertile ecosystem for Brazilian industry,” CNI’s lawyer, Christina Aires, claimed in a private meeting.

In response to this investigation, the CNI said that it has been “in dialogue with members of Parliament and relevant economic sectors” about the bill that would regulate AI, but also clarified that the bill’s article about data centers “is not part of CNI’s proposals for the bill,” as this issue “requires a structured policy.”

The Confederation also defended data centers as an “essential part of digital infrastructure,” necessary “to make Brazil competitive in the global large-scale data production market.”

The CNI added that “the creation [of data centers] promises to have ample effects on employment and education” and quoted a 2023 report commissioned by the Data Center Coalition (DCC), a data center industry group in the United States.

The version of the bill approved by the Senate last December encouraged more “sustainable" data centers for AI systems. On the day the bill was approved, there were 16 Big Tech lobbyists in the Senate’s plenary, according to Carla Egydio, a lobbyist for small media. Agência Pública's reporter overheard Eduardo Gomes, the rapporteur of the bill, state his dissatisfaction with the pressure from the industry: “Out of 10 requests [made by the industry], nine are met... The next day they fill the newspaper [complaining] about what was left out.”

After being contacted by this investigation, Senator Gomes’s press team said that “parliamentary activity is made up of a great number of meetings, debates and intense negotiations. Pressures and counter-pressures from all parties involved are normal.”

The bill is now being discussed in the Chamber of Deputies, headed by the deputy Luísa Canziani, according to sources close to the process. Canziani’s father was previously involved in an opaque deal with Google while Secretary of State of Paraná.

On June 27, 2024, Conselho Digital, a lobby group that represents Amazon, Google and Meta, organized a brunch in Brasília to which representatives of senators and parties of all political currents were invited. The organizers said that “participants jointly analyzed the text, highlighting the progress made and possible alterations to be concluded.

Some officials are not waiting to be lobbied. In April this year, Brazil’s minister of finance, Fernando Haddad, went to Silicon Valley to present a new version of the National Data Center Policy to Big Tech representatives. He shared plans to give tax exemptions for investments in data centers. Núcleo reported that, when asked to share the text with civil society, the government refused.

The government of Nayib Bukele in El Salvador is also keen on attracting data centers and approved a reform to widen the kinds of activities companies can do in tax-exempted zones known as ‘zonas francas’. The Salvadoran government also approved new laws, including the Law for Innovation Promotion, the Law for AI Promotion and the General Law for the Digital Modernization of the State, which seek to turn the country into a tech hub. These laws offer tax benefits to data centers, in an effort to lure foreign investors.

Direct investment in El Salvador has been falling in recent years. The Chamber of Commerce’s president Jorge Hasbún said it is due to judicial insecurity brought on by a seemingly permanent state of exception declared by the government. However, some companies have arrived. In 2021, Ronald Jiménez, then CEO of Codisa, the Costa Rican company that owned the DataTrust data center in El Salvador until it was bought by IFX Networks, said in an interview that his company had made its way to the country because “El Salvador is a magnet for investment attraction.”

In the US, the industry has also used an association to influence the authorities, according to Tech Policy Press. Founded in 2019, the Data Center Coalition (DCC) is a member association that bills itself as “the voice of the data center industry.” Its members include Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Meta, as well as data center operators and related infrastructure service providers, including Stack Infrastructure, Digital Realty, Coreweave, and Oracle.

In recent months, the DCC’s President, Josh Levi, testified in a US Congressional hearing on the economics of AI and data center power consumption, penned a guest column in an Ohio newspaper proclaiming the economic benefits of data centers to the state, and made an appearance at a local Board of County Commissioners meeting in Calvert, Maryland, to discuss, among other things, the potential for local tax revenues from data centers. In Mississippi, Levi told a local newspaper that there is little downside to data center investment. “From my perspective, there aren't any negatives,” he said to Jackson’s Clarion Ledger.

In the state of Virginia, DCC formed a group called Virginia Connects to “educate and engage with Virginians about the benefits that data centers provide statewide and in local communities.” Last year, amid the introduction of various legislative proposals that could have negatively impacted the data center industry in the state, Virginia Connects sent “text messages and mailers touting the industry’s benefits,” according to the Prince William Times.

The group produced videos that it distributed via social media accounts on platforms including X, Facebook, and YouTube. “Virginia’s data centers are there for you, “a narrator promises in one of the videos. “Virginia’s data centers are essential to our national security and economic competitiveness,” says another, atop images of fighter jets, the Kremlin, Chinese leader Xi Jinping, and the Pentagon. According to Google’s Ads Transparency Center, on YouTube the videos were promoted by a Richmond-based public affairs agency, and despite the Virginia Connects account having under 200 subscribers, some of the videos it has posted have millions of views.

Keep it tight

Meanwhile, the data center industry has been consolidating, with a few large companies buying stakes in smaller ones to offer larger portfolios for single clients or co-location data centers, where multiple clients can rent “space”. But they are not only going after smaller tech companies. A closer examination of where the money is coming from that is driving billions of dollars into AI infrastructure, a picture of powerful private interests who stand to profit from the hype-driven expansion emerges. Despite its exceptionally speculative nature, the AI bet is pulling in money from institutional investors which would not be expected to be making high stakes gambles.

As much as a tech boom, the data center industry is a real estate business. The two largest data center players in Latin America are Digital Realty Trust and DigitalBridge, which together own or operate hundreds of data centers in this region.

Digital Realty Trust, a US-based multinational, claims to be the biggest company in the world in this sector, managing 308 data centers. In their 2024 financial statement they report to have a portfolio of 36 data centers in Latin America: 28 in Brazil, three in Mexico, three in Chile and two in Colombia. These numbers include both operating and planned sites.

In this same filing, they report 3936 employees around the world, but none in Latin America, and a total operating revenue of US$5.5 billion, only a slight growth from 2023, but of over 18% from 2022. Its net profit in 2024 was $561 million.

Digital Realty Trust is a prime example of why data center companies also operate as real estate investors. In their 2023 financial report they state they have chosen to be “treated as a real estate investment trust (a ‘REIT’) for federal income tax purposes,” which enables some benefits. As of December 31, 2024, they operated 54.9 million rentable square feet (about 5 million m2), “including approximately 8.9 million square feet (827 000 m2) of space under active development and 4.7 million square feet (437 000 m2) of space held for development”. The company reports that it does not own all the buildings in their portfolio, but leases many of them.

In 2018, Digital Realty announced on its website that it had completed the acquisition of a stake in Ascenty, a Brazilian data centre company founded in 2010 that operates these spaces in Brazil and other parts of Latin America. Digital Realty's Brazilian subsidiary, Stellar Participações Ltda, together with Brookfield Infrastructure (a subsidiary of Brookfield Asset Management), purchased 49% each, of Ascenty's shares for $1.8 billion. Chris Torto, the founder and CEO of Ascenty, kept 2%. It is through Ascenty that Digital Realty operates most of its data centers in Latin America, according to its own financial statements.

This partnership with Brookfield is indicative of the kind of money that is funding investment in data centers, much of it is coming from pension funds. Brookfield, headquartered in Canada, is one of the world’s largest owners and operators of infrastructure assets globally. According to the Center for International Corporate Tax Accountability and Research, “Brookfield has over US$800 billion in assets under management, much of which is workers’ deferred income from global public pension funds.” In many cases, this means the risk is widely distributed. If the data center industry indeed turns out to be in a bubble, should it burst, workers around the world would be shouldering the losses.

The other big player in Latin American data centers, DigitalBridge, also functions as a real estate company, in which many pensioners have invested their funds. DigitalBridge is the current name of a company formerly known as Colony Capital. In 2020, a subsidiary of Colony Capital, Digital Colony, bought UOL Diveo and created Scala Data Centers S.A. in Brazil. According to its website, Scala has 18 data centers in Latin America: 13 in Brazil, three in Chile, one in Colombia and one in Mexico.

Both DigitalBridge, which began as a technology infrastructure company, and Colony Capital, which was originally a real estate firm were founded by Thomas Barrack, a real estate magnate who is a close to Donald Trump and his current ambassador to Turkey. In 2019 Colony Capital bought DigitalBridge. Barrack was arrested in 2021 on federal charges of illegally lobbying Trump on behalf of the United Arab Emirates, and by that year, Colony Capital had rebranded to DigitalBridge. Like Digital Realty Trust, DigitalBridge is a real estate investment trust (REIT).

Keep it running

Energy companies, as well as real estate interests, are also driving the data center expansion. The AI boom is reversing years of declining power consumption and energy majors are among the interests stoking this speculation. Electricity companies stand to benefit from the construction of the new power stations that the industry is lobbying governments to finance in order to meet the demand created by the data centers that these same interests own.

The DataTrust data center in El Salvador, for example, is owned by the company IFX Networks, which also owns data centers in Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Honduras. IFX Networks is owned by another company, Ufinet, which in turn was bought by Enel Group, but then sold again in a transaction in which Enel retained a 19.5% stake. Enel is an Italian multinational that is the electricity provider in many cities in various Latin American countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico and Panama.

Brookfield, which as mentioned owns a 49%-stake in Ascenty, and therefore in most of data centers in Latin America, also owns ISAGEN’s, a formerly publicly-owned Colombian electricity company, which it bought in 2016. ISAGEN is in charge of six hydroelectric plants in Colombia, a country where most electricity comes from hydro power. ISAGEN also operates other 21 electrical power stations in the country.

The industry has enjoyed huge success in persuading governments across the world, and in Latin America, of the future benefits of AI infrastructure. Big Tech lobbyists, as in Brazil, are winning so often that they can complain about the rare carve outs that they did not receive. But the economic case for AI and in particular the hyperscalers’ approach to delivering unprecedented compute power, remains a “shot in the dark,” according to the Financial Times respected West Coast editor, Richard Waters.

Elsewhere warning voices from villagers whose taps run dry, to communities facing rolling blackouts to workers whose pension funds are being bet on a data center-driven bonanza are either fed industry propaganda or ignored. Even if data centers do turn out to be more than another investment bubble, it is far from clear how the wealth created will benefit the countries who are surrendering a rapidly growing share of their national resources. This kind of one-sided wealth creation has clear echoes in Latin America for those willing to listen for them.

“It’s just [data] storage and the exploitation of our natural resources.” Tania Rodríguez, leader of the Environmental and Communal Movement for Water and Territory (MOSACAT) told this investigation. Her group which emerged from the struggle against Google in Chile sees old forms of empire in the new technology: “It’s a new form of digital extractivism, we are being used by the Global North.”

Big Tech's Invisible Hand is a cross-border, collaborative journalistic investigation led by Brazilian news organization Agência Pública and the Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), together with Crikey (Australia), Cuestión Pública (Colombia), Daily Maverick (South Africa), El Diario AR (Argentina), El Surti (Paraguay), Factum (El Salvador), ICL (Brazil), Investigative Journalism Foundation - IJF (Canada), LaBot (Chile), LightHouse Reports (International), N+Focus (Mexico), Núcleo (Brazil), Primicias (Ecuador), Tech Policy Press (USA), and Tempo (Indonesia). Reporters Without Borders and the legal team El Veinte supported the project, and La Fábrica Memética designed the visual identity.

Authors