Mumbai’s Data Center Dreams Run on Coal and Inequality

Sushmita / Dec 2, 2025As India positions itself as a global data center hub, Mumbai’s rapid data center growth deepens energy pressure, fuels coal dependence, and exposes widening inequality.

The Environmental Impact of Data Centers in Vulnerable Ecosystems by Gloria Mendoza / Better Images of AI / CC by 4.0

In 2015, headlines declared that Panvel — a city on the outskirts of Mumbai and part of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region — would soon be slum-free. The then chairperson of the Panvel Municipal Corporation, Charushila Gharat, announced plans to rehabilitate slum dwellers and transform the town into an “international city” within two years.

Nearly a decade later, of the 3,500 families that were to be rehabilitated, thousands continue to live in precarious conditions. “We are on hunger strikes, but flats are still not allotted,” said Anita Telang Kolte, who works with out-of-school children in Panvel. “There is no electricity in their slums, and no proper water supply either. They fetch water from broken pipelines nearby. Many children end up begging to survive.”

The situation of the slum dwellers is in stark contrast with the other urban developments rapidly taking place in Mumbai , one of the most populous cities in the world. Mumbai now hosts data centers with a combined capacity of more than 4 GW by the first quarter of 2025, ranking third in the Asia Pacific region after Shanghai and Tokyo. As the number of data centers increases in the city and regulations are eased to facilitate their growth, they are likely to strain the city's scarce and precious resources, especially power and a hygienic water supply. Already, one in five Mumbaikars lives below the poverty line and the city is known as the city of maximum contrasts.

As artificial intelligence, cloud computing and streaming services expand worldwide, demand for data storage and processing has surged.

But this rapid growth has deep social and environmental implications. Data centers require round-the-clock, high-quality power. In a city already struggling to meet its own electricity demand, this expansion risks exacerbating inequality and locking India further into fossil fuel dependence, particularly coal.

Though the Panvel Municipal Corporation started the rehabilitation, it is far from complete. Tech Policy Press has written to the municipal corporation to ask for the status of rehabilitation.

Costs of electricity

Adani Electricity Mumbai Limited (AEML), one of the city’s major power distributors, projected a sharp rise in demand — from about 50 MW in FY 2022–23 to 638 MW by 2027. Of this increase, 354 MW is expected to come from proposed data centers alone.

To put this in perspective, 354 MW running continuously for a day could power 2.55 million urban households for a day, or 100,000 households for nearly 26 days. In rural contexts, this energy could serve 100,000 homes for more than 40 days, analysis by Tech Policy Press shows.

While showing these projections, AEML asked for the Dahanu power plant, which runs on coal, to aid round-the-clock electricity generation.

Mumbai’s power reality highlights the tension. The city’s peak demand reached close to 4500 MW this year, up by 900 MW compared to previous summer months. It generates roughly 1,800 MW locally through thermal plants — including Adani’s Dahanu plant and Tata Power’s Trombay plant — and some renewables, according to Mumbai power expert and veteran analyst, Ashok Pendse. The rest is imported from outside. “The rest of the electricity comes from outside. Bringing power from outside is the only option left to us,” Pendse told Tech Policy Press.

Yet many low-income neighborhoods supplied by AEML report frequent outages and sharply rising bills. In neighborhoods like Cheetah Camp in Trombay, some residents reported being billed for months they were away, or being charged for years-old dues.

“How can the electricity bill of a room and a kitchen be so high? I was traveling for work for a month and yet I received a bill of INR 13,000 [US$147],” said Nausheen Khan, a resident. “How could they charge us 15-year-old bills?” asked Ayyub Khan, a former ward member of the governing civic body, Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation.

Mumbai’s Cheetah camp area has been at the fringes of development. Residents of poor neighborhoods complain of escalating electricity bills even as data centers expand rapidly. Photo by author.

Cheetah camp, a neighborhood built after people were evicted from Janta colony for the said public purpose of building the Bhabha Atomic Research Center, itself requires several repairs. The roads are dilapidated and narrow, and sanitation isn’t well maintained.

In these neighborhoods, even as residents lament high power bills, electricity demand by data centers is increasing rapidly. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), data centers in India consumed around 2 TWh of electricity in 2014, accounting for 0.2% of national usage, and were expected to reach 3 TWh by 2020. Reality has moved much faster. Investment bank Jefferies estimates that consumption reached 6–9 TWh in 2023, with data center capacity projected to rise twelvefold to 17 GW by 2030.

This stark disparity underscores how India’s digital ambitions are being built on uneven and often unjust foundations. Tech Policy Press has requested comment from AEML.

Coal, communities and environmental fallout

The environmental consequences of this energy demand are playing out in areas like Dahanu, around 100 km from Mumbai. Farmers there are protesting proposed changes to the Dahanu thermal power plant, which supplies power to AEML. “The country doesn’t have a regulation mandating data centers to use power generated by renewable energy sources,” said Vibhuti Garg, South Asia director at Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

Of particular concern in Dahanu is the potential removal of the Flue Gas Desulphurization (FGD) unit, which curbs sulphur dioxide emissions.

“The fly ash [from the plant] is carried by the southwest winds blowing in the area to the chikoo crops and other trees. Earlier, the produce would be abundant, there wasn't any problem of pests, now all that has increased,” noted Vaibhav Vaze, a farmer from the area. “Even the bombil [Bombay duck] that fishermen and farm families used to dry to sell in the market, are becoming blackish in color,” he added. He pointed out that fly ash is carried in trucks and not liquified, leading to more pollution.

Dahanu is an ecologically sensitive and fragile area. The plant has been strongly criticized for contributing to the increasing pollution in the area. A study commissioned by the Dahanu Taluka Environment Welfare Association in 2022 showed the air to be polluted at hazardous, very unhealthy, and unhealthy levels of pollution.

“The FGD plant was installed 11 years after the plant started operations. Since the Supreme Court ordered the installation of the FGD, Adani has to go back to the SC if they want to cancel it,” said Pheroza Tafti, a resident and local activist from Dahanu. “Permissible sulphur dioxide levels here are already low. If the FGD is switched off, pollution will spiral.”

FGD systems reduce sulphur emissions that contribute to acid rain and respiratory damage. Studies show that emissions from the plant have damaged chikoo crops, dried flower stigma, and caused fungal infections, resulting in reduced yields and economic distress for farmers.

The Dahanu plant, a 500 MW facility acquired by Adani Power, uses a mix of domestic and imported coal. In July 2025, the Indian Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change issued a relaxation that exempted approximately 78% of thermal power plants from the mandatory installation of FGD systems.

Environmental experts argue that removing already-installed systems is both irrational and dangerous. “It is unclear what the purpose of removing an already installed plant is. Installing such plants incurs costs. But removal of an already installed plant is not helpful, and in fact may have adverse environmental as well as social impacts,” said Shripad Dharmadhikari, founder of Manthan Adhyayan Kendra, about the nature of power required for data centers.

Mumbai’s rise as a data center hub

Despite these constraints, Mumbai continues to attract data center investment. Its strong undersea cable connectivity to Europe, the Middle East, and Asia-Pacific, regulatory support, and saturated IT load in cities like Bengaluru position it as a gateway for global cloud and AI providers.

Mumbai and Panvel in Navi Mumbai have become prime locations for some of India’s largest data centers, including those by Nextra, Yotta, Larsen and Toubro (L&T), Sify Technologies, NTT, GDC, CTRLs, Reliance IDC, Tata Communications, Netmagic, Sify Rabale, making a total of 47 listed companies in just Mumbai, per datacentermap. These facilities are leased by global technology giants such as Amazon Web Services, Google, and Microsoft as colocation centers hosting multiple clients. Google is also constructing its first self-built data center in India in Panvel.

“Mumbai serves as an entry point for international platforms looking to scale across India and Southeast Asia,” said industry expert Yashasvi Rathore, head of corporate communications at Inductus Group, a tech consultancy firm in Delhi.

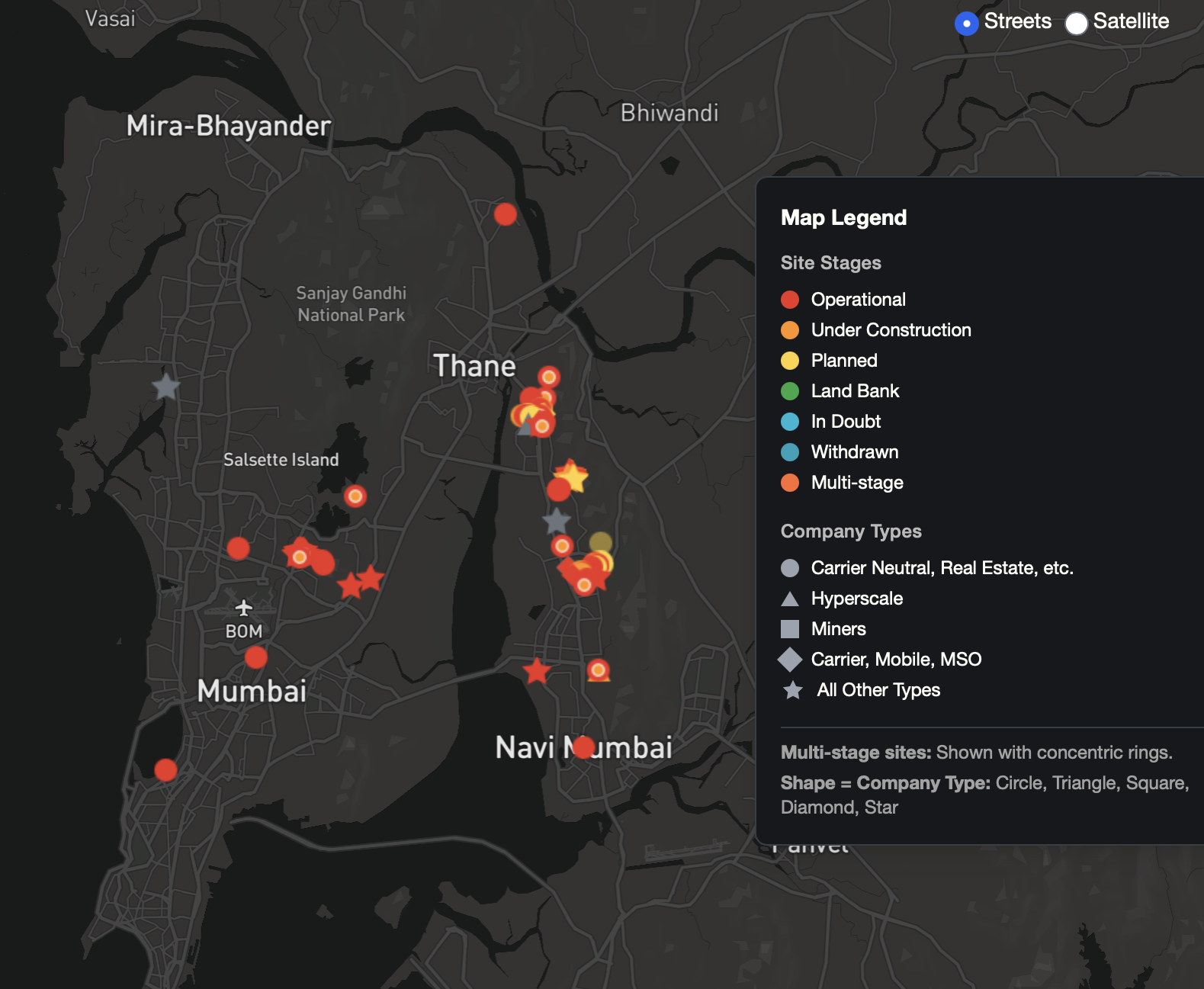

Data centers in Mumbai, Source: Baxtel

Competitive energy pricing and high connectivity make Mumbai attractive for global expansion strategies, but the benefits are unevenly distributed. The digital economy’s growth contrasts sharply with the lack of basic infrastructure in neighboring slums and informal settlements.

Even as these communities lack reliable electricity and water, the Maharashtra government has aggressively promoted data center development. It has classified data centers as essential services, offering substantial incentives under the 2023 Information Technology and Information Technology Enabled Services Policy of Maharashtra (IT & ITES). Incentives under the policy include earmarked land parcels, single-window approvals, relaxed zoning rules, even permitting construction in residential, green, and no-development zones, and eased Floor Space Index norms, allowing taller buildings on smaller plots. The data centers are exempt from the 21% electricity duty, which is billed monthly.

Data centers have to pay property tax at par with residential rates instead of commercial rates and are granted infrastructure status, along with various tax exemptions and subsidies for energy-efficient equipment. These measures create a favorable environment for rapid growth but raise concerns about how public resources and urban land are being prioritized, especially in a city grappling with housing and service shortages.

At the same time, regulations on coal mining and thermal power generation have been relaxed, for instance, in July 2025, when the government exempted 78% coal power plants from installing important mechanisms for pollution mitigation, reinforcing a development model that privileges industrial expansion, often at the cost of environmental and social safeguards.

These policies, paired with Mumbai’s connectivity advantages, help explain why the city remains a magnet for data infrastructure investment, even as it struggles to provide basic services to many of its residents.

The scenario in Mumbai reflects a broader global trend. Around the world, marginalized communities often bear the environmental costs of digital growth. In India, this imbalance is especially stark. Slum dwellers living without electricity and safe water share neighborhoods with hyperscale data centers that consume more power in a day than entire villages do in weeks.

Back in Panvel and Cheetah camp, the economic fruits of the data center explosion in India and the promises of digital supremacy they entail seem very off, almost impossibly distant.

This reporting was supported by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network as part of their “Dark Side of the Boom” reporting project on resource-intensive digital technology in Asia.

Authors