Scrutinizing the Many Faces of Political Deepfakes

Morgan Wack, Christina Walker, Alena Birrer, Kaylyn Jackson Schiff, Daniel Schiff, JP Messina / Nov 17, 2025

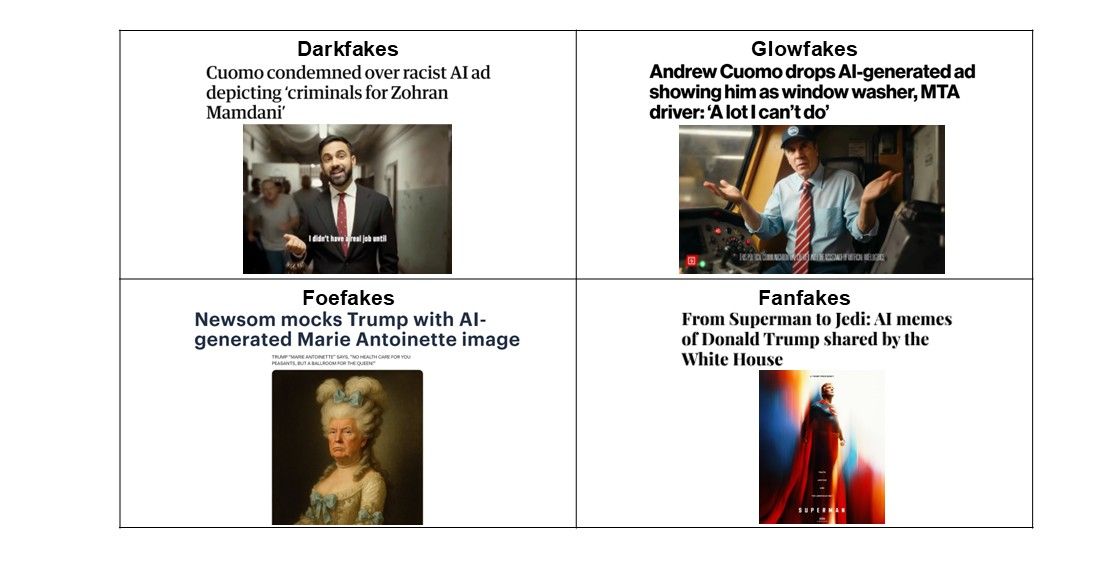

Examples of different types of political deepfakes provided by the authors.

When people hear the word “deepfake” in the context of politics, they most likely imagine something sinister. They might picture a politician's face convincingly placed onto someone else's body, a beloved representative framed for corruption, or even the fabrication of a scandalous tape aimed at sullying the reputation of an opponent. While malicious content certainly exists and poses genuine risks to democratic discourse, our research on political deepfakes tells a more nuanced story. Deceptive deepfakes represent only a fraction of the political deepfakes circulating online, even during election periods.

In a new working paper, we systematically analyze political deepfakes from the Political Deepfakes Incidents Database (PDID) compiled by Purdue University’s Governance and Responsible AI Lab (GRAIL), devoting particular attention to deepfakes surrounding the 2024 US presidential election. We find that the majority of political deepfakes do not intend to mislead viewers. Some satirize politicians through absurdist humor. Others advocate for causes or aim to educate viewers about deepfakes. Many others aim to boost rather than damage political candidates' reputations.

By failing to understand the full spectrum of political deepfakes, we may be setting ourselves up for ineffective responses and misguided policies. Recent research suggests that we need to get the language that we use to discuss deepfakes right, as the terms used to refer to synthetic content can affect individuals’ perceptions of risks and benefits.

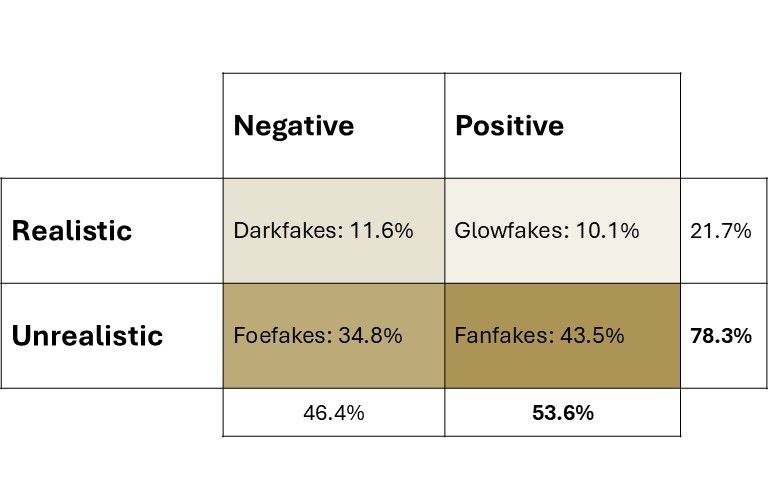

To address this blind spot, we developed a classification that categorizes political deepfakes along two key dimensions: whether they're realistic or unrealistic, and whether they portray their subject positively or negatively. This framework generates four distinct archetypal deepfakes that we label as darkfakes, glowfakes, foefakes, and fanfakes, each with its own characteristics, risks, and implications for democracy.

Figure 1: The four types of political deepfakes

The four types of political deepfakes

Darkfakes are realistic and negative. These are the paradigmatic deepfakes that dominate public and media discourse. They often involve impersonations designed to harm reputations by framing opponents as engaging in nefarious activities, including fabricated affairs, illegal dealings, or inflammatory statements. We selected the term “darkfakes” to allude to the type of nefarious content you might find on the dark web, reflecting their malicious intent. While rare, attention to this form of deepfake is not unwarranted, as they can pose a direct threat to individual reputations and can potentially sway voter perceptions through deliberate deception.

Glowfakes are realistic and positive. The term “glowfakes” stems from the colloquial fashion term “glow-up,” which references a transformative improvement to one's physical appearance. These deepfakes aim to glorify a candidate or party in a realistic way. They might show a politician delivering a powerful speech they never gave, or they might place a candidate in a heroic scenario that could plausibly have occurred but did not. Glowfakes serve as sophisticated propaganda tools, not through outright lies, but through strategic fabrication of positive moments.

Foefakes are unrealistic and negative. Unlike darkfakes, this form of content isn’t meant to deceive viewers by convincing them that something bad about a political opponent actually occurred. Instead, they depict opponents negatively using obviously fictional scenarios. Think of an image showing an opposition candidate as a blockbuster movie antagonist (e.g., Darth Vader) or in an absurdist nightmare scenario. The term “foefakes” reflects this adversarial nature while also acknowledging fictional framing. This common form of deepfake is often described by its creators as a form of political satire. While not deceptive in the traditional sense, foefakes may still shape public perceptions through compelling analogies and negative associations anchored to popular culture and memes.

Fanfakes are unrealistic and positive. Built around the concept of fan fiction, “fanfakes” celebrate favored politicians or parties as heroes in fabricated scenarios. A candidate might appear as a Marvel superhero, a revered historical figure, or a literal angel. Based on our analysis, fanfakes are surprisingly common. While not realistic, fanfakes may fuel the development of parasocial relationships between voters and politicians and can amplify enthusiasm within existing supporter bases.

Case study: the 2024 US presidential election

In order to better understand the prevalence of these different forms of deepfakes, we analyzed a sample of 70 political deepfakes from the 2024 US presidential election. Perhaps our most striking finding from this analysis is that “darkfakes” (realistic, negative portrayals) constituted only 11.6% of identified cases. “Glowfakes” (realistic, positive portrayals) were similarly scarce (10.1%). By contrast, the vast majority (78.3%) of deepfakes were unrealistic – either positively-oriented “fanfakes” (43.5%) or negatively-oriented “foefakes” (34.8%). Moreover, we found that newer tools were no more likely to be used to create darkfakes than traditional editing techniques, suggesting that generative-AI may be less useful for the development of purposefully deceptive content than previously thought.

Figure 2: Prevalence of different deepfakes in the 2024 US presidential election

The prevalence of unrealistic deepfakes (fanfakes and foefakes) challenges assumptions about viewer sophistication. Many researchers and policymakers have assumed that deepfakes only work if they are convincing, but our analysis suggests that AI-generated political content may operate through different mechanisms. Unrealistic deepfakes don't aim to succeed through deception, but may do so instead through emotional resonance, humor, cultural reference, and rhetorical framing. As an example, we witnessed multiple fanfakes invoking imagery of P’Nut the squirrel – an Instagram-famous squirrel euthanized by animal control, fueling calls against government overreach – to rally supporters around US President Donald Trump. A voter doesn't need to believe a candidate actually has the support of an adorable squirrel to find themselves positively associating with them.

Recent examples and policy implications

Our typology of political deepfakes is useful not only for analyzing the past, but also for understanding present and future uses of synthetic content for political purposes.

Recently, we have witnessed political officials from both major parties and across all levels of government – federal, state, and local – utilizing darkfakes, glowfakes, foefakes, and fanfakes to their advantage. From the New York City mayoral race, former New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s team has issued realistic deepfakes, both attempting to smear opponent Zohran Mamdani (darkfake) and boost his own reputation through appearing to do different jobs around NYC (glowfake). California Governor Gavin Newsom created a foefake to criticize Trump’s ballroom renovation during the government shutdown. Lastly, the White House has also shared fanfakes valorizing Trump as a Jedi or as Superman. Recent news reporting has picked up on these trends, revealing how Trump has used AI-generated images or videos to both attack opponents and rally supporters.

Figure 3: Recent examples of darkfakes, glowfakes, foefakes, and fanfakes

Our typology can help make sense of these patterns and can also inform associated policy efforts. First, it can provide a shared language (e.g., darkfakes and fanfakes) to discuss the diversity of deepfakes that we are witnessing. Second, it can enable greater attention to the varied means through which deepfakes can have an impact on the public (e.g., emotional manipulation versus deception), enabling nuanced risk assessment and tailored policy responses and platform governance efforts.

While the proliferation of political deepfakes has amplified concerns and deepened interest in developing informed policies and technological solutions, different types of deepfakes require different forms of mitigation. Darkfakes demand robust detection technologies and swift debunking mechanisms. Glowfakes require media literacy education about propaganda techniques. Foefakes raise questions about boundaries around satire and fair use. Fanfakes prompt considerations of how digital culture shapes political participation.

A blanket approach to “fighting deepfakes” risks treating satirical content the same as malicious attacks by foreign actors. These types of category errors waste resources while potentially infringing on legitimate political expression. At the same time, risks associated with unrealistic AI-generated content (i.e., foefakes and fanfakes) should be further explored.

As for future research on deepfakes, we hope that our typology is similarly useful. Studies that do not distinguish between types when attempting to measure nebulous concepts like “impact” and “efficacy” may generate misleading results and uninformative policy recommendations. Darkfakes and fanfakes may have completely different effects on voter behavior and should be measured separately. Future research on the disparate effects of these different forms of content may show how aggregating across types may obscure more than it reveals.

What comes next

As generative AI tools become increasingly sophisticated and accessible, the landscape of political deepfakes will only grow more complex. In turn, we need to improve our collective understanding of what we're seeing online.

Our typology attempts to address this challenge. It acknowledges both the risks and the creative potential of AI-generated political content and helps us to ask not only questions like “Is this real?” or “Do people believe this is real?” but also “What is this attempting to do, who created it, and how might it influence viewers?”

Democracy thrives on informed discourse. As we navigate this new era of synthetic media, public conversations about deepfakes must reflect the full spectrum of uses of generative AI tools. Only then can we develop proportionate, effective responses that protect democracy without stifling legitimate political expression.

Authors