Unlocking Innovation: Why Federal Procurement Should Embrace Open Source

Eunice Mercado-Lara, Shannon Dosemagen, Alison Parker / May 23, 2025

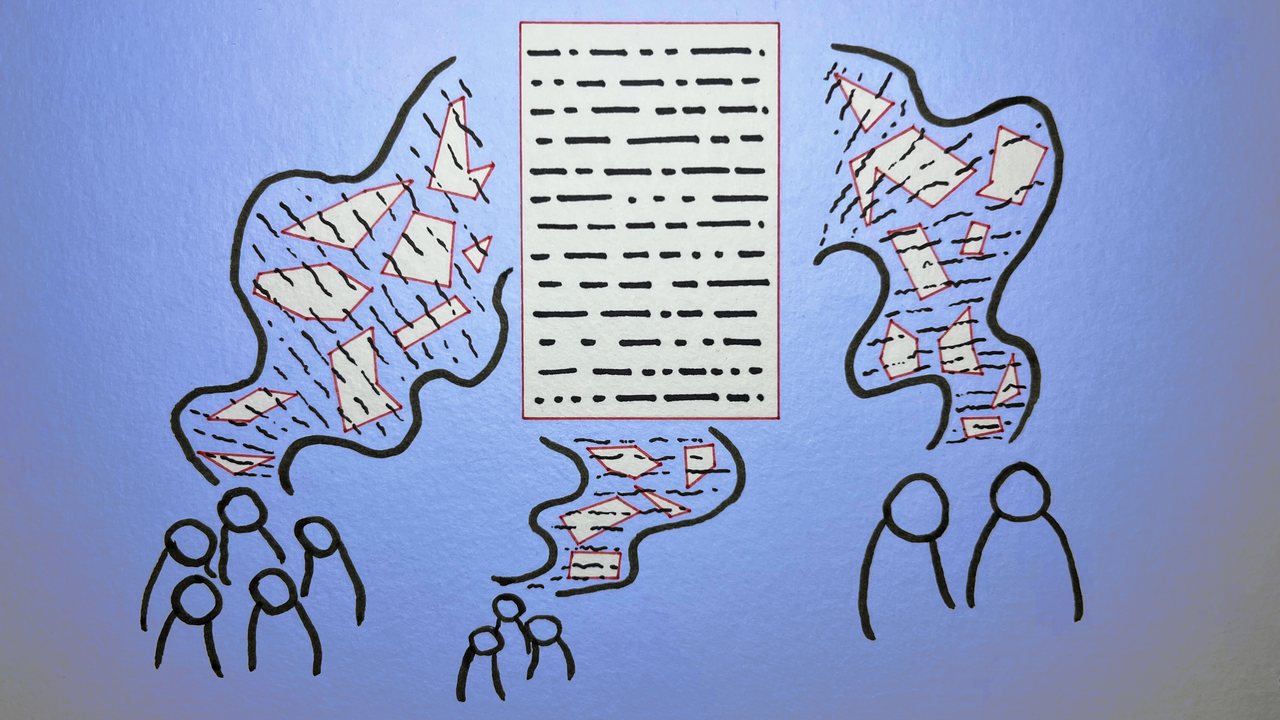

Yasmine Boudiaf & LOTI / Better Images of AI / Data Processing / CC-BY 4.0

When the US government spends $75.1bn annually on technology, it does more than purchase tools; it decides who shapes the infrastructure of democracy. Procurement choices shape the landscape of science by exerting control over who can participate in the market of science and technology products and services. At the same time, the procurement process shapes the landscape of federal science by determining what tools and technology are available.

This administration’s April 15 Executive Order (EO) on federal procurement promises to reduce the barriers for small businesses who want to participate in federal contracting by reducing bureaucratic hurdles and creating a more competitive environment. It is clear the EO was not written with open-source in mind, yet its silence on open-source solutions risks cementing a detrimental status quo: a scientific and technological ecosystem restrained by and only accessible to a handful of vendors. Without a vision to broaden who can participate in federal procurement and who will benefit from it, the federal government will keep overpaying for outdated systems, stifle competition, and surrender leadership in critical fields like AI and healthcare.

Consider a common scenario. Small firms developing open-source diagnostic devices, at half the cost of proprietary machines, bid for a government contract. They collide with a system designed for incumbents: labyrinthine compliance requirements, unclear scoring metrics, and a preference for vendors offering “proven” systems. Or, they simply do not attempt to participate in the procurement process, knowing they do not have the capacity to compete. The result? Taxpayers fund locked-in technologies, innovative startups are shut out of opportunities to receive public investment, and the government misses an opportunity to improve outcomes in public health. This is not inefficiency; it is a form of institutional capture.

The EO’s streamlining of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) is a necessary step in the right direction. But an overhaul of procedure alone is not enough to fully dismantle barriers to new models for technological innovation. In addition to flexibility and help for small businesses, agencies need a vision for a new approach to procurement that benefits agency missions and innovative vendors alike. The procurement system should add value to both the market of tools and technology and small businesses engaged in scientific entrepreneurship. One answer is open-source.

As participants in and researchers of open-source teams and projects, we have seen firsthand the financial and logistical hurdles facing open-source innovators. Open-source developers include scientists participating in technology transfer, personally advancing their research from the lab to practical application. During a 2023 roundtable on open scientific hardware, participants detailed how federal procurement systems overwhelmingly favor “known entities” and engage with vendors through complex, opaque, and time-intensive processes, shutting out smaller, agile competitors. The federal procurement system dictates the terms of this engagement, creating a range of difficulties for scientist-entrepreneurs when attempting to sell their innovations to the government.

Many federal IT systems still rely on outdated software that is “locked-in” to a specific vendor (e.g., Oracle databases, SAP ERP). To give the reader an idea of what we are talking about, until 2019, the US nuclear arsenal relied on computers that used floppy disks; to this day, the national airspace system still uses them. Typically, these service providers have long-term contracts and are likely to prioritize profit over progress, delivering minimal upgrades during the contract period. Such reliance creates more than technical debt; it concentrates power. When a few vendors dominate labs, hospitals, or defense systems, they dictate the pace and direction of innovation. A clear option to address these costly vendor lock-ins is to adopt modern open-source alternatives.

Open-source tools and solutions, publicly accessible, modifiable, and free from proprietary constraints, can cut costs, reduce dependency on single vendors, and help reclaim leadership in scientific R&D. However, this is only possible if procurement rules are designed to welcome them. Take the Department of Defense’s 2022 shift to Kubernetes, an open-source platform for managing cloud services. By adopting it, the DOD improved the resiliency of its development security operations infrastructure and achieved a more sustainable, adaptable, and secure system.

Unlike proprietary systems, Kubernetes lets agencies own their infrastructure, share upgrades across borders, and avoid being held hostage by a vendor’s roadmap. Similarly, the European Center for Nuclear Research (CERN), a highly complex organization, exemplifies the effectiveness of an open approach. In its need for tailored and agile solutions, the procurement model prioritizes collaboration, avoids monopolies, and ensures long-term sustainability. If US agencies follow suit, lowering barriers for open-source vendors, they could save costs, boost small businesses, and reclaim leadership in R&D.

From lab equipment to software, open-source solutions offer cost-effective, customizable options that are free from vendor lock-in. To reclaim democratic agency, the US must revamp its procurement processes and prioritize open-source.

Three essential principles can facilitate this shift:

- Consider open-source alternatives in federal contracting. Agencies should be empowered to evaluate open-source solutions through requirements for comprehensive cost-benefit analyses comparing them with proprietary options, with clear justification required for final selections. The procurement process should further support this shift by mandating agile software development methodologies in IT solicitations, requiring demos of the products instead of memos, and emphasizing iterative delivery and user-centered design. Together, these reforms would create a procurement environment where open-source solutions can compete on their merits while reducing vendor lock-in and increasing technical flexibility.

- Encourage modularity over monoliths. Monolithic proprietary contracts lock agencies into paying premium prices for systems that become more obsolete with each passing year. Rather than single vendor ecosystems, aspiring to modular frameworks in government contracting where agencies can plug in new tools, from e-health records to tax filing, without overhauling entire systems, offers an alternative option to "replace all or nothing."

- Lower barriers for small innovators. Procurement rules often favor established vendors and exclude smaller companies. Public bids typically require costly financial assurances, such as multi-million-dollar bonding capacity, which many startups don't have. They also impose arbitrary experience thresholds, like out-of-scope requirements for services only incumbent providers can support, effectively shutting out newcomers. These barriers stem from a system focused on bureaucratic risk aversion rather than innovation. Simplifying requirements to focus on outcomes, such as a vendor’s ability to identify, monitor, or address specific problems or needs, rather than requiring them to respond to solutions created under specific proprietary software, could open doors for newcomers. Additionally, providing feedback on rejected bids would help startups learn and improve. The goal is to assess vendors based on their contributions rather than their ability to navigate rigid processes.

The EO's four-year sunset clause for outdated regulations is an opportunity. Rethinking the procurement system should include replacing proprietary favoritism with policies that welcome and support open-source competition, from startups and small businesses alike.But without targeted guidance, agencies may default to old habits, clinging to familiar vendors. To avoid this, the administration could start by increasing awareness among agencies and training procurement officials on the value of open-source solutions. It could launch pilot programs to demonstrate cost and efficiency benefits. Finally, it could rewrite rigid rules that currently shut out small innovators.

Procurement is a battleground for democracy itself. Closed systems benefit certain kinds of vendors but impoverish public capacity; open-source tools redistribute power to citizens, scientists, and startups. Reforming procurement to address the myriad proprietary lock-ins can help to revitalize the connection between government and small, open-source businesses. This Administration claims to prioritize small businesses and competition. To prove it, they must wield procurement not as a blunt instrument, but as a scalpel, slicing through vendor lock-in and suturing a new ecosystem where public interest, not private profit, dictates progress.

Authors