US Critical Mineral Aggression Abroad Connected to Data Center Fights at Home

Hannah Lipstein, Tamara Kneese / Feb 19, 2026

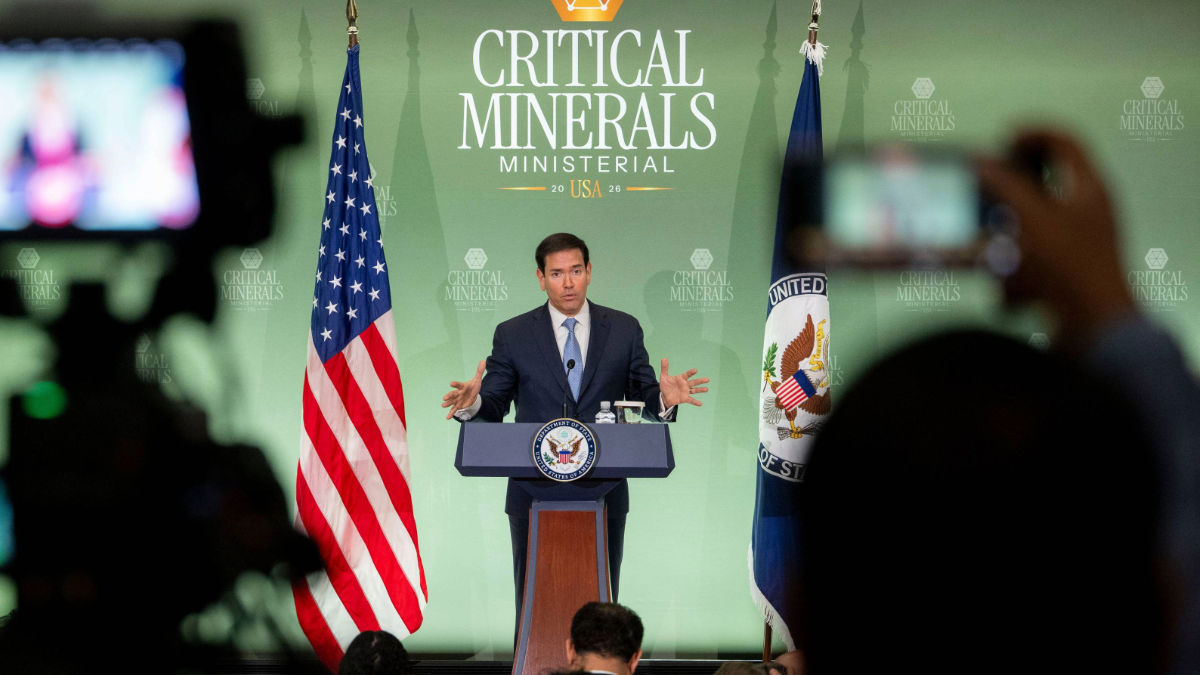

Secretary of State Marco Rubio speaks at a news conference during the Critical Minerals Ministerial meeting at the State Department, Wednesday, Feb. 4, 2026 in Washington. (AP Photo/Kevin Wolf)

Even as the Trump administration brazenly undermines other nations’ sovereignty in the pursuit of the critical minerals necessary to fuel the AI infrastructure boom, the data center fight in communities across the United States has not left the headlines. These two phenomena are not independent of each other: America’s industrial policy and practice are increasingly shaped by the massive resource demands of the “AI revolution.” The data centers themselves, the chips that reside within them, and the energy infrastructure needed to power them are all entangled in material and political supply chains that link the communities on the frontlines of data center buildout to those on the frontlines of resource mining and refining. These connections matter, both because they reveal the full environmental impact and geopolitical complexities of AI’s infrastructures and because they open avenues for new forms of solidarity.

As recent moves by the US to claim natural resources in Venezuela and Greenland demonstrate, the colonial history of the Global North’s plunder of the Global South is seeing a reprise. Simultaneously, this pattern is being complicated by recent moves to onshore more critical mineral production, in part to power AI but also to manufacture the batteries and parts necessary for a green energy transition. These developments juxtapose the hyperlocal and the global, but also increasingly link them, as raw mineral extraction crops up on domestic shores. For instance, Nevadans are currently confronting the massive Thacker Pass mine, which is slated to produce 40,000 metric tons of lithium carbonate for 800,000 electric vehicles in its first phase, while Arizonans are encountering the staggering consumption and pollution from the country’s first TSMC semiconductor chip factory.

In our ongoing study of data centers, a recurring factor that shapes the analysis is the data center’s particular geographic and sociopolitical context. The actual political relevance of each site is necessarily informed by local conditions; yet, data centers cannot be understood, as a phenomenon, when fully abstracted from their essentially global context. It is much easier to quantify and qualify the immediate, case-by-case impacts of a set of data centers on the ground, but grasping the full picture of data center impacts requires contending with the entangled, ever-changing, and fundamentally unseeable global flows of materials, capital, and power—each with their own implications for communities, ecosystems, and the larger climate crisis.

‘AI ecosystems’ meet actual ecosystems

If the 20th century ran on oil and steel, the 21st century runs on compute and the minerals that feed it. This historic declaration hails a new economic security consensus ensuring aligned partners build the AI ecosystem of tomorrow—from energy and critical minerals to high-end manufacturing and models. — Jacob Helberg, Under Secretary for Economic Affairs at the State Department, in the Pax Silica Declaration.

A vision of a state running on technology can be easily mythologized in a State Department proclamation, but an imagined “AI ecosystem” quickly collides with actual ecosystems and geopolitics. Tech Policy Press recently analyzed how this “Pax Silica" pact—an American-led AI supply-chain alliance between “trusted” nations—more or less confirms the motivations behind the US’s increasingly-plausible blustering of its Greenland grab. But as Data & Society affiliate researcher Zane Griffin Talley Cooper shows, this imperialism is one that ignores the actual inhabitants and topographies of Greenland for a fantasy of AI frontiers and crypto-enabled network states that emerge from mineral riches. These facts on the ground challenge American material ambitions, creating friction that elevates the risk of deadly military escalations like those deployed in Venezuela.

Still, as the US maneuvers for control overseas, it is also expanding domestic production as a means of reducing foreign reliance. In doing so, it is bringing the unwelcome secondary effects home, too. In October, the US purchased a stake in Lithium Americas, a company developing a major lithium mine in Thacker Pass, Nevada. Indigenous groups, community members, and environmentalists have spent years sustaining a strong resistance to the project, which will generate irreparable harm to the local environment. Beyond these injuries, the ACLU and Human Rights Watch recently concluded that the mine’s permitting process violated the rights of local tribes—a grim echo of the patterns of exploitation shadowing the history of industrial development here and abroad.

In addition to mining, onshoring also includes manufacturing; Arizona is now contesting two major semiconductor packaging plants, the onsite environmental impacts of which practically dwarf those of data centers. And these trends predate the current administration: Judith Barish, Coalition Director of CHIPS Communities United, warned in 2024 of the “massive subsidies involving taxpayer dollars that are going to an industry with a track record of exploiting workers and damaging the environment.” These concerns have only become more urgent as Trump kickstarts “Project Vault,” a $12 billion domestic critical minerals stockpile intended to shift the US away from dependence on China.

The resource-grab makes sense in light of the sheer magnitude of physical inputs (and waste products) constituting the “AI ecosystem.” Data centers, visible as they are, are just one piece of the sprawling apparatus that links Greenland to Venezuela to Chile to Colleton County, South Carolina. Beyond the buildings themselves and computing servers, data centers are inseparable from the electrical and water infrastructure needed to operate, and are steadily becoming one and the same with the nation’s energy infrastructure: developers are bypassing the long queue to connect to the public grid and simply bringing their own portable gas plants. Each of these elements—solar farms and gas plants, batteries for energy storage, diesel backup generators, transmission lines—is its own tangled product of a convoluted and self-reinforcing chain of material extraction, refinement, manufacture, and transportation, many times over.

As University of California, Los Angeles associate professor Miriam Posner’s work on supply chain management software makes clear, supply chains are notoriously opaque, even to corporations that might not be aware of how their vendors source materials, and fluid, as various political and ecological crises shift the sites of resource hubs. And simply mapping the observable movement of materials often fails to capture the localized impacts on labor and resources. Scholars like Ana Valdivia use ethnography to attach embodied and environmental repercussions to the AI supply chain visuals that can feel so abstract and remote. Projects like “Geographies of Digital Wasting” capture the stories behind the full digital supply chain—or supply webs, as the project suggests—from extraction to disposal and e-waste afterlives, in specific geographic locations. Meanwhile, new endeavors such as the AI Supply Chain Impact Framework attempt to create accountability frameworks for such complex sets of relations.

It is not just the fact of Big Tech’s domineering in global supply chains at issue, but the far-reaching implications of what is sacrificed to feed their machines. The battery industry provides a telling example. Political scientist Thea Riofrancos’ latest book, Extraction: The Frontiers of Green Capitalism, builds upon her scholarship on resource nationalism in South America and its connection to green technology. From the setting of the lithium-rich salt flats in Chile’s Atacama desert, Extraction vividly illustrates the environmental toll of such ruinous mining in delicate ecosystems, while casting it against the geopolitical machinations that have shaped the industry across decades and continents. Exposed to shocks from political upheaval, characterized by corruption and regulatory failure, and resisted at each step by Indigenous communities and residents, lithium extraction is center stage in global markets. The mineral is indispensable to the most effective forms of battery storage, and thus plays a critical role in green technologies like electric vehicles and renewable energy. Batteries are also essential for data centers, which require a constant, uninterrupted power supply: Google boasts that it has installed 100 million battery cells exclusively in its data centers.

Developing enough battery storage to meet the needs of data centers and to get the rest of our economy off of fossil fuels is a zero-sum proposition. Renewables are not an inexhaustible panacea, as the shrinking salt flats in the Atacama remind us. These harms are an unavoidable problem that demands a reckoning with much more macro questions of how we allocate resources on a finite planet. Should we prioritize these minerals for electrifying homes and cities, or for keeping AI products online? Or will we simply scale up the frenzy of extraction, transporting ecological havoc to new frontlines?

Expanding avenues of resistance

Ultimately, data centers and the resource extraction they demand are part of the same supply chain—and therefore the same fight. From a strategic perspective, in efforts to resist data centers, we need to be principled about including the supply chain as part of our political analysis as we raise the profile of this issue. Data center apparatuses are vehicles of corporate and state power, up and down the line; foregrounding the supply chain as we build our movements exposes its stakes.

Doing so also opens the aperture of resistance. Currently, the onslaught of data center buildout has necessitated the rapid establishment of networks of response across disparate geographies. As soon as a project comes to town, there are activists around the country ready to spring into action to lend their expertise; in turn, our tactics are evolving. Coordinating our campaigns with those in the fight for sustainable mining and manufacturing, here and abroad, would further diversify our strategy. Protests at mine sites, for example, have proven effective in delaying or even halting projects that fail to respond to communities’ needs. While data center developers can simply move on to the next location if their operations become ensnared in public outcry and legal challenges, mining operations do not benefit from such mobility. Mine sites are often selected after years of careful exploration and planning, and, critically, they are tied to the fixity of the minerals themselves. In effect, by targeting the resource supply itself and the end product, we can create chokepoints both upstream and downstream in AI instantiation.

Given the rich legacy of resistance movements against extractive industries abroad, our most important mentors and allies may be found in coalitions operating around the world. As a critical minerals and AI workshop at the Institute for Advanced Study made evident, the Global South is indispensable to AI development, even as industries move to domestic shores, and thus positioned to negotiate with the Global North. There is a dire need for local governance models that buck external time pressures and priorities while coordinating across continents.

This is not an indiscriminately refusalist position: mounting a principled opposition to the resource grab for AI allows us to fight for just distributions of green technologies. Our world urgently needs to phase out fossil fuels—but this cannot be done by endlessly rearranging environmental sacrifice zones around the globe. Seeing data centers’ full footprint brings into sharp relief Big Tech’s role in driving the dangerous new wave of resource imperialism and demands to meet corporate appetites at the expense of climate progress. Data center harms operate on so many scales, with shifting degrees of visibility: they endanger clean air and water for those in the backyards of the facilities themselves, those on the banks of mines far abroad, and for those of us still waiting on the ever-elusive green transition. The wealthiest companies in the world do not have the right to expropriate our carbon-free future. Rather, we have the mandate to ensure that the world’s resources go toward the public good.

Authors