‘Big Cloud’ is Building Power via Pervasive Investments

Nathan Kim, David Gray Widder / Aug 12, 2025

Nadia Piet + AIxDESIGN & Archival Images of AI / Better Images of AI / Cloud Computing / CC-BY 4.0

Criticism of Big Tech monopoly power from journalists, regulators, and scholars often focuses on the largest mergers and the highest-profile anticompetitive practices. The remedies trial in the Google Search antitrust case is a good example, as is Microsoft’s much-criticized acquisition of Activision Blizzard, or the monopoly case Meta is embroiled in. Critiques are particularly pointed against the monopoly power held by the subset of Big Tech firms which are the large cloud infrastructure providers. Just three companies comprise which “Big Cloud” — Microsoft, Amazon, and Google — control two thirds of the cloud computing market, thereby controlling services that millions of businesses and governments across the globe rely on. Big Cloud has come under fire for anticompetitive practices across the globe, and most relevant to our focus here, Microsoft faced particular scrutiny for its eye popping $14 billion investment in OpenAI.

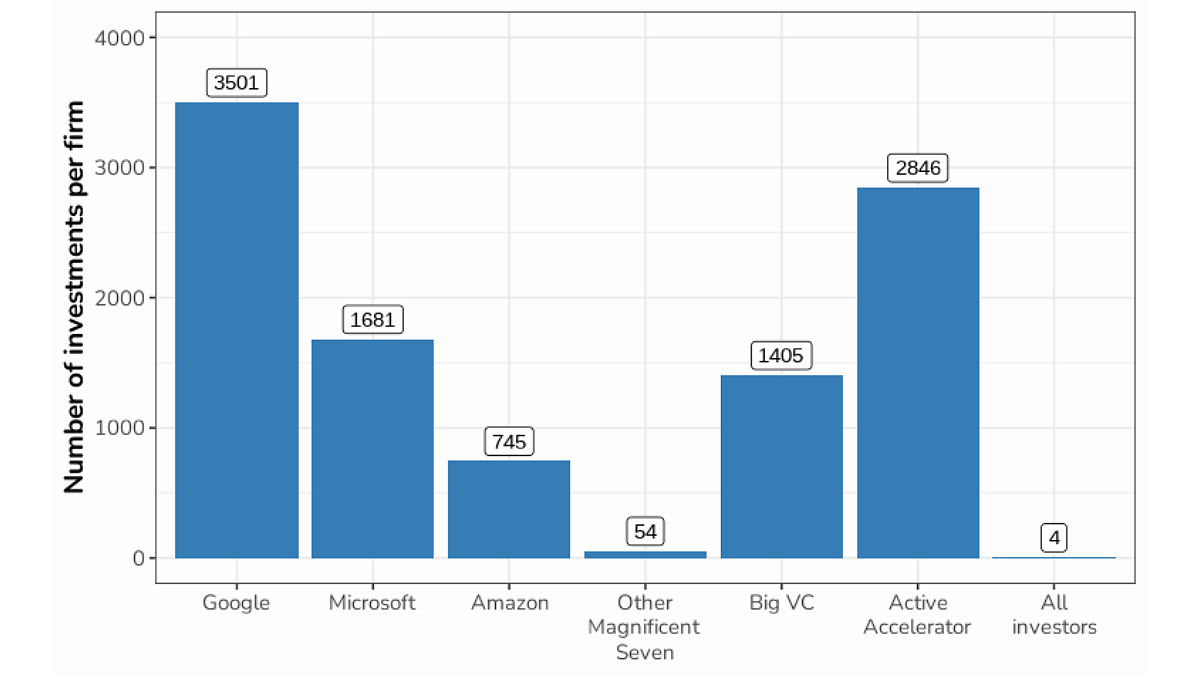

But while $14 billion investments grab headlines, our new report shines light on a distributed, far less visible, and cumulative form of dependence garnered via investment. We analyze investment database Crunchbase, which collates records of investment from a variety of sources, and find that Big Cloud invests in over a hundred times more deals than other Big Tech companies in the "Magnificent Seven" (Apple, Meta, Tesla, and Nvidia). Moreover, Big Cloud has participated in a staggering $250 billion in total funding dispersed throughout the startup ecosystem. Our research suggests these investments comprise a massive, strategic effort to bend the technology ecosystem towards Big Cloud’s interests.

Big Cloud invests much more often than other important investors. Source.

As shown in the graph above, the scale of Big Cloud’s investments are very much unlike other Big Tech company investments, and similar in scale to startup accelerators and venture capital investors. But traditional startup accelerators make many small deals to early-stage startups, spreading money out in search of rare thousand-fold returns, while providing mentorship and connections. Traditional VCs make larger, but fewer, deals than accelerators, and are often focused on repeated deals in ever-larger rounds. Both are focused on making, above all, a huge payoff. But as we explore in the report, Big Cloud makes both large deals and many deals.

Big Cloud invests in pursuit of industry capture

So why does Big Cloud pursue this relatively unique investment strategy? Our analysis reveals that investments intensify other anticompetitive practices. We unpack their playbook — including accelerator programs, the pursuit of sole or lead investor roles, and the pursuit of a kind of vertical integration through investment — to show how Big Cloud companies ensnare early-stage startups across the entire tech industry into their proprietary ecosystems.

The playbook starts with each Big Cloud entity setting up accelerator programs, which are special funding vehicles that operate with cohorts of investment targets, typically prefer very early-stage startups, and provide them not only capital but also networking, office space, and — critically — compute credits. We found that Google, Microsoft, and Amazon each have strong affinities for investments through accelerators, with 52.9%, 59.7%, and 25.6% of their investments, respectively, issued through accelerator programs. In contrast, the other Big Tech companies we studied do not run accelerator programs at anywhere close to the same scale, or even at all.

Startups receiving investment are especially at risk of heavy financial dependence on their Big Cloud partner as their sole or lead investor. Big Cloud companies act as the sole investor for 53 to 57 percent of deals they participate in, and lead investor for 66 to 70 percent of deals. Other Big Tech companies aren’t as concerned with playing as significant of a role in each of their deals, and are the sole investor on an average of just 34 percent of investments and lead investor on 44 percent of investments. That significant influence exerted by Big Cloud investors, in tandem with other anticompetitive strategies like high egress fees and minimum spend contracts, locks startups receiving investment into Big Cloud’s ecosystems.

Cloud computing giants use these investments to exert influence over the entire tech industry, and especially over emerging (but yet unproven) technologies like AI. As our research shows, Big Cloud’s investments reach across the AI supply chain — into data providers, infrastructure layers, developer tooling, and application companies — acting as a form of “soft” vertical integration that escapes the kind of scrutiny more often directed towards vertically integrative acquisitions. Stipulations as part of investments reinforce Big Cloud’s AI edge: participation in some of Google’s accelerator programs requires an "AI-first" approach in addition to using Google Cloud Platforms. Amazon’s incentive structure multiplies for generative AI startups — offering $300,000 in credits for AI companies, three times as many credits as other kinds of startups, to steer them towards compute-heavy business strategies that are especially lucrative for the Big Cloud investor.

Big Cloud investment targets the global economy

The scale for this playbook is global. Our research finds that Big Cloud invests abroad at a pace and preference far outpacing Big Tech competitors. Big Cloud makes just over half of its investments abroad, with Google, Microsoft, and Amazon making 1,645, 1,001, and 322 investments abroad respectively. In contrast, Apple, Nvidia, Tesla, and Meta together only have made 80 investments abroad to date — any one of the Big Cloud companies easily invests more abroad than the next four tech giants combined.

Big Cloud invests abroad to seed influence in newer markets. Accelerator programs are particularly useful for this strategy, with Google making 79.5% of its non-US investments through accelerator programs, compared to just 26.8% of its US investments. Microsoft and Amazon follow similar trends. In domestic markets, Big Cloud’s influence already reaches a broad audience. Abroad, Big Cloud uses accelerators as instruments of soft control — expanding its footprint under the guise of startup support while locking in infrastructure dependence.

For recipient states, this translates to a slow erosion of digital sovereignty as national innovation systems are quietly tethered to the US-based cloud infrastructure, billing relationships, and technical roadmaps. As Big Cloud’s anticompetitive practices now appear to have full backing of the US government, our findings emphasize the importance of responses from both the Global South and the Global North in combating encroachment on digital sovereignty via investment. We join the broad chorus of voices advocating for digital sovereignty to prevent against US dominance, and especially encourage a broad approach to the sovereignty-focused frameworks to also include the financial infrastructure the AI supply chain may be built on. Any kind of “sovereign” AI with the independence that sovereignty frameworks call for can’t be built on US infrastructure backed by Big Cloud’s dollars.

Conclusion: acting against cloud investment capture

More broadly, our results emphasize the importance of structural separation, echoing many past calls. Dependence on Big Cloud is not just technical or infrastructural: it is also financial, as a source of investment. This then compounds the need for structural separation: Amazon, Google, and Microsoft must be compelled to split their cloud business from their other businesses that run on the cloud, so that they do not both provide infrastructure and compete with the customers and investees relying on that infrastructure.

Most importantly, instead of just scrutinizing the biggest deals, researchers and regulators must contend with the cumulative nature of these investments — as we have shown here. It is the industry-wide effect of thousands of deals, rather than any single investment, that allows Big Cloud to grow even bigger, constitutes a chokehold over national economies, and constrains the technological choices available to millions of people. Any one of these investments may be small and insignificant, but they cumulatively shape the startup and developer ecosystem in Big Cloud companies’ interest. As we scrutinize Big Cloud’s investments, we risk missing the forest for its tallest trees.

The full report, "How Big Cloud becomes Bigger: Scrutinizing Google, Microsoft, and Amazon's investments, can be accessed here.

Authors